Anthropologist Alena Lochmannová is a CU graduate and the author of Body behind Bars, a remarkable ethnological monograph examining tattoos and body modification in Czech prisons. Based on hundreds of interviews conducted over more than five years, her study casts light on a world most of us cannot imagine. Tattoos, the author says, not only map the prisoner’s journey but reveal the shape of their soul.

You yourself have and love tattoos (which you kept hidden from prisoners for the sake of this study). Do you remember the first time you saw a tattoo?

I first began noticing tattoos at an early age. I was surrounded by people who had tattoos but the first time I think I was four or five years old. As children we spent a lot of time at the local pond and there was a fisherman who was often there in the summer. He didn’t say much but we liked him and had a kind of natural respect for him. But my grandmother didn’t want him speaking to me and would always drag me away. She called him an “old criminal.” When I asked why, she pointed to his tattoo: a heart with initials on his hand that I think it had merged with other tattoos. I think a lot of people remember seeing tattoos for the first time and have a similar experience, regardless of age, place, or gender.

You took your initial fascination much further: you made tattoos the subject of extensive ethnological research.

The focus at the beginning was different and the result, now published, was something I couldn’t have imagined when I started. I visited jails because I was interested in the kinds of tattoos convicts had. I was interested in what partial symbols meant and wondered if any symbolism had survived at all. Not only did I get the answers, but my ethnological study allowed me to uncover just how important body modification is in the “second life” of convicts. How non-verbal communication plays a role. I focused on what the convict’s body tells us about life behind bars, about the shape of his soul, and the extent to which a person’s identity is inscribed in their tattoos. That was the main focus.

You call it a transformation...

Yes, it is. The act of getting tattooed is a transformation and feeling physical pain is an important part of it. Tattoos can range in meaning from a declaration of status to signifying gender (regardless of whether you were born a biological male). Sometimes prisoners will tell you that a tattoo “means nothing.” But there is always some meta-communication potential simply because tattoos are not allowed in Czech prisons. The very act of getting an illegal tattoo behind bars, an act that is punishable by the authorities, sends a message. An illegal tattoo can not only complicate a convict’s time in jail, it can also jeopardise their chance of getting an early release. So behind bars, every tattoo in prison is important, even one that is only ornamental. At the same time, you have to perceive the person’s whole body: how they move or carry themselves, as well as where they fit in. You can have a very rigid code of tattoos and symbols, for example, when it comes to Russian-speaking inmates. There, you can’t just get any tattoo you like, especially if you haven’t merited it. The tattoo you can get within such a gang depends on your past and on your criminal career. There is a deep-rooted and traditional symbolism and a “correct” coding grid among Russian prisoners which is fascinating.

Yes, it is. The act of getting tattooed is a transformation and feeling physical pain is an important part of it. Tattoos can range in meaning from a declaration of status to signifying gender (regardless of whether you were born a biological male). Sometimes prisoners will tell you that a tattoo “means nothing.” But there is always some meta-communication potential simply because tattoos are not allowed in Czech prisons. The very act of getting an illegal tattoo behind bars, an act that is punishable by the authorities, sends a message. An illegal tattoo can not only complicate a convict’s time in jail, it can also jeopardise their chance of getting an early release. So behind bars, every tattoo in prison is important, even one that is only ornamental. At the same time, you have to perceive the person’s whole body: how they move or carry themselves, as well as where they fit in. You can have a very rigid code of tattoos and symbols, for example, when it comes to Russian-speaking inmates. There, you can’t just get any tattoo you like, especially if you haven’t merited it. The tattoo you can get within such a gang depends on your past and on your criminal career. There is a deep-rooted and traditional symbolism and a “correct” coding grid among Russian prisoners which is fascinating.

It reminds me, in a way, of outlaw motorcycle gangs where you have patches on your leather jacket that you have to “earn” and each one has a meaning.

In Russian gangs you definitely have to earn a tattoo and even more importantly you have to ask: there is a very rigid hierarchy. In every prison among Russian gangs there is a high-ranking member who has to approve, or even ask further up the chain in the outside world, for it to be approved.

In your research, tattoos that convicts had before they went to jail weren’t important, correct? Only the ones they got while they were there?

Yes. Often you would have inmates who had none and I learned that they would get their first tattoo within months of beginning their first sentence and imprisonment, obviously connected with the change in their identity behind bars. They would see others who had them and then choose to get one themselves. If someone cared about aesthetics in tattoos before they were jailed, they might make the effort behind bars also, to get original colours, or the best technical tattooing they could, and would wait for a capable tattooist. But if you were someone who didn’t care about quality even outside, who had amateur or homemade tattoos already on parts of their body, I think you took a similar approach in jail. The bottom line is that in the outside world, tattoos are more of an aesthetic matter. Behind bars, they are more about context and the message they send. Collective identity is very important and a tattoo shows which group you identify with.

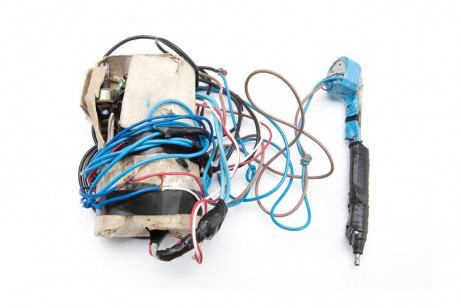

If you have ever seen some of the tattooing tools used behind bars, you’ll understand. Imagine a homemade tattooing device made from parts of a spoon, or a pen or a toothbrush, connected to a power source. And instead of needles, you havesteel brush wires. And yet, sometimes this results in amazing tattoos in the positive sense of the word. There are multiple reasons for getting a tattoo and it is significant that most inmates get their first tattoo within a month or so in jail. Their first, but definitely not their last.

Some of us are wary of going to even a regular tattoo parlour and would find the conditions in prison terrifying, I think.

Zero hygiene, there is really zero. Although even there, there are exceptions: it depends on the tattooist. Some don’t care and will use one needle for multiple prisoners, which is of course why it is illegal, because of Hepatitis B and C and other illnesses. But there are some who do their utmost to match the regular process outside: who clean the skin, who use aftershave as a disinfectant, who burn the tip of the needle first, and apply a cream to the skin afterwards, and somehow in that weird world of prison try their best to replicate conditions in the outside world. Some prisoners of course, were professional tattooists before.

Once you get a tattoo behind bars, is this something that should be visible, that you want to “announce” to others? Or is it enough, among the prison population, for others to know or simply have heard that you have it?

It depends. My first impression was that they were meant to be visible, such as the use of a teardrop by one’s eye, because of the connotations. [Editor’s note: a tear can designate a life taken – a murder]. But if we are talking about banned hate symbols like the Nazi swastika, those might not be as visible. I saw one on a person’s chest, above their heart. There are also inner lip tattoos, also not meant to be seen right away. Right-wing extremists will try and hide their tattoos and will tell you that their tattoos are only for them.

In prison it isn’t that smart to be public about a new tattoo which is barely dry, unless you really want to provoke the guards. But in cases where they are more visible, it usually relates to status. That can mean either higher status but in some cases also the opposite: you can be a victim, tattooed against your will, punished by fellow inmates for something that you did. These tattoos are often on the face, and can be everything from lines to depictions of male or female genitalia.

Readers can see many of the different types of tattoos in your new book. Right-wing extremists have all kinds of coded language, cryptic numbers and acronyms, it seems.

Yes, they use numbers but also colours and wordsand tattoos of their personal deeds connected to fascism. They are more and more sophisticated. So while many have the common ACAB, which stands for “All cops are bastards”, the right-winghas coded the message, for example, as 1312, where the number signifies the place of the letter in the alphabet. In the past, a prisoner might have had atattoo of a Klansman with his hand raised or the letters KKK but that has often now been replaced by the number 311 (meaning 3x the 11th letter in the alphabet). So they go deeper and deeper and the symbols go beyond runes or the swastika. Prisoners around the world, not here, sometimes pre- tend ACAB means “all cats are beautiful” or “all colours...”

You conducted hundreds of hours of interviews: what was it like to interview inmates, some of whom were in jail for life?

Most were quite willing and were fairly open. It took a while for them to trust me a little more and to show me tattoos of hate symbols or of their crimes and talk openly about what was going on behind bars. At the same time, they also often lied. The discrepancies in information over time were obvious, I’d ask some questions again and the answers would be different, and their stories varied from fellow inmates or prison guards. I think for them this was an opportunity to boost their egos and I think it is not unusual that people try and present themselves better than they really are. We all do that, in a way, even outside. In all, I did 205 interviews, including with guards and prison psychologists and others, 128 were with prisoners. That was the other side of the coin.

What kind of crimes had prisoners committed?

It differed quite a lot. I met some who were in and out of jail for lesser crimes and people who had been sentenced to 20 years with 17 years left on their sentence. I met people who had attacked others, or had stolen things, and I met hitmen who had been paid to murder someone. There were people from the Russian-speaking community, in jail for drug-related crimes, and I even met rapists who had hurt women or children. It was a question I had to deal with and I had to think about it a lot. A friend of mine, a prison guard who helped me, said I would have to be able to cope with the things I would learn – or quit.

But sometimes there were things that were hard to accept: a hitman who swore he would kill the people who sent him to jail once he got out. He was one of the very first interviews I did and it was like jumping into very cold water. But I had to push ahead. I would develop rituals whenever leaving jail: I would put on headphones and would listen to music as I headed home. But sometimes I spent a week or two at prison dormitories and just look at the prison in the distance. Sometimes I could think of little else. As a mother, it wasn’t easy for me to hear many of these things. But as a researcher I had to set my own feelings aside. It didn’t always work. I had a rule not to talk about my research with my family, but there were moments when I had to with my partner, so I broke it. There were moments when I felt I had failed as a researcher but not as a human.

Thanks to who I am, I meet people I would probably never otherwise meet. And they share with me what they might not have shared under different circumstances. This is what I enjoy: the dynamics of building an albeit short-term relation- ship, collecting data, analysing my findings, trying to understand. And that’s exactly what Charles University allowed me to do.

This work was the basis for your doctoral thesis at Charles University: how did you enjoy CU and how much did the school contribute to your becoming a professional researcher? I ask because you famously had a strong reaction to how cultural anthropology was taught elsewhere.

In fact, I originally began my doctoral studies at another university. After one of the prominent representatives of the Department of Anthropology there told me that research could be done just as well from the desk, I realised that I did not want to be a part of such an institution. I needed to be part of an institution where research is understood, where it was not about the quantity of publications but their quality. That’s why I applied to CU and I am very thankful that I was allowed to study there. It may come across as very critical, but to put it bluntly, an ethnologist who does research from their desk is a disgrace to the academic scene. At least for me.

Ethnology is about cognition, about entering the unexplored or even an explored field. It is about observation, about understanding and using one’s own optics to depict what is happening. Ethnology is about opening one’s heart, listening and trying to understand. You can‘t do ethnological research in a week or a month or even in half a year, and if you do, it probably won‘t be worth anything. I need people for my research and it’s fascinating for me to gradually uncover their world, which is quite often so different from mine.

| Alena Lochmannová, Ph. D. |

| Alena Lochmannová is a Czech ethnologist and economist whose primary research interests are representations of bodily modifications of (not only) convicts serving a prison sentence, including techniques for their execution and symbolic meaning, convicts‘ second lives and the question of identity in a total institution. Her research also focuses on the issues of radicalization and extremism, suicides and farewell letters. Lochmannová is the Vice-dean for Internal and External Relations at Faculty of Health Care Studies at the University of West Bohemia in Pilsen. |