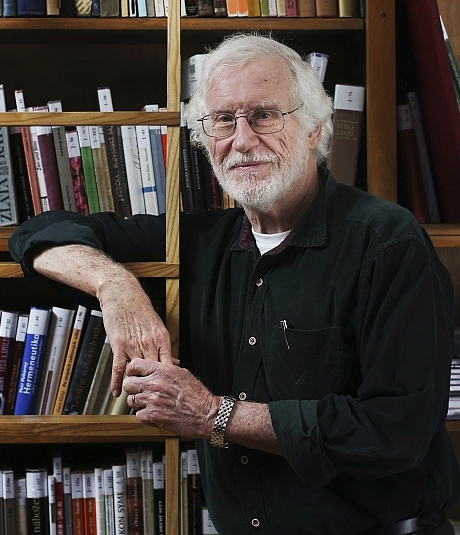

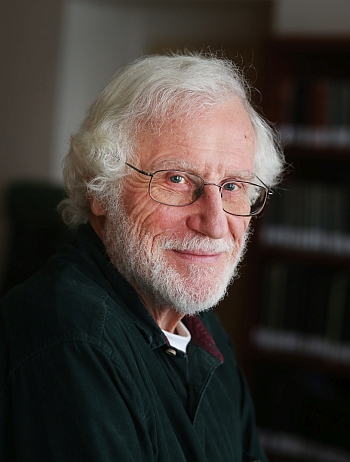

John M. Coggeshall is a professor of anthropology at Clemson University in South Carolina. As a cultural anthropologist, Coggeshall has spent his career researching American regional ethnic and social groups. He is the author of a seminal paper in the ‘80s examining gender roles in prison, and – most recently – an oral history called Liberia, South Carolina: An African American Appalachian Community. Coggeshall was a visiting professor at Charles University in the fall semester of 2019.

John M. Coggeshall taught two courses at the Department of Ethnology at the Faculty of Social Sciences in the fall semester - a welcome addition to the team at CU with extensive experience in fieldwork in the US. But Coggeshall was no stranger to the Czech capital: he first visited Prague in the mid-1990s. In the interest of getting to know Czech colleagues in 1995, he walked into the Department of Ethnology off the street and by chance met Dr. Leoš Šatava, a specialist in European ethnic groups; the two became friends and have been in touch ever since. More than 20 years later, Coggeshall saw coming back to teach as an opportunity and challenge: first, arrangements had to be made for someone to look after his and his wife’s house in the US. Then, he focussed on the needs of students he would soon be teaching.

I talked to professors here as well as a number of Czech students at Clemson University and they suggested that students here might be a little hesitant about speaking English. Both courses I was going to teach were discussion-based and I wanted the students to be comfortable. I made sure I wouldn’t be correcting them all the time in writing and speaking. By-and-large, I think everything went very well. In my anthropological theories class, for example, students were very engaged and their speaking ability was actually really good. I was very happy with how they responded.

Coggeshall has been teaching for more than 30 years; he himself studied to be an anthropologist in the 1970s and ‘80s, when new directions and focus in the field proved inspirational and even pivotal. A course taught by Dr. Charlotte Frisbie, he recalls, stood above the rest: the kind of course all university students hope for and, when they luck out, never forget.

It was called Women in Cross-Cultural Perspective. I think this was perhaps the single most important class I took, at either the graduate or undergraduate level. It opened me up to a lot of new ideas, including feminism. Other classes, such as introductory courses into anthropology were important when I was beginning my studies, but this one was revolutionary. This was it for me.

Traditionally, cultural anthropologists immerse or embed themselves in foreign cultures, using methods relying heavily on participant observation. In the 1970s and ‘80s more and more field researchers opted to study smaller groups “at home”. Coggeshall was fascinated by local communities in different states in his homeland United States that in the past had been largely overlooked or ignored.

I have always studied ethnic and regional groups and what I always find is that there are very interesting approaches to life in different American communities. How we can understand different approaches to life, and present them in a way that does them justice and also enhances connections between people, is what excites me as an anthropologist. What is hugely important is finding the differences that create identities among different groups of people yet at the same time link us together as human beings. The primary goal for cultural anthropologists is to study ordinary people in ordinary times and places; but I found over 35 years as a field researcher that the stories that people have to tell are extraordinary.

One of the groups Coggeshall studied in the 1980s were inmates in medium-security prisons. Initially, he hadn’t set out to study them at all. It was something of a happy accident.

It was a coincidence. I was hitting the jobs market and I needed teaching experience. I noticed an ad asking for instructors who would be interested in teaching university-level courses at men’s prisons in Illinois where I was doing my dissertation. I thought I could try it. The idea was that prisons would offer remedial high school courses, what they call a GED (General Education Development), and then university courses so that once inmates would be released they could find better jobs and hopefully start a better life. It was a popular program in the 1970s but later phased out by the government as being “too soft on crime”. But at the time I think it was fairly successful.

While teaching, Coggeshall says he eventually began taking notes and interviewing guards as well as the students themselves before or after class just to get a better sense of “what life in prison was like”. The atmosphere in the classroom was positive, the building where he taught, modern and new, the students generally well-behaved. There was a guard in the facility but not in the classroom itself and essentially Coggeshall was alone with 15 inmates at a time. He smiles when he tells the story of one time the education building lost power and the lights went out. At the head of the class, he exclaimed “Alright, nobody move!”. Remembering the moment, he laughs: “They all thought that was the funniest thing they had ever heard”.

Such moments are humorous but in the context of prison using one’s authority to set clear boundaries and rules was important. Enforcing them was something Coggeshall learned to do early on.

That is kind of the first thing you learn in prison: to set boundaries and try not to back down. I did that fairly successfully. If I hadn’t, the inmates themselves later admitted, they would have continued pressing and would have tried to manipulate me. It’s not an uncommon behaviour but the consequences are obviously greater in prison than elsewhere.

Because his students were well-behaved, Coggeshall says he initially thought most were in prison for white-collar crime or crimes like auto theft; but soon he learned that there were inmates in his classes also in prison for murder. One of the most diligent students was an African American who, it turned out, was serving multiple back-to-back sentences for racially-motivated murder after coming back from the Vietnam War. He had served but had gotten involved in drugs and was thrown out of the army. Back in America, he had gotten involved in a gang and, Coggeshall learned from microfilm archives, had attacked a white suburb in Chicago, resulting in multiple killings. Despite having turned a new page in prison, this was an inmate who would never be getting out.

The anthropologist spent three semesters teaching inmates before he felt he had had enough of life behind bars. But the information he had gathered, combined with some interviews done by an inmate friend (a former student), provided the basis for “‘Ladies’ behind bars: a liminal gender as cultural mirror” published in Anthropology Today (since reprinted in The Best of Anthropology Today, ed. by J. Benthall (London: Routledge, 2002).

The article explored gender in prison, essentially how some inmates were emasculated or forced into female gender roles that were to no small degree a distortion and caricature of behaviour and male/female relationships in the outside world. The article pointed to aspects of power, intimidation, sexual violence and abuse but also, importantly, inmates’ responses, from acquiescence or acceptance to resistance as part of survival strategies, some successful, some less so, all within the gender framework. In short, gender in jail had little to do with one’s biological sex but was determined by one’s standing (or lack of it) within the overall power structure among inmates. The article, which is a powerful read even 30 years on, began to take shape mainly after Coggeshall was approached by a colleague.

I was at a conference and Pam Frese was putting together a session on gender. She asked me about the German Americans I was doing my dissertation on at the time but I said the material I had gathered in prison was suitable. It’s complex and when it comes to the fluidity of gender, there might be multiple factors involved in prison: but there is a dominant/submissive relationship.

Men’s prisons see a lot of sexual violence and rape, at least they did in the ‘80s when I did my research. I am positive [being subjugated to a female gender role] is not inevitable for a prisoner: you can put muscle on, or gain power through education or legal means, or if there is something you can trade there are ways to avoid it. It doesn’t happen to everyone, but those who are considered weak, who fail to stand up for themselves, who have elements of femininity, are picked on and effectively are “selected”.

The article gained a certain “notoriety” and Coggeshall says after publication he received an offer to expand his research in a book, but in the end he declined. He says he didn’t want to become known as the anthropologist who studied state prisons; he had many other ideas he wanted to explore. At the same time, he readily admits the article remains one of his best-known and there’s no question it was an inspiration for many, including Czech anthropologist and CU graduate Alena Lochmannová who met Coggeshall during his stay. She herself spent hundreds of hours interviewing inmates in prisons in the Czech Republic for her own dissertation on prison tattooing (you can look forward to an upcoming interview with Lochmannová in iForum).

The prison paper was getting a lot of attention but my dissertation was about German Americans in southern Illinois. What was really interesting for me is how one ethnic group differentiated from another, as well as the stereotypes they often faced and traditions that really distinguished us from them. I have also always been interested in regional groups and in South Carolina. Early on, I figured out that if I wanted to be a top anthropologist I needed to specialize, but I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to remain a generalist. For me, that meant studying different groups besides inmates. Being a generalist and exploring different subjects made me happy.

One of Coggeshall’s most recent publications is Liberia, South Carolina: An African American Appalachian Community (University of North Carolina Press, 2018). It is a fascinating oral history that branched out of another project, initially.

I was given a project another researcher turned down and the aim was to document the lives of – the assumption was white people of Irish-Scottish descent – who lived in mountain areas and who had been displaced due to a hydroelectric dam. The valley they had lived in before was now under water. So I began interviews and what was fascinating was the way they talked about land.

I grew up in the Midwestern United States and land is considered property with a value attached to it which you buy or sell and it’s not an integral part of who you are. But these people spoke about land as an integral part of their families. Their land had been in their families for five or six generations, they told stories about it, land became a part of their identity and it was a part of who they were. And to lose that land had meant they had lost a part of themselves. And I thought that would make an interesting subject for a book.

Doing research, the ethnologist came across the name of Liberia Road on a map – an unusual place name in such a vicinity.

The southern Appalachians pride themselves on a Scots-Irish, maybe some German, but basically Euro-American settlements and here was this African place name in the middle of what is often seen as being a traditionally “white” space. So I drove up there and happened to meet a woman who turned out to be the matriarch of this Liberian community.

So I set my mountain book aside temporarily and began to study a community of African Americans who had descended from slaves who had been on the very same land before the American Civil War. When they were freed and given land in exchange for their labour, many of them stayed. A few descendants managed to hold onto the land ever since, despite there being plenty of forces over the decades prior to drive them out. The matriarch, Mable Clarke, was really involved in the project and the proceeds from the book are also going to the local church.

Studying even a tiny community like that at Liberia Road, counting just a few houses and people, proved immensely valuable says the anthropologist, providing a new thread which inevitably challenged or complemented more traditional and dominant narratives.

Hearing their side of the story was important and it was fascinating to plug that into the story of South Carolina and even American history in general. For me, their community is a microcosm of a century-and-a-half of the American story and it’s important to hear their side because that is heard far less often than white versions of history. For me it was a life-changing experience.

Meeting with John M. Coggeshall in the same office he walked in off the street in 1995 must have been curious for the anthropologist; certainly Charles University is proud to have had him as a guest lecturer from Clemson for at least a few months. If Coggeshall sounds almost wistful that his stay in the capital has drawn to an end it is because he could probably envision staying a little longer. Next time.

We really enjoyed it. My wife, Cathy, now retired after also teaching at Clemson, took four months of Czech while we were here and is a lot better at Czech than I am. We love travelling and different cultures and we really loved being in Prague. We both talked about it before I took this job as there were things we temporarily had to leave behind, but we decided that it would be an adventure and that it would be worth it. I loved our time here and getting to know my colleagues, my students, the culture and the city. I would come back in a second!

|

John M. Coggeshall is a professor of anthropology in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology, and Criminal Justice at Clemson University in South Carolina. He received his Ph. D. in anthropology from Southern Illinois University-Carbondale. His interests and activities centre on American regional and folk groups and sense of place in southern Appalachia. Notable publications include Liberia, South Carolina: an African American Appalachian Community (University of North Carolina Press, 2018), Carolina Piedmont Country (University Press of Mississippi, 1996), and “‘Ladies’ behind bars: a liminal gender as cultural mirror” reprinted in The Best of Anthropology Today, (Routledge, 2002).

|