Almost six months have passed since tragedy struck the Faculty of Arts at Charles University: a mass shooting that claimed 14 lives. CU has since responded with key measures. The head of the Central Crisis Staff of Charles University Otomar Sláma and security expert Zdeněk Kalvach discussed steps already implemented and crucial steps still to be taken, with Forum magazine.

What has changed at Charles University since the terrible event of 21 December last year?

Otamar Sláma: First, I think I should say that we have been assured by security forces that there is no acute further threat of a similar such event repeating, nor have any signals been registered to that effect. The university has further intensified or closely focused on its cooperation with the police, we have a range of support in the form of psychosocial assistance for students and staff, sound detectors are being tested, training sessions are underway, and the internal crisis information and call system are being tested.

Charles University has also approved an updated security plan for 2024 and 2025, which we have consulted with the Ministry of the Interior, the police, the integrated rescue system, psychologists, as well as domestic and foreign experts. The aim of this plan is to increase security across the board at all faculties and buildings of the university. CU has 72 sub-points in terms of crisis response that are being implemented in every faculty and every unit of the university.

A topic discussed in the public arena was whether the number of cameras at the school would be boosted or whether walk through metal detectors would be introduced. What is your stance?

O. S.: We are often asked by students and faculty representatives whether it would be better to have more cameras and walk through metal detectors inside building entrances. That this is not the direction we want to take. First, it’s inefficient to install detectors at 190 buildings or to replace all windows at facilities with bulletproof glass. That is simply not feasible. More importantly, it would not solve the problem.

Imagine a situation where you have installed walk through detectors: a potential shooter knows they wouldn’t pass undetected which means that if it comes to it, they will launch any attack right at the entrance. Having a metal detector necessitates having an armed security officer nearby, always on the lookout for a potential attack. And it's not enough just to have a frame, you also need an X-ray machine to check bags and nearby room for example for shoes to be checked, like at the airport. Any such changes would require a lot of staff, and lead to long delays and inconvenience. That's not how we want to spend our time at university.

When we explained the details to students during open discussions, they appreciated our honesty and straightforward approach.

Zdeněk Kalvach: We have experience with attempts to increase safety, when so-called soft targets are transformed and strict or hard measures are applied. The worst thing that can happen is that a lot of resources and especially hopes are invested in something that ends up not being effective. Years ago, security checks and check-points were introduced at Prague Castle under the former president. They have since been dismantled but at the time? The result was that long queues of visitors formed [and a bottleneck was created]. These lines became one of the most vulnerable areas at the Castle.

When we talk about soft targets in general, which universities inherently are, when we talk to people from the Interior Ministry, from the police, experts from the FBI, from Israel, from Norway, they all agree on one thing: you can never completely prevent an attack against a soft target. Unless you make the facility a hard target, which means making the school an airport-type facility and going two hours early every day to go through the whole checkpoint. Charles University has decided it doesn't want to go that route.

| What are soft targets ? |

| Soft targets are facilities that do not have strong security, are usually freely accessible to the public and not subject to the type of security checks we know from airports or embassies. Because of the high concentration of people - or symbolism of places - soft targets may be attractive to a certain type of attacker. Shopping malls, schools, metro stations with a large flux of people are all soft targets. |

You met with FBI agents who have extensive experience with shootings in American schools...

Z. K.: The main message of our meeting was to discuss working with threats and anticipating inappropriate behaviour, prevention, creating a certain "safety culture" that has been building for a long time. Some measures and procedures need to be gradually adopted so that they become routine, while sensitising students and staff to react to safety measures. What is happening now is that every arrival of uniformed police or closure of a part of a building due to the discovery of a suspicious object causes heightened concern and significantly complicates routine procedures.

I had the opportunity to examine a study that addressed how American schools approach security concepts. Among other things, it looked at what measures were taken by schools immediately affected by the shooter's attack and what measures were taken by schools in the surrounding area, several miles away. It turned out that the schools immediately or most affected did not follow the path of hardening security. They took other measures - for example, introducing more green spaces, more rest areas, more community work, more support actions and psychological interventions, more safety drills. It was more essential for them to improve their “community culture”. By contrast, schools not immediately affected by the attack tightened or enhanced their security. Kids had to wear transparent backpacks making it impossible to conceal a weapon, metal detectors were added, kids had bulletproof blankets they could reach for in case of an assault... Interestingly, the schools' measures were related to how much fear was in the air, how much there was a sense of imminent attack.

And did people in schools with stricter measures feel safer? Or on the contrary, did they become more stressed?

O. S.: Security measures complicate normal operations and lead to various forms of stress. All we have to do is talk about metal detectors, X-rays or some random checks as we know it from airports. It means that someone stops you and asks you to do something, invades your privacy, and this, of course, opens up the possibility of a number of other complications: who do you select for the check, how thoroughly is the check carried out and by whom. All this can create very uncomfortable situations for everyone involved.

If these hard or stricter measures are not planned, what are steps are you pursuing? CU, for example, wants to ban weapons from being brought into school buildings.

O. S.: We have currently had the opportunity to see a draft amendment to the Higher Education Act that would make this explicitly illegal, because we currently have very limited options. We perceive a great risk of situations where people want to take protection into their own hands and go to university with a weapon, even one that is legally held.

Some people who hold a gun licence have the naive idea that they would be able to make a difference in a situation like the one at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University on their own (they underestimate how things unfold in real life – editor’s note). Professionals who know how to handle a gun themselves and are trained in tactical shooting know that you are much more likely to shoot or injure an innocent person in tense situations. The idea that someone can do well just because they have a gun in their backpack is very misguided. Armed non-professionals also often don’t know how to identify themselves to security forces moving in, who only see a person holding a gun. That situation can lead to a tragic [misreading of the situation] and outcome.

Charles University now has camera systems that can respond or distinguish between different types of sound.

O. S.: We have these cameras installed in a test mode in the Carolinum and in a building in Celetná Street, over 50 of them. The cameras have a special microphone with appropriate software that is able to evaluate sounds that should not be happening in the room - for example, glass breaking or distinguishing a normal exclamation from a scream of someone who is evidently in distress. After all, a person whose life is on the line screams differently than someone who just shouts loudly at another person.

There are hundreds of cameras placed throughout the university buildings and it is not humanly possible to monitor them all at once, and this system can assess a dangerous situation and alert you that something unusual is happening in a particular location. The operator at the CCTV system will then check to see if someone just banged the door by mistake and it was a false alarm or if there is cause for concern. The detectors significantly reduce our response time because we can immediately see exactly where the problem is and can respond accordingly. But these systems are still being tested and need to be fine-tuned.

Z. K.: Moreover, the work is not done by these cameras, but by their operators. We have to pay attention to increasing the ability to react correctly. Otherwise, all we have on the wall is more sheet metal and wires for a lot of money.

Otomar Sláma and Zdeněk Kalvach with the Dean of the Faculty of Arts of Charles University Eva Lehečková and CU Rector Milena Králíčková.

One new feature is the introduction of a crisis information and convening system.

O. S.: Until recently, we tested the Crisis Intervention and Call System (KISS) in the dormitories and canteens and at the Rector's Office, but we are currently extending it to all faculties. This system allows us to communicate up to eight different ways at once any message to all students and our staff. It can also be sent to a specific group of people - staff only in a specific faculty or only to members of crisis teams, and possibly run automated pre-prepared emergency scenarios. For example, messages can look like this: There is an armed person in the building; if it is safer than fleeing immediately, lock yourself in your rooms. If you are outside the building, stay away. Then let your supervisor know you are okay. Or: There is a fire in the building, quickly take the nearest escape route out of the building. Leave all belongings inside. If you are outside the building, do not come closer. Then let your supervisor know you're okay. You will receive a text message like this in the event of an emergency.

There have already been training sessions at some faculties and individual scenarios are being prepared for each to run. We are training authorised persons like deans and other administrative staff who can activate the emergency scenario. This is because, in addition to the technical procedural setup, the mental preparation of those who have to send such an instruction in a stressful and often ambiguous situation is very important.

The entrances to some of the newer CU buildings are secured with key cards, is this the way to greater security?

O. S.: We often face the fact that our staff and students would like to be able to lock themselves in. But just look at the traffic in the faculties and how many people enter rooms as it is. Students who are late to class will then interrupt you because they knock. You carry key cards, but what if you forget? Someone will lend it to you or let you in. Turnstiles won't solve or deter an attacker who is thoroughly preparing for an attack. And if the attacker happens to be a student, they’ll have an access card as well.

Z. K.: Turnstiles sometimes have their importance, but not as an aspect of security, it's more of an organisational measure - to monitor attendance or how certain rooms are used efficiently. But let's not forget that at a public university anyone has the right to come to a public lecture.

O. S.: In addition, there are a number of staff in the buildings. If you walk by with a ladder and explain at the main desk that you're going somewhere to fix something, you'll be let through. And in principle that's fine, that's how things should be. We've got cleaners, maintenance staff, IT people, other workers, there's a huge turnover of people that you'd otherwise have to filter through all the time.

Charles University has almost 200 buildings, you probably can't apply the same measures to all of them, either, can you?

O. S.: We have buildings that are brand new, and buildings that are hundreds of years old and have completely different parameters: different types of windows and doors, different types of rooms, somewhere there are thick stone walls, somewhere there are plasterboard walls. From 2021 to 2023, we have gone through all the buildings of Charles University, there are just under 200 as you said, and we have conducted soft target protection analysis on all of them. We also measured potential risks in terms of where they are located: whether there is a risk of flooding or arson attacks, or what the crime rate is in the area. And now detailed SWOT analyses of each building are being carried out. Room by room.

We have a list of absolutely every room, from the largest hall to the last warehouse, and for each room, information is entered on whether it is suitable for lockdown, what type of windows and doors there are, which side the doors open on, and how good the quality is. Whether there is ventilation in the room and what alternative means of egress from the room is available. And based on these detailed analyses, individual measures will be considered for all buildings.

In the Faculty of Humanities, for example, the windows in the large glass lecture hall have been fitted with aesthetic cladding and curtains. These will prevent a potential attacker from seeing inside and, in addition, will at least partially limit shattered glass in the event of a break. It's an investment, of course, but not dramatic in relation to how much good it does. These are such small and relatively inexpensive measures, just like door stops. There are auditoriums where all the tables and chairs are bolted to the floor, so you have no way to barricade the entrance.

Z. K.: We have a team of people who are trained to collect data on our buildings. They fill out the data, including how big the rooms are, how many people they can hold. There are about 15 parameters that we're able to assess each room against. There are types of rooms suitable for barricading that we can recommend to staff and students for lockdown. Then there is a group of rooms that come out as unsuitable and modifications would mean extraordinary interference with the construction of walls and other things, in which case it is better to recommend moving to safer locations instead of complicated renovation. And then there are rooms where relative safety can be ensured through minor modifications.

For the future, the analysis highlights rooms on the first floor or in the whole building that can be converted into a larger room that can accommodate more people, and it makes sense to add, for example, an expanded pharmaceutical kit, an emergency kit that contains water, grape sugar, and hygiene items, in addition to the normal first aid kit, and other things to be able to spend about two hours there in relative safety.

Zdeněk Kalvach (left) and Dean of the Faculty of Arts of Charles University Eva Lehečková.

O. S.: The public has now turned its attention to the danger represented by an active shooter, because that is what we experienced, but there are many more potential threats and many measures go slightly against each other. An attack doesn't just have to be the use of a firearm, we can talk about arson attacks, chemical attacks, or accidents like a gas leak, blackout, or fire.

And if, on the one hand, we are trying to secure rooms so that an attacker cannot get into them, then again you have a number of situations where you need to get into the rooms. For example, if someone has a medical problem in there, like someone collapsed. So either you need to get out/inside quickly, or you need to barricade yourself effectively. But the more barricades you build, the harder it is logically to get out, or for paramedics who need to get to you.

Security is, in short, a complex issue that needs to be looked at from many angles. Every environment brings some disadvantages, but most of them can be addressed in an improvised way. And if it's a room unsuitable for hiding safely, I need to know about it in advance and work with the fact that I shouldn't hide there and need to go elsewhere. And there's an awful lot of educational work involved in that, and we want to do it right, and not hastily replace doorknobs with ball doorknobs everywhere now, and then find that in the event of a fire, the fire department wouldn't get in, in time. These measures have to be done very sensitively and deliberately.

Z. K.: And finally, the focus will be on the readiness of individuals to use what they can to save their lives. To do this, they do not need so much technical adaptations, but above all mental and physical resilience and basic knowledge, which we are now reinforcing with the various tools mentioned.

Will the university therefore seek to prepare staff and students for crisis situations through, for example, training?

O. S.: When we announced the intention of safety training, some groups of people felt that it was still early days – too soon after what happened – and that’s understandable. From others we heard the impulse “it about time something was done”. It's a lot about choosing the right moment and effective communication.

Charles University has decided not to go down the path of choosing hard measures, so we need to focus on prevention with other tools. For example, by training people to be more attentive: if someone has left an unattended bag behind, or to notice if someone is behaving strangely, that this person has no business being here, that a colleague or classmate is becoming radicalised, etc. The English language has an apt slogan for this, 'If you see something, say something', which is the best thing you can do when it comes to prevention.

Z. K.: We are going down the path of resilience - to be able to absorb crisis situations and to try and curb the impact. So that the people who are immediately present know as much as possible about the situation and how to responnd properly. That they can run away or make a barricade, not to leave safe rooms at the wrong moment... and to think ahead. So that it's not just intuitive that people are calling each other, but that we strengthen the warning system, clarify the mode of warning messages and what a warning message should look like, so that it doesn't tell people to hide when it's better to run away, or to run away when it's dangerous.

We set up several training sessions that we address with each faculty individually. First, we train staff so they know what to do in different situations. There are also specialised blocks of training people staffing entrance desks, mailrooms, study departments, libraries or student services, or places where people congregate often. And there is also specialised training for faculty leaders so they know what can go wrong in crisis management - for example, when they receive information about suspicious abandoned luggage, suspicions about a student, or other miscellaneous concerns.

Discussion with the students themselves is also extremely important to us. Some meetings have already taken place, for example, in the Faculty of Arts and the Faculty of Humanities. And we are happy that students ask questions and have a number of suggestions. We provide them with as much information as is useful for them, so that they know the procedures, but most importantly our thinking about the principles of protection.

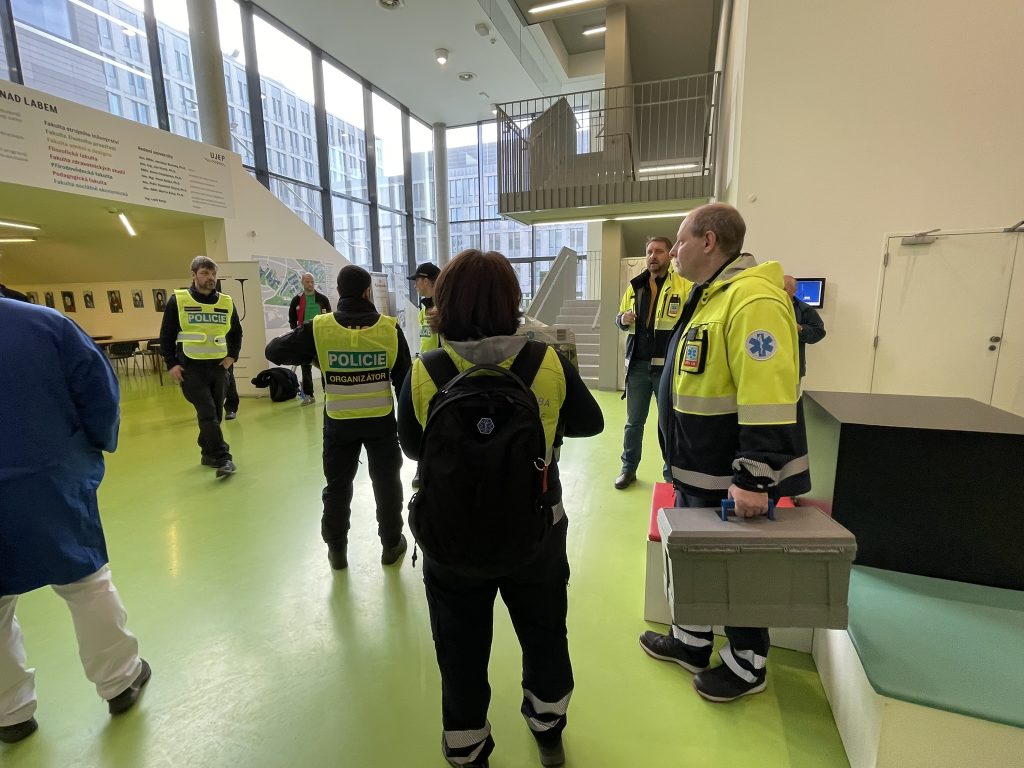

At Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem they recently had a training simulation or exercise to test and help prepare the response in case of a shooter attack. Is something similar planned at CU when the time is appropriate?

O. S.: We plan drills with individual faculties according to how willing, able and prepared they are to do so. We are not only talking about evacuation drills, but also AMOK drills, i.e. simulating an attack. And that needs to be very well timed so that we don't scare our students, that's obviously not desirable. Such exercises have to be done over time and with consideration of the psychological impact. A number of drills had been planned already but postponed for these reasons.

It is also problematic for many people at the moment to talk about being actively involved in the process in the event of an emergency - that they should evacuate quickly or lock themselves in and hide somewhere. Simply that they should play an active role in their own safety, in a crisis situation, if they can.

Jan Evangelista Purkyně University in Ústí nad Labem. Photos: Czech Police a UJEP.

It may be shocking at first to go through such an exercise, but the hands-on experience is invaluable, no?

Z. K.: Yes. But it has to be done at the moment when people are able to absorb it properly. If we have too much fear and disturbing elements in an exercise with figures simulating real danger, people will not walk away strengthened, but on the contrary they may be even more traumatised. We need to wait. Sometimes we get people's uncomfortable emotions even in the training itself, often with people who have been affected by the tragedy at the Faculty of Arts.

We also have a proper fire evacuation drill on the checklist, which could be graded in terms of the intensity of the experience itself. And at the same time, we'd like to have a number of assistants there to monitor the whole process and a number of details - how loud the alarms are, if somewhere, for example, they're not audible, or if somewhere, on the other hand, they're so loud that you start to panic just from the sound of them. How we get overwhelmed in corridors that may formally meet the evacuation route regulations, but in reality we may discover new facts. We find that people don't actually know where to go. It's important that we get realistic feedback on many aspects that traditional fire drills don't address.

O. S.: The drills are not just about getting out quickly, but the follow-up is essential - we want to find out how the message of a crisis situation is conveyed: is a student running to the entrance desk and reporting an alarm? What does the doorman do? Who does he call? Does he first call the fire department, or the dean? Or does he push a button? And what happens when he pushes the button? How long before the fire department arrives? How long before the dean responds and calls who? What scenario will he run and will he run the crisis information and call system and send out a message or will he call someone else first? How long did the whole process take?

Related to this is the crisis preparedness plan.

O. S.: This is a non-public document that contains so-called action cards for each possible crisis situation. The cards describe the correct procedures, whether I call the police first or inform the university administration, when I convene the crisis team or when we send a straight message through KISS... So that it is clear in what order and what instructions are to be given. There are dozens of such scenarios: there are arson attacks, the active shooter, barricade situations, various accidents and natural disasters like floods or blackouts, gas leaks, explosions and many others. Mass disasters, such as a bus accident with students, are also considered.

In the event of any such situation, an authorised person will pull up a specific scenario and everyone will know what to do in that situation. This plan was recently approved by the extended Rector’s Board. In collaboration with faculty and other constituents, the same plans are being adapted at the faculty level to reflect local needs. Medical schools, for example, are typical in that students spend a lot of time at the faculty and also at the hospital next door. And the hospital is no longer our building and has slightly different procedural steps so that, for example, that fact is taken into account.

It should be noted here that each faculty has its own crisis team that takes charge in times of crisis.

O. S.: Each crisis team is typically made up of selected members of the management of a given faculty or unit. There is usually a dean, a provost, administrative person, some appropriate vice deans or associate deans, and a security officer or coordinator. It is also made up of executive members involved in communication with students, staff, victims, and the media. These may be assembled on an ad hoc basis, depending on the availability of the moment. The staff thus has a structure, but above all it must be functional and effective. Unlike state and local government crisis staffs, soft targets have much more freedom, and we take advantage of that. It must meet within two hours of being called.

At the same time, there is a central security team in the Rector's Office - the Security Department - to methodically lead and step into a crisis situation, as in the case of the events at the Faculty of Arts. At the moment of such a major incident, the Central Crisis Staff was immediately activated, which complemented the crisis staff of the Faculty of Arts and was fully active until 21 April of this year, thus functioning continuously for four months after the tragedy last December.

Z. K.: The faculties really have professionals at the level who can handle potential crises now, because it is mainly about effective and premeditated communication with their own people from the faculties. They know the agenda, how to communicate with the staff and the media, how to handle things professionally at the management level. A crisis preparedness plan will help them organise everything and give them the competency to know what role to play in a crisis and to know what steps to expect in the first hour, in the next hours, the morning after an incident...

What is in store for students and staff in the security field in the near future? Will there be a possibility to receive training?

O. S.: Yes. But we have over 10,000 employees and over 50,000 students, so the idea that we would now train such a huge number of people in a few months is unrealistic. We want to train as many people as possible in person, so that they have the opportunity to debate and discuss. For now, we don't want to go the way of some other schools that have made an instructional video and shared it. While that is effective for distribution, we have not opted for that simplification.

We're going from the faculty leadership through the staff, who are actually the ones who are expected to handle the crisis situation and give instructions to others in the event of a crisis. They need to know what to say and do when they are approached. But we also want to go to the students, which is happening with some faculty who are very proactive in this regard, typically students in the Faculty of Arts, where they are expressly eager for information. We have already done several seminars there.

Z. K.: We are currently finalising the preparation of two pilot types of training for students, which were of the greatest interest during discussions with students: specialised first aid in incidents and physical training in model crisis situations.

O. S.: It’s important to keep our feet on the ground: there will be enough time for the training and it will not be mandatory for everyone. Normal life has to go on, we go to school, have state exams, deal with budgets, submit grants, and occasionally go to safety training just like any other training. It shouldn’t be taken as dogma that everyone now has to rush through all the safety courses at once.

| Otomar Sláma |

| Otamar Sláma is a member of the Rector's Board for Knowledge and Technology Transfer and Security. Since the tragedy at the Charles University Faculty of Arts he has been the head of the Central Crisis Staff of Charles University (since 21 April 2024 the staff is no longer active). |

| Zdeněk Kalvach |

| Zdeněk Kalvach is the co-author of the Ministry of the Interior's methodologies for the protection of soft targets. He was head of security of the Jewish Community in Prague and later deputy security director of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty. He also works as a psychotherapist. |