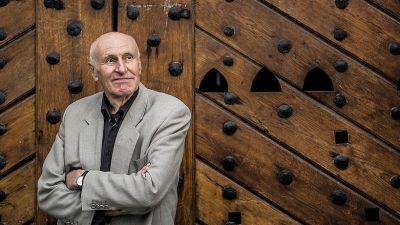

Peter Mackay is a man of many interests and talents: he currently works as Senior Lecturer in the School of English at the University of St Andrews and has been hailed by critics as the best poet of his generation writing in Scottish Gaelic. Not only that, but he also serves as the captain of the Scottish Writers’ Football Team.

Poet Peter Mackay was photographed in a 'contemplative mood' by the Vltava River by Forum's Michal Novotný, in the autumn of 2023.

Czech scholar Petra Johana Poncarová met up with the Scottish poet and academic in Prague recently on behalf of Forum magazine. As an accomplished translator from Gaelic and having translated Peter Mackay’s work as well, Petra was ideally placed to discuss his poetry, gaps in Scottish Studies, Mozart, and the strategic partnership between Charles University and the University of St Andrews. A great interviewer and interviewee. Forum extends thanks to both.

You are a respected academic and an acclaimed poet. The twinning of these roles is not an entirely unusual one, but how has it worked for you: what are the benefits and the drawbacks?

It is very hard to make a living as a poet; but it is also very hard to make time to write poetry when doing a full-time academic job. At its best, the reading and thinking for the academic work opens new windows, excavation points, cloud-rifts that poems can slip through – and which can then feed back into new understanding of the books I am discussing, the odd literary histories I’m exploring. At its worst, it is difficult to get the tone of whatever one is writing just right: even one overly academic syllable can sink a poem.

At the stunning University of St Andrews. Shutterstock

Thanks to the strategic partnership between Charles University and University of St Andrews, you recently gave a lecture at the Faculty of Arts in Prague and also a poetry reading at Kampus Hybernská. However, this was by no means your first visit to the Czech Republic. When and how did the first one happen – and how have your experiences of the country been so far?

I’ve been travelling to the Czech Republic since 1997, when I interrailed from Germany to Spain, on a very circuitous route. The summers of 1997 and 1998, in both of which I visited the Czech Republic, have a particularly golden hue in my memory, and I almost stayed in Prague for six months in 2001 (until life intervened). I have been back repeatedly since: to Olomouc for poetry workshops, for conferences and readings in Prague, and to Opava for the wedding of an old friend and flatmate of mine, who is from there. The country is always intellectually and artistically bracing; there is a gear-change about being in Prague especially, of feeling oneself dipping into a long current of artistic play and seriousness. Literature matters here, to an extent that is not all that common.

Have you come across anything from Czech culture – literature, cinema, visual arts – that has become of particular interest to you?

I am limited, unfortunately, to the literature that has been translated; but in this I have still found some books that have stayed with me for years. The Willa Muir archive is in St Andrews University and her translations, with her husband Edwin, of Kafka’s work I’ve loved since I was a teenager. The poems of Miroslav Holub (who I discovered through Seamus Heaney) and the remarkable novels of Bohumil Hrabal I came to later, and there are a couple of moments in I Served the King of England (Obsluhoval jsem anglického krále) that still tap away on the edge of my subconscious. I love the films of Miloš Forman too, but also those of Jan Švankmajer – one of the best literary events in Edinburgh, the now-defunct Neu Reekie, mixed poetry, music and animated films, and Švankmajer’s work was always a highlight, a mind-bending treat. The tongue being pulled out in Food (Jídlo) still gives me the shivers.

You gave us permission to reprint your poem inspired by W. A. Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto in this issue, which is a lovely touch as Prague is so closely connected with Mozart, and the poem also demonstrates the ability of Gaelic writing to encompass any topic that intrigues the writer. What inspired you to write that particular poem?

The story of the Clarinet Concerto was particularly resonant for me. Not just that it is likely to have been premiered in Prague, but that the manuscript score is lost, and even the instrument it was composed for, the basset clarinet, was rarely played, so the score had to be adapted. There was a metaphor here for loss, and cultural transmission, the way that music (and all culture) can survive in some form, even if not that originally expected: and there was a welcome parallel with the way in which the Scottish Gaelic language exists in the contemporary world, energised by many adult learners. But there were other kinds of loss involved too. I’d just been playing with the Scottish Writers’ Football Team in Vienna, where I’d visited the church in which Mozart’s Requiem was first performed. And we were absolutely destroyed by the Austrian football team by a score of 9–1. We were terrible: quite a different kind of loss?

|

Mozart: Concerto airson Clàirneid, A major, K. 622 |

Mozart: Clarinet Concerto, A major, K. 622 |

|

Thèid corra rud a chall gu sìorraidh bràth. Rudan eile, cha tèid. ’S e am pìos mu dheireadh a chrìochnaich Mozart Concerto ann an A major airson clàirneid bassinet – ionnsramaid a rinn a charaid aig’ Anton Stadler. Chaill esan an sgòr cha mhòr sa bhad, agus an ceann deichead chaidh a’ chlàirneid aig’ fhèin às an fhasain ’s à eòlas. Call air chall. Mozart ann an uaigh gun ainm ann am Bhienna. Am pìos ciùil aige na mhac-talla air ionnsramaid cheàrr ann an dùthaich chèin. (Ach be dammit, beò, air chrith.) |

Some things are lost for ever. Some not. The last piece Mozart wrote was a concerto in A major for basset clarinet, an instrument invented by his friend Anton Stadler. Who immediately lost the score and whose instrument went quickly out of fashion, and then out of lore. Loss on loss. Mozart in a common, nameless, grave in Vienna. His concerto reconfigured, echoing on the wrong instrument. (Yes, but still echoing, dammit, still alive, vibrating.) |

Published with permission from the author

Your Gaelic poems have already been translated into a number of languages. How do you feel about your work spreading in this way? Do you work closely with translators, or just give them a free hand and hope for the best?

I’m always delighted for my poems to be translated into other languages, especially if they can be done directly, without English ‘bridges’ – including the translations you did, Petra, into Czech. There is something high-wire and liberating about Gaelic being kept apart from English, and allowed to have its own conversations with other languages, without being overheard or surveilled by that neighbouring language. Many others do require a bridge. That does require a different process, but also has its own pleasures and opportunities – the bridges I give would tend to show just how wide-ranging some Gaelic words would be in comparison to the English; the bridges themselves undermine and pick away at the English. With the translators, I enjoy working as closely with them as they choose; however, I would always give them a free hand in the end, and trust them. I’ve been lucky to work with excellent translators who I respect for their skill and craft: it would be … foolish to be too controlling.

Your academic work has a broad reach, including Irish Studies, but you have been publishing a lot on Scottish literature in general and on Gaelic writing in particular. Scottish Studies and Gaelic Studies are both relatively young and growing disciplines, and surprisingly little work has been done even on some major writers and essential topics. What strikes you as the most important challenge for people working in these fields? What is most needed?

As you say, there is a huge amount of work that needs to be done on even major figures in Scottish and Scottish Gaelic Studies. The political and cultural relationship between Scotland and the rest of Britain is probably behind this to some extent: the comparison with Irish Studies, with the whole weight of a national imaginary and a sizeable North American diaspora behind it, is telling in this way. So, we need the expanding of the canon, critical editions of many authors (Naomi Mitchison is one of the most interesting 20th century novelists; the 18th century Gaelic poet Alasdair mac Mhaighstir Alasdair doesn’t have a collected work of poetry solely to his name; the hugely important book of the Dean of Lismore has never been fully translated and edited), and a huge amount more academic discussion. There hasn’t been a wide-ranging analysis of contemporary Scottish poetry for almost 20 years. Much good work has been done, and the situation is improving, but there is still a need for more debate, more excavation, more play with this rich tradition, and the lively contemporary scene. Does the culture really exist if we aren’t arguing about it in cafes, in pubs and in print?

Which projects are currently keeping you busy when it comes to your own writing and academic work?

Well, too many to keep up with – and to imagine finishing any time soon. I’m working on a book of literary non-fiction essays in Gaelic, about Gaelic culture (in the broadest sense) and what it means to be a Gaelic speaker in the contemporary world. I will also hopefully finish a third book of poems next year, with the Mozart poem in it. And I’ll be delving into the murky waters of 19th century magazines and newspapers as part of a project to create an expanded sourcebook for the Scottish 19th century. Oh, and judging the Highland Book Prize, which is a real pleasure: books of any genre, connected with the ‘Highlands’ of Scotland one way or other – there are always great surprises.

The strategic partnership with Charles University is one way for St Andrews to retain and expand close cooperation with an institution on the Continent, even in the aftermath of Brexit. What, in your view, could be the main benefits of it for both universities? What would you like to see happening within the framework?

Post-Brexit there was the real risk of cultural and intellectual retrenchment in the UK, a turning inwards and depressed navel-gazing, with a celebration of dubious ‘British’ values and culture. This strategic partnership is a crucial bridge to avoid this, to keep ongoing links between such long-established, and friendly universities, and – I would hope – to raise different questions for each other, bring new perspectives, whether through research trips, joint conferences, student exchanges: there is really no limit to the kinds of joint thinking that can be done.

Apart from your substantial academic record and career in poetry, you also worked as a broadcaster and journalist for the BBC. What did you enjoy about it? Do you miss media work – or is it better just to give interviews to Czech media?

There was an immediacy and urgency to the journalism: responding to world events for a Gaelic audience (I spent weeks covering the war in Libya from a studio in Glasgow); telling stories from the Lowlands and the Highlands to a national audience, without resorting to exoticism; the excitement of the 10-second countdown before going live on TV. I miss all of those, and also the technical work of audio and film editing: I have little time for that in my day job now, and would love to get back into some filmmaking. But I am lucky enough to still be able to do a lot of enjoyable media work: contributing to programmes for BBC Radio 3 and Radio nan Gàidheal, and discussing literature on BBC Alba TV programmes, and – of course – talking to Czech media. It is always a pleasure. Thank you.

| Peter Mackay / Pàdraig MacAoidh, PhD. |

|

Peter Mackay / Pàdraig MacAoidh was born and brought up on the Isle of Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides in Scotland. He is a poet, broadcaster, journalist, and lecturer. As an academic, he has experience from a number of universities, including Queen’s University Belfast and Trinity College Dublin, and has also worked as a broadcast journalist and news producer for the BBC. He is the author of two monographs, Sorley MacLean (2010) and This Strange Loneliness: Heaney’s Wordsworth (2021), and two books of poetry, Gu Leòr / Galore (2015) and Nàdur De / Some Kind of (2020). In 2022–2023, he held the post of the official bard of An Comunn Gàidhealach [The Gaelic Association], one of the highest honours available in the world of Scottish Gaelic letters. His poems in Czech translation have recently appeared in the magazine PLAV (7/2023, svetovka.cz). |

| Petra Johana Poncarová,PhD |

|

Petra Johana Poncarová is a Marie Skłodowska-Curie postdoctoral fellow at the Department of Scottish Literature, University of Glasgow, and has been working mostly on modern writing in Scottish Gaelic. Her monograph Derick Thomson and the Gaelic Revival is forthcoming from the Edinburgh University Press. She is one of the co-directors of Ionad Eòghainn MhicLachlainn | National Centre for Gaelic Translation and translates directly from Gaelic into Czech, including the novel Deireadh an Fhoghair by Tormod Caimbeul (Konec podzimu, Argo, 2018). She was the manager of the 3rd World Congress of Scottish Literatures (Charles University, Prague, 2022). |

The strategic partnership between Charles University and the University of St Andrews was established in 2020 to support exchanges, joint projects, and other forms of cooperation. At the Faculty of Arts, some of the major outcomes so far have been related to the field of Scottish Studies. Support from the Strategic Partnership Fund has brought Robin MacKenzie and Peter Mackay to Prague and Petra Johana Poncarová to St Andrews; an upcoming special issue of the academic journal Litteraria Pragensia (litterariapragensia.ff.cuni.cz) on ecocriticism is being prepared as part of the exchange.

This article is also featured in print: Issue No. 12 of Forum magazine published in December 2023.