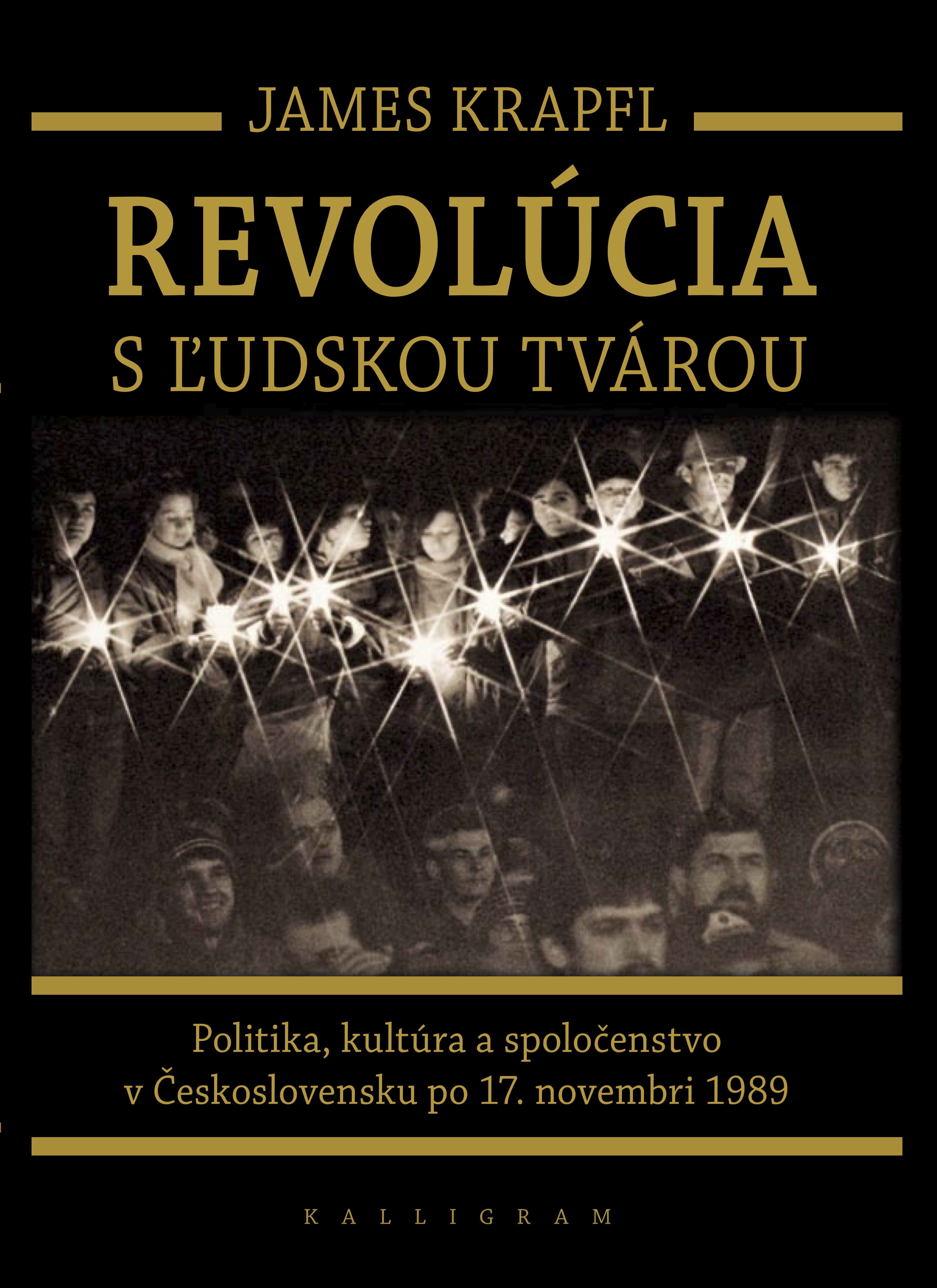

November 17 is Struggle for Freedom and Democracy Day, commemorating students and others who protested against the Nazi occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1939, as well as students 50 years later - in 1989 - who were savagely beaten by communist riot police. The infamous event sparked the Velvet Revolution that would bring down communism in Czechoslovakia. A revolution which Montreal-based historian James Krapfl says was distinctive in its appeal to humanity, humanness and non-violence.

Struggle for Freedom and Democracy Day - 17 November - is one of the most important dates and holidays in the Czech calendar.

Struggle for Freedom and Democracy Day - 17 November - is one of the most important dates and holidays in the Czech calendar.

Professor Krapfl is the author of the acclaimed Revolution with a Human Face: Politics, Culture and Community in Czechoslovakia, 1989-1992, originally published in Slovak by Kalligram and later in English by Cornell University Press. His cultural history notably shifts attention away from elites to citizens, many of whom had never expected the Iron Curtain to fall in their lifetimes, but came together in the heady days of the revolution.

In our interview on the eve of the 34th anniversary, Krapfl discussed the legacy of the Velvet Revolution, including his focus as a researcher and historian.

Forum: Is it fair to say that a cornerstone of your study was to put ‘ordinary people’ back at the centre of the story?

It would be better to say that my aim was to put citizens at the centre of the story. The concept of “ordinary people” is problematic, because on close inspection, no single person turns out to be entirely “ordinary.” By focusing on “citizens”—all 15 million of them—I could take into account their real diversity rather than privileging some ideal, average type. If you recall the language of the time, moreover, you remember that it placed great emphasis on the word občan, or citizen, in what amounted to a collective rediscovery of civic agency. The name of the largest political association to emerge in 1989, Občanské fórum (OF), or Civic Forum, was simply the most vivid of many examples.

So they were a starting point... and the reason? Had their story been sidelined?

The reason was simply that democracy cannot exist without participation of the demos. The democratisation literature of the 1990s largely ignored citizens, as if the establishment of democracy were merely a matter of revising constitutions, reforming institutions, and holding elections—a very top-down perspective. Early histories of the revolutionary transformations of 1989—not just in Czechoslovakia—likewise tended to focus on “leaders” and other elites, whether revolutionary, Communist, or international, reducing the millions of mobilised citizens to colourful window-dressing.

Based on my own experience of participating in democracy in America—not to mention Tocqueville’s perceptive account of the phenomenon—such approaches seemed collectively short-sighted. Because such scholarship on democratisation informed policy, it was no wonder that we ended up with such disasters as the top-down attempt to establish democracy in Iraq at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Because Czechoslovak citizens had successfully established democracy—not just at the state level, but locally— I wanted to show how they did it.

Those of us who were old enough remember seeing the reports about the crowds swelling from first tens to hundreds of thousands in the pro-democracy demonstrations on the country’s main squares recall it was precisely those masses that shook the Communist regime to the core. Likewise, it was a brutal crackdown by the regime on a peaceful student demonstration in the first place which was the spark… Is it easier to push some narratives rather than the story of 15 million people?

I would say it has to do with interpreters’ conceptual schemes—how they’re equipped to perceive reality—and specifically with where they perceive agency to lie. If you believe that the most important decisions are usually made by an elite, that’s the social group you’ll privilege in accounting for historical change, especially in the short term. It’s also common to believe that impersonal structures constrain our decision-making to the extent that it’s less important to speak of human agency than of these structures. Marxist interpretations of history often fall into this category. Of course, impersonal structures and powerful individuals often do play decisive roles in history, but it is wrong to suppose that “ordinary” people do not. Particularly in revolutions and other times of collective effervescence, when leaders are themselves often following the crowd, it is a mistake to ignore popular agency. The institution of democracy assumes, moreover, that every citizen possesses agency, and if our historical interpretations are not to subvert democracy, they must acknowledge the agency of each citizen.

Unfortunately, interpretations of the revolutionary events of 1989 and subsequent European history have tended toward a certain elitism. This is true not just in scholarship, but also in the popular media, even in the Czech and Slovak Republics. For nearly a decade now, we’ve been paying the price with a populist backlash. Of course, it is more difficult and time-consuming to study the agency of a large number of people than just a handful, but if we want to cultivate responsible citizenship, we need histories in which citizens can recognise themselves.

Czechs commemorate the Velvet Revolution with a symbolic "89" tram. Normally, there isn't any such tram in the transport grid.

Your book covers the period from 1989 to 1992 – a series of pivotal and quickly shifting events. At what point, if any, were the ‘ideals’ of the Velvet Revolution at their ‘purest’ or most focused?

Those who participated in the revolution experienced the period of the student strikes—from 18 November 1989 to 3 January 1990—as transcendent. Participants described a time of miracles, rebirth, or resurrection, a time outside of time, or what anthropologists call a liminal period, which in this case can also be described sociologically as a period of collective effervescence. As I show in the book, the events of 17 November can be compared with the Big Bang, for they gave rise to an expanding universe of signifiers. Consciousness shifted, people acquired a new sense of what was meaningful, and as a Slovak journalist wrote, “suddenly we all want to assemble as much as possible, to listen as much as possible, and to speak as much as possible.” In doing so, citizens collectively produced new symbols to represent their newfound sense of community, and they collectively articulated the ideals of what they explicitly called “a new society.”

These ideals were constantly being developed and refined, but during these weeks they exhibited a remarkable coherence, and there was also remarkable agreement about most of them. There was no single document that encapsulated them all, but by studying the thousands upon thousands of documents that citizens themselves produced in November and December 1989, it is possible to recognise the ideals that gave them coherence and united those who signed them.

What were some of the outcomes or directions that hung in the balance in the early days of the revolution? Aside from the very real possibility of a violent crackdown by the regime, there were questions of who would come to power and, later, political directions the country would pursue. There was Havel’s third way, etc.

In my view, “the early days of the revolution” include the entire period from 17 November to 3 January, since the revolutionary process was by no means over then. People still spoke of “completing” the revolution in the early 1990s, and I would say that the process of reconstitution that began in November 1989 continued until 2004, when the Czech and Slovak Republics joined the European Union. We might compare the American revolution, which began in 1774 but arguably lasted until the ratification of the federal Constitution in 1789.

The famous plaque on Prague's Narodni Ave.commemorating student protestors who were victims of a brutal police crackdown in November '89.

In the early days, then, some of the key questions included whether and how workers would support the students by participating in the General Strike, how the party and government would react, and the form that the civic movements would take. Initially, for example, local civic associations in Slovakia were more likely to call themselves civic fora than branches of Public against Violence, and it wasn’t until the end of November that it was decided, from above, not from below, that Civic Forum would be Czech while Public against Violence (Verejnosť proti násiliu, or VPN) would be Slovak. It was, however, crucial that there was a united opposition—unlike in East Germany, where several opposition groups emerged in the autumn of 1989 and they remained independent, limiting their impact.

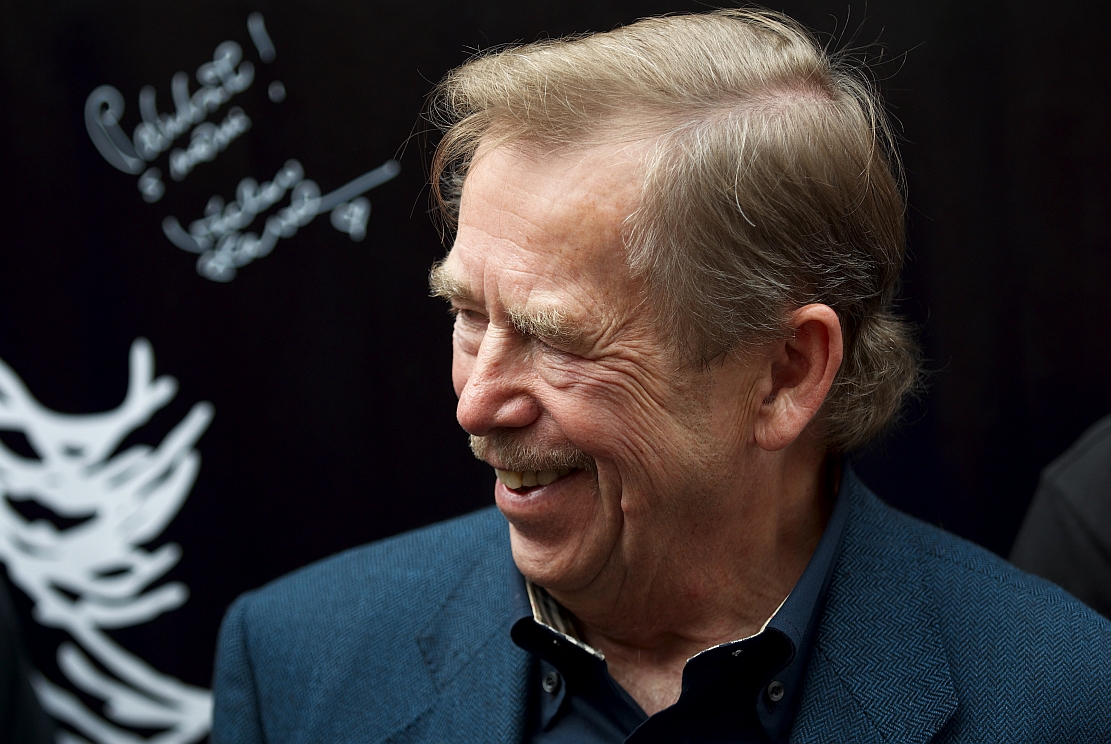

After the General Strike revealed the extent of popular opposition to Czechoslovakia’s Communist regime and citizens made clear their desire for a government with a non-Communist majority, another key question was whether the civic associations would nominate people to fill ministerial positions. Again, the comparison with East Germany is instructive, for there the opposition refused to take power, and the result was that the state collapsed and had to be incorporated into West Germany on terms that the West could essentially dictate. An important question arising immediately after the ministerial one was whether Alexander Dubček would become president with the economist Valtr Komárek as prime minister— which was the combination first proposed at public meetings and would have signified some continuity with the reform movement of 1968—or whether it would be Václav Havel with the acting prime minister, Marián Čalfa, continuing in that role.

Starting in early December, citizens also began trying to democratise their workplaces—in accordance with existing laws that allowed them, for instance, to dismiss their directors through votes of no confidence. Continuing into 1990, a crucial question for most working men and women was whether this movement would prove successful. The fact that it became less so over time resulted in one of the most divisive political questions of 1990.

Czechoslovakia's first post-communist era president Václav Havel. The playwright and dissident's rise symbolised new beginnings for many.

Did you yourself have previous ties – or roots - to Czechoslovakia? I read that you had lived here in the nineties… what was that experience like for you as a westerner?

My family’s roots are in central Europe, though not in the lands that became Czechoslovakia. Nonetheless, when I first arrived there in September 1992, I experienced less culture shock than when I had moved from Iowa to California to attend Stanford University. The first two weeks were difficult, of course, knowing only the rudimentary Czech I had managed to teach myself over the previous summer—at a time when very few people spoke English — but very quickly I felt at home. It helped that the climate, food, and some cultural patterns were similar to those I had grown up with — my Bavarian and Tyrolean ancestors having themselves sought a similar climate and passed down their cuisine and habits—but there was also something specifically Czechoslovak that made me feel at home. It’s difficult to say exactly what it was—perhaps a combination of sincerity, creativity, a distinctive sense of humour, a playful curiosity, a certain down-to-earthness. In any case, I felt I could relax.

Olomouc and Trenčín, where you lived at different points, are smaller towns – that in itself must have been very different from the experience of many expats who came here at first, who gravitated to the larger cities, Prague, Brno…

I spent some time in Prague as well—having spent the first half of my study-abroad semester in 1992 at Charles University before moving to Olomouc for the second half, and I came to Prague again for two Czech-language summer schools at Charles, but I chose to return to Olomouc when I received a Fulbright scholarship in 1996, in part because it was easier to meet people and improve my Czech there. To understand what life is like for most Czechs and Slovaks, moreover, it’s necessary to live outside the capitals, which are more exceptional than emblematic.

At that time, were you already gathering ideas concerning the political, social, economic transformation that had been set in motion?

The questions and hypotheses that motivated my study came to me already in 1989, when I was a college freshman enrolled in a year-long seminar marking the bicentennial of the French Revolution, where we studied the French experience in the fall of 1989 and the comparative history of subsequent revolutions in the spring of 1990. Observing unfolding revolutions while immersed in the comparative, theoretical study of revolutions, it was impossible not to formulate hypotheses and research questions—questions that, as time went on, I was surprised to find that no one else was asking. When I came to Czechoslovakia in 1992, when I returned for the summer schools in 1995 and 1996, and when I came on the Fulbright from 1996 to 1998, I was constantly gathering information to answer the questions I had started posing in 1989 and 1990—and of course asking new questions the more I learned.

They proved useful later?

They proved useful immediately: in the research paper I wrote at the end of the 1992 semester, part of which I incorporated into the M.A. thesis on Czechoslovakia’s revolution that I completed at the CEU in 1999, though that was based mostly on my Fulbright research. All this work eventually found its way into my doctoral dissertation at UC Berkeley and the book Revolution with a Human Face, though they were of course based on considerably more research than what I had done in the nineties.

I suppose things were still quite fresh then and that the dust hadn’t ‘settled…

There was still a revolutionary atmosphere in 1992—the fate of the federation was in question, after all—and among my peers at Charles and Palacký universities there was a tremendous excitement about the future. “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” as Wordsworth wrote. By the later nineties the sense of what Lynn Hunt calls a “mythic present” had abated, though the revolutionary process was still working itself out. I was fortunate to able to “breathe in” the atmosphere surrounding the Czech and Slovak elections of 1998, the Děkujeme, odejděte (Thank you, now leave) movement of 1999, accession to the EU, and so on. For a historian, at least, an exciting thing about central Europe is that history is always happening.

Young people often mark 17 November with their parents and siblings in Prague or other major cities around the country including Brno, pictured.

As a social historian, what were specific elements that formed the backbone of your book?

I identify myself more as a cultural historian, in that what interests me most is the history of the webs of meaning that are culture in the broadest sense. I’ve already explained when I “picked up the thread” and began researching, but I could add that it was while I was based in Olomouc in 1996 that I discovered the revolutionary flyers or letáky that had been such an important medium for the formation of public opinion in 1989. A student at Palacký University told me about them, and on a visit to Opava I discovered that the district archive there had a collection. I then started systematically visiting archives, mostly in Moravia and Silesia, but some in Bohemia, to study and wherever possible photocopy these materials.

Some former student strikers even shared their collections with me. I also discovered student and local Civic Forum bulletins through this method. By the time I started my M.A. in Budapest I had roughly 2,000 documents, which allowed me to chart almost from day to day how citizens’ thinking changed. When I conducted the research for my doctoral dissertation in 2004-05, I supplemented my earlier research with visits to archives across Slovakia and Bohemia, together with a few in Moravia I had previously missed. I also gained access to the very rich archives of the coordinating centres of Civic Forum and Public against Violence in Prague and Bratislava.

How did the archives differ, how would you describe them?

The key difference for me lay in how much material the different archives had. The central OF and VPN archives had more than I could get through, though I studied the majority of their holdings and that was enough to establish clear patterns. Some district archives, like those in Olomouc, Louny, or Považská Bystrica, had such extensive collections that I could rely on them alone to demonstrate certain patterns. Others had perhaps only a slim folder. Always the visit was worthwhile, however.

Václav Havel and US President George Bush in 1990.

What other kinds of documents did you find?

I’ve already mentioned the flyers, which students were chiefly responsible for typing and duplicating in November and December, travelling across the country to distribute them. They would be posted on walls and shop windows, around which people would gather to read them, often getting into impromptu discussions with strangers.

Students also published bulletins; in Olomouc, for example, they originally appeared daily, then they became weeklies, and they continued to the end of the academic year. At other universities their duration was longer or shorter. Local Civic Fora and VPN branches soon started publishing them, too, and in Slovakia they often metamorphosed into weekly newspapers. Especially in the coordinating centre archives I found an absolutely fabulous genre of revolutionary writing: the proclamations that workplace collectives and other groups drafted (mostly in November and December, sometimes later) and sent to the coordinating centres in addition to local posting. There are thousands and thousands of these, and I know that volunteers of the Bratislava coordinating committee counted all the signatures and were therefore able to conclude that they had the support of a majority of Slovakia’s workforce. In some archives I found videotapes of happenings or public meetings, and these were invaluable; they make the emotions of the time visible.

Oral history is another key component – how important was it for you to speak to people about how they viewed the revolution – what they felt at the time and how things tuned out?

When I started the Fulbright, I initially relied mostly on oral history, but I quickly found it both time-consuming and very hit-or-miss with regard to getting useful information. Already by that point people often had “canned narratives” that I lacked the knowledge necessary to circumvent. When I discovered what rich sources lay in archives, I switched completely to reliance on them, since documents from a particular point in time don’t change the way memory does. I still used oral history occasionally, but only to supplement material from the documents, with which I could confront informants to stir specific memories. That said, I constantly spoke informally with everyone who wanted to speak (usually whenever anyone discovered I was a foreigner and asked the reason for my presence), and this evidence definitely shaped my thinking.

You have spoken about the language and ideals of the early days as being ‘romantic’. But I guess an unprecedented moment like 1989, with hope for a better world, was romantic by its very nature? Especially for young people who saw hope where there hadn’t been any before and were driving across the country to connect and get the word out, making posters at faculties at night and so on….

The romantic frame posits a world where extraordinary things can happen, where actors are capable of heroic deeds, and where one side in the struggle that motivates action is clearly good. The violence of 17 November established a clear difference between non-violence and violence, good and evil—and it was itself out of the ordinary experience of most participants, as well as of those who heard about it. For those shaken by this violence into taking action, the romantic frame was the natural way to make sense of the situation. It reflected a newfound sense of meaningfulness.

What followed the romantic way of seeing things?

It’s worth noting, first of all, that the students’ romantic interpretation of the events of 17 November—good against evil—competed initially with the regime’s interpretation, which we can identify as ironic, wherein the students and other “elements” had disrupted public order and attacked the police. In the war of narratives that ensued, it was crucial though by no means a foregone conclusion that most of the public came to accept the students’ framing. As I explain in the book, Havel and other prominent figures began after the General Strike to offer a comedic narrative—a framing that posited only the ordinary degree of human agency and therefore lent itself to less radical, perhaps more practical programs, in which the Communists could be partners. Many of those who remained committed to the transcendent vision of a “new society” that had seemed so possible in November and December, however, eventually came to interpret unfolding history through the framework of tragedy, asking what mistakes resulted in failure to achieve goals that had seemed desirable and achievable. Thus it was that some Czech students on the first anniversary proclaimed that the revolution had been “stolen.” Finally, some came to question whether what had happened possessed any meaning whatsoever, or if they had all just been silly or misled, and they interpreted the revolution (or non-revolution) through the frameworks of irony and satire.

When things cooled and Civic Forum splintered into different political directions and factions - was that a point when people became disillusioned?

It was because of disillusionment that Civic Forum and Public against Violence splintered. I’ve already mentioned that the decision not to recognize local Slovak civic fora came from above—specifically from the coordinating centres in Bratislava and Prague. Later there were more and more instances where local activists in both the Czech and Slovak republics came to feel that their colleagues in the capitals were making decisions about them without them. One example was the electoral law, which established a proportional system without any consultation with the public, which it seems inclined toward a majoritarian or mixed system. Local activists had to fight hard to get representation in the civic associations’ central decision-making bodies, and it came only grudgingly. These volunteers were further incensed when the candidate lists for the June 1990 elections were formulated without taking their proposals seriously, and when central organs dismissed district-level complaints in the spring and summer about the often tense situations in workplaces where democratization efforts had not succeeded—arguably because central figures in January had told citizens to halt them. The result was the revolt of district-level activists in OF and VPN against the coordinating centres in the autumn of 1990, resulting in their internal splits in 1991.

I guess it would be only natural for divisions that earlier would have been smoothed over or less apparent or important to come to the fore…

Some divisions were old and, as you suggest, had not been apparent. Others were new. An old one concerned explanations for the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968—whether blame lay primarily with foreign powers or with the reform movement itself. Among the ideals that citizens widely expressed in November and December 1989, one was for a reformed socialism, and it was the only ideal about which significant disagreement was expressed at the time. To some extent the disagreement was correlated with interpretations of what had happened in 1968, though obviously this was not a question that could be debated publicly during the decades of normalization, and so the cleavage became only slowly apparent in 1989. Most other cleavages were new, however, emerging only in the course of the revolutionary process, even if one can sometimes discern antecedents.

What is the dominant myth about the Velvet Revolution that you reject?

Perhaps the worst myth is that the revolution was just an instant, or that it ended with Havel becoming president at the end of December. One of the greatest tragedies of the revolution was that many people thought it was over when really it was just beginning. Revolutions are not just about the demise of an old regime; more importantly they’re about the reconstitution of society and the institutions that represent it. This process necessarily takes years. By thinking at the beginning of 1990 that victory was assured and that it was safe to leave the public sphere and focus on enjoying newfound freedom, many people discovered to their dismay that crucial decisions ended up being made without their input. It’s also important for us today to remember how complex and uncertain the time of revolution was. Reducing it to an instant, as the annual commemorations in Prague now tend to do, contributes to the erasure of individual citizens from the history of the revolution. It’s important to remember the choices they faced at the time, how they overcame divisions within society, how they struggled to create a democratic society from below. Only thus can the experience inform our decision-making in the present.

Another pernicious myth is that the revolution aimed to establish liberal democracy as we know it now, or even that it was a conservative or “rectifying” revolution, as Jürgen Habermas called it. The outcome was not clear or even necessarily implicit in the beginning, and neither today’s Right nor Left should lay exclusive claim to it. This is a much greater problem in Slovakia than in the Czech Republic, but it’s important to remember that the revolution united everyone who thought it should be possible to govern without violence, who wanted a society for people, rather than for bureaucratic systems.

What were dominant aspects of this particular revolution – coming from the people – that set it apart or made it unusual? Are they what you call the ideals of November? You cite non-violence as one, as well as its very humanness… were these qualities of Czechoslovak society that are remarkable? They defined not only the revolution but also the ‘amicable’ Velvet Divorce… as well as the country’s hopes for a milder, more humane regime twenty years earlier in the Prague Spring.

Logically the most central ideal of the revolution was lidskost/ľudskosť, which can be translated as humanness or humaneness, depending on the context. Other revolutionary ideals were justified with reference to this one. In the “new society;” citizens and institutions would respect individuals’ human dignity, they would not be reduced to their roles in some system, to borrow language from Havel’s essay “The Power of the Powerless.” As electricians from a Stonava mine wrote, “We believe that the era of manipulation with human opinions is finally at an end, and now workers will be able not just to work, but also to feel, to believe, and to think.” Non-violence was a closely related ideal, meaning rejection not just of physical violence, but violence in all its forms, including psychological, economic, and environmental violence.

In my book, I argue that Czechoslovak thinking about human dignity and violence in 1989 was innovative in comparison with earlier revolutions in European history, even though the ideas have always figured in revolutions. First, Czechs and Slovaks elevated humanness and human dignity above ideology, insisting on not losing sight of human reality regardless of what rules, procedures, or other man-made systems might dictate. Second, in situating itself against violence as such, rather than approving one kind of violence in order to combat another form, the Czechoslovak revolution went further than previous revolutions in getting to the heart of the problem that has bedevilled human society from time immemorial: our own violence, and the way we use violence to create and maintain meaning.

It is worth noting that citizens in the revolution also articulated an innovative vision of blending representative and direct democracy, political and economic democracy. Some of their ideas, like procedures for holding referenda or sizable student representation in academic senates, came to be realized, while others eventually fell by the wayside. It was remarkable, moreover, that citizens who joined the revolutionary movement from the very beginning emphasized democratic practice, creating in their local milieux a culture of democracy that remains recognisable today.

A Million Moments for Democracy organised numerous protests just a few years ago voicing opposition to the then-government of Andrej Babiš.

Where is this tradition found today? People became disillusioned with the politics of Klaus and Zeman, populism saw a rise here, but there was a germ of it in the election of a new president this year. For a moment, crowds appeared on the squares in the name of returning dignity to Prague Castle and it seemed that a similar kind of energy was briefly tapped…

Indeed, the practices of 1989 have become part of Czechs’ political-cultural repertoire. And this is a great thing. When American friends of mine happened to be visiting Prague at the same time when a Million Moments for Democracy demonstration was planned, I told them they should attend, and they reported amazement at how orderly, creative, and dignified it was—that people could attend with babies in prams—very unlike demonstrations in the United States. This cultural heritage is another reason why the revolution in all its complexity should be recalled, rather than reducing it to a moment.

You’ve mentioned that you studied at Charles University several times in the 1990s; have you had any more recent affiliation?

From 2019 to 2021 I was part of a research team in the Faculty of Humanities. My colleagues were historical sociologists interested in the Revolutions of Dignity that swept the Arab world in 2011; I helped to develop new theoretical frameworks for thinking about revolutions of dignity in the modern world. The concept of human dignity as a revolutionary aim appeared at least as early as in 1789 in France. It came up again in Poland in 1980 with Solidarity, I’ve argued that it was the central ideal of the Czechoslovak revolution of 1989, and after the Arab Spring, there was Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity ten years ago and a Belarusian attempt at the same in 2020. The idea of human dignity is becoming steadily more prominent in revolutions, and I’m interested in why that is the case and where we might be going.

Currently, I am also working with Charles University’s own publishing house, Karolinum Press, to bring out a revised and expanded edition of my book in Czech.

How do you feel when you return to the CR to see how it is doing and experience the country again?

Last year I was in the Czech Republic on sabbatical, and I was indeed very happy. The same cultural qualities that I found welcoming in 1992 were still there, and I felt just as much at home.

| Associate Professor James Krapfl |

| James Krapfl is an associate professor of European history at McGill University in Montreal. He is a specialist on the history of political culture. His first book, Revolution with a Human Face: Politics, Culture, and Community in Czechoslovakia, 1989-1992, won the George Blażyca Prize in East European Studies from the British Association for Slavonic & East European Studies, as well as the Czechoslovak Studies Association Book Prize. With Barbara J. Falk he recently edited a special issue of East European Politics and Societies to mark the fortieth anniversary of Václav Havel’s essay The Power of the Powerless; in connection with this effort Krapfl received the Michael Henry Heim Prize in Collegial Translation. Professor Krapfl has been a visiting scholar at the Institute for Contemporary History in Prague, the Historical and Sociological Institutes in Bratislava, and Palacký University in Olomouc. He earned his Ph.D. from the University of California, Berkeley, following an M.A. at the Central European University in Budapest. |

Look back at our special issue marking the 30th anniversary of the Velvet Revolution four years ago here.