One thing that most foreign students do when they begin their studies at Charles University is immerse themselves in the local culture - from the arts and live events to seeing historic sites and getting to know the pub scene and more. But another way to learn about local culture, not suprisingly, is through literature.

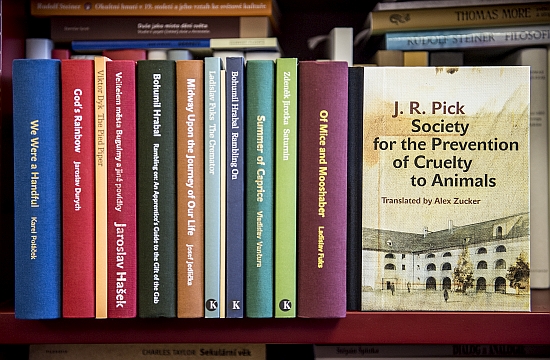

Luckily for English-speakers, for more than 15 years the university’s Karolinum Press has been publishing a series called Modern Czech Classics, which has proven immensely popular, not just in the Czech Republic but worldwide. The series has especially been appreciated by countless readers as well as students of Czech Studies, featuring some of the country’s best writing as well as lesser-known gems.

15 min. 37 sec.

Recently I met with Karolinum Press editor Martin Janeček to talk about the series and find out how it all began.

“It began under the leadership of Dr. Jaroslav Jirsa who played a great cultural role within the Prague literary scene. He got the idea to publish the comedic novel Saturnin by Zdeněk Jirotka in English. Back then it was considered ‘only’ a humorous novel but since it has grown in stature, and is now widely considered a classic. It was voted one of the books of the century and a book close to readers' hearts in two popular contests. In short, it was not as well known back then as it is today. In reality, the first one was just a test case to see how well we could publish a translated works of fiction.”

Who was the intended audience?

“That sort of came later. The impetus for the translation came from a translator at the Faculty of Arts and it was only after a few years that we realized that we could keep doing this. That was when they faced more principle or key questions and it was decided that the list of books that could be published would include not only light humour but also more challenging works of fiction, like Vladislav Vančura’s Rozmarné léto (Summer of Caprice or Capricious Summer).

“That had been widely considered impossible to translate – it is typical Czech humour only Czechs are supposed to ‘understand’ - which is widely debatable. We wanted to challenge this common cliché that some things only exist to be understood in Czech. We wanted to tackle the notion that you had to be born and bred here to appreciate these novels fully. That, in the end, is the basis for the series.

“The series began to take off and really came together after a number of years of searching, when we found a very good distributor, which is the University of Chicago Press. That meant we were no longer focusing on just Prague but international distribution. The step up required a lot of planning in advance and raising a lot of information and it meant a great opportunity also for academic books that we also publish in English and are our primary focus.

“From that point on, we could really begin focusing on something like an English-language program, which represents around 15-20 percent of our output or production today. So went to that from what was initially trial-and-error. Now there are new agenda which none of it would have started had it not been for Jirsa and the first translator. This side-project ironically opened the door for our main activities, bringing us access to world markets.”

Classic literature really can open a window into a country’s soul and can help readers abroad understand this part of Central Europe. When I was growing up in Canada there wasn’t that much on the shelves there beyond Jaroslav Hašek and Kafka (although it's important to point out that he of course wrote in German)…

“Nonetheless Kafka was fully a part of Czech culture…”

Of course. But there wasn’t much more in the late 1980s on bookshelves in Canada - not like today. Many of the titles you are putting out have gone a long way in broadening what’s on offer. And that is valuable. You mentioned Summer of Caprice that was also made into a famous film by Jiří Menzel. What are some of the other titles in the series?

“The series really developed into a great communication tool and thank you for mentioning the Menzel film because film is another facet of all of this. We have worked closely with professors and experts of Czech Studies and Czech literature and today we work with experts worldwide and film has been an important part of that for decades, ever since the Czech New Wave in the 1960s.

“In film, you have Capricious Summer and Closely Watched Trains and The Shop on Main Street which is our next release. The series is not necessarily aimed at being the very ‘best of Czech literature’ but adaptations of classics and important writing to also attract and teach new international students. That is part of the aim as well. We are very happy that we cooperate with foreign schools, who provide us with suggestions on what could be translated and sometimes they too have translation competitions and play an active role. Spreading knowledge and Czech culture internationally is the aim and we are glad that foreign scholars are also on board.”

When it comes to translating you really have to have a deep talent for it and a sixth sense for both languages… I know that you work with many of the same translators, so you know their style. Nevertheless, it must be interesting when you get something on the page and it ‘pops’ – yet it has the same feeling as the original…

“To me, literature is a dialogue and producing literature is also a dialogue and in the case of translation even more so because there is no one single way to translate something. Literature – fiction – is a very complex set of issues and contents. It is more than just linguistics but a cultural communication issue and a good translator has to be a very good writer in his or her target language. We start with a sample and some trials… of course when we work with stars like David Short or Alex Zucker we know how they translate but even as professionals they are happy for any input or a second opinion. It’s one thing for the book to exist in published form but later it will exist in the reader’s head and getting there is a long process.”

Would you say that interest in translating Czech into English has grown?

“I would say so and I would add an offshoot that an interest in translation studies itself has grown. When we started, less than one percent of global works was translated into English. About 10 years ago, at the University of Rochester, they started a foundation called Three Percent, which aimed at boosting the number of translation into English and to get to three percent. Today, this foundation is funded by Amazon and translation has become very popular; there are new awards and more recognition in print and online media. English is dominant but also flexible. There is a growing interest is smaller or lesser-known cultures being translated.”

To come back to specific works, when I was working in radio I used to hear regularly from a kind of expert on Švejk in the United States who had a new translation of The Good Soldier Švejk and argued that the famous translation by the diplomat Cecil Parrott was dated or old-fashioned. To your knowledge, is anyone else looking into a new translation of the famous work by Hašek?

“I have to be careful here not to disclose too much as we have certain plans of our own which are too early to reveal. Parrott’s translation, first published I think in ’63 and still published by Penguin Classics, is still available but I would agree in principle that most classical works require – after some time – new interpretations. Things change: not just the language but translation studies too.

“Not surprisingly the new German translation of Schweik saw the book become a bestseller. Not only did it sell well but it is a new interpretation. Based on the older translation, many Germans saw Schweik solely as a comic figure or humorous novel or even as a caricature in Brecht’s cabaret style.

“But there has always been so much more to Hašek, rather Kafkaesque or absurd, and that has come a little into the foreground. So I think the new interpretation after almost 100 years brought new life to Schweik in German. And this book is such a flagship that its success helps Czech culture as a whole.”

So translations themselves have a certain shelf life or half-life…

“Yes, I would say so.”

So should I ask if there is a 'great white whale of a novel' you are pursuing?

“There is one that a publication date is looming for and that is Ladislav Vaculík’s Czech Dream Book. The English translation itself has an interesting history. It was commissioned by Random House, one of the big five American or international corporations in publishing and it was a great opportunity for Vaculík to become rich and famous. But the author declined the contract because he was not happy with the role the publisher assigned to the translator. As a translator himself, who had been in the underground with the Petlice series, he turned the publisher down. It was an admirable move but meant that the English reader had to wait until, hopefully, next year.”

We have been talking about the Modern Czech Classics series. Saturnin has different graphics and illustrations by the late Adolf Born but the rest has a unified look.

“The decision for the overall look was taken in the pre-digital era and we had a choice of either going with paperback or with a high-end look on quality paper with a sort of gift wrapping. And the latter option helped cover translation costs. This series is independent and is not funded by the university.

“So we opted for special binding, with illustrations which is not common in books for adult readers, so that is special. In the digital era, and we too are digitising, it has the added value of something you can look at again and again and feel in your hands and examine while reading. That too is part of the overall package and experience.”