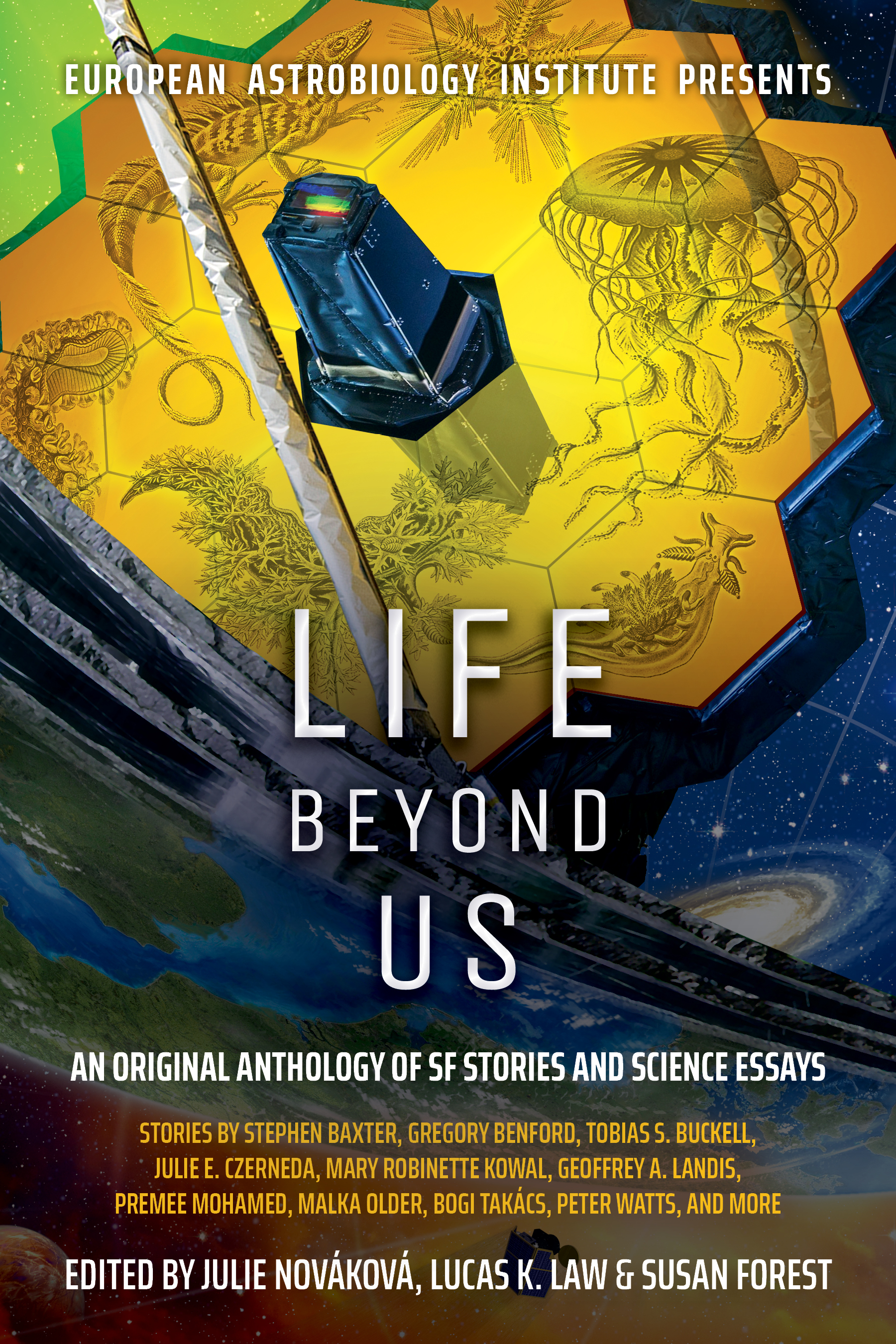

“Have you ever imagined what life would be like if it evolved in a cold ocean beneath an impenetrable shell of ice, or on a world whose haze obscured any view of the universe beyond?” That is a question posed by a new crowdfunding campaign launched by members of the European Astrobiology Institute, to publish an exciting new anthology of new science fiction stories by both up-and-coming and world renowned authors, including Mary Robinette Kowal, Stephen Baxter, and Peter Watts. The editor of the anthology, Julie Nováková, an established sci fi author, biologist, and a PhD student at Charles University, told Forum more not only about the book but the importance of science popularisation and outreach.

Science fiction is a big part of your life: how would you describe its importance?

For me, science fiction is both good entertainment and a sandbox for new ideas, for exploring certain ways that technology – as well as new scientific discoveries – could change our world. As an editor, as well as a reader, I love seeking out stories that do something interesting with this, that imagine the “what ifs” that are central to the genre of science fiction. For example, what if we colonized Mars and only then discovered traces of local life that had once existed or still did. That raises ethical questions as well as has a potential impact on society. We can explore scientific, societal and technological aspects, and this is what I love about science fiction most: the way it allows us to imagine different worlds that could potentially become our reality and different things that could exist.

It has been called the “literature of ideas” and when it comes to accuracy we’ve had all kinds of experience in the past, some stories more accurate than others – but always stimulating. One of the kind of classic examples is “Where are the flying cars ?” which were envisioned in a lot of pulp sci-fi in the 1930s… But on the whole, a lot of it has also been fairly accurate.

I agree. We can see quite realistically imagined space travel in science fiction already in the early 20th century. After all, the father of rocket science, Konstantin Tsiolkovsky, also wrote science fiction stories and novels. Other authors, such as Arthur C. Clarke, wrote about using geostationary satellites for worldwide communication back in the 1940s – before spaceflight had even begun. So that is a pretty good track record.

But I would also like to add that it is not the aim of science fiction to simply predict the future: I think that the strength of science fiction lies precisely in extrapolating how different developments would impact our civilisation and humankind. That doesn’t necessarily have to be realistic: there are wonderful science fiction – or fantasy – books which are very relevant, but not very realistic. Nevertheless, the stories in the planned anthology, Life Beyond Us, in general get the science right. Not necessarily completely, but at least the basic points.

Inspiration and outreach

One of the aims of the crowdfunding campaign and the publication of the anthology is to serve as a popularisation tool. Tell me about the institution behind the project.

The European Astrobiology Institute (EAI) was founded in May 2019, almost exactly two years ago, and it is a conglomerate of mostly European institutions: research institutes, universities, and agencies, that aim to facilitate research in astrobiology and to support science education and outreach. Several summer schools and conferences had been planned but, unfortunately, the pandemic in early 2020 limited us to largely virtual events.

There are biweekly seminars by EAI scientists available on youtube that can be useful for students and members of the general public who are looking for more in-depth information, where you can see discussion of topics such as planetary formation and biosignatures. Our focus on science popularisation last year also led to a free e-book of science fiction and essays we called Strangest of All. Next year we hope the situation will have improved and we will be able to offer summer schools and other events and conferences in person, but we’ll see.

Speaking of online, last year you gave a talk about the roots of science fiction and how far back they go, and while most of us would pinpoint the start of science fiction as late 19th/early 20th century, the core question “What is out there?” far precedes that.

Of course. You have elements of science fiction in ancient myths and legends. We have stories such as The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter from 10th century Japan, which features a moon princess who comes down to Earth before eventually returning home to her people. The Moon is the centre of many of these tales and legends, because it has been with us since the beginning of history and plays an important role in mythology. But some cultures imagined that there might be life on different worlds farther away. Later on, in the Renaissance, we got a boom of what might be called pre-science fiction. Somnium, a novel by Johannes Kepler, was published posthumously; apart from the fact that we now know that the moon is incapable of supporting life, the astronomical depictions were actually pretty accurate, at least for Kepler’s time.

Modern science fiction, though, got its start in the early 19th century with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein that is still a prime example of how science fiction can help us imagine the impact of science on society and individuals and especially unintended consequences. That shows that we have to tread carefully. Later, you have Jules Verne and H. G. Wells and authors in the late 20th and early 21st century to get to where we are today.

Another aspect that is notable is just how inspiring science fiction can be, from someone taking science classes at school to visionaries like Elon Musk.

Today’s entrepreneurs like Musk or Jeff Bezos have repeatedly mentioned how inspired they were by science fiction as kids and adolescents, that it provided a vision of venturing beyond Earth and focusing on space flight and space research in a way that they would not find elsewhere.

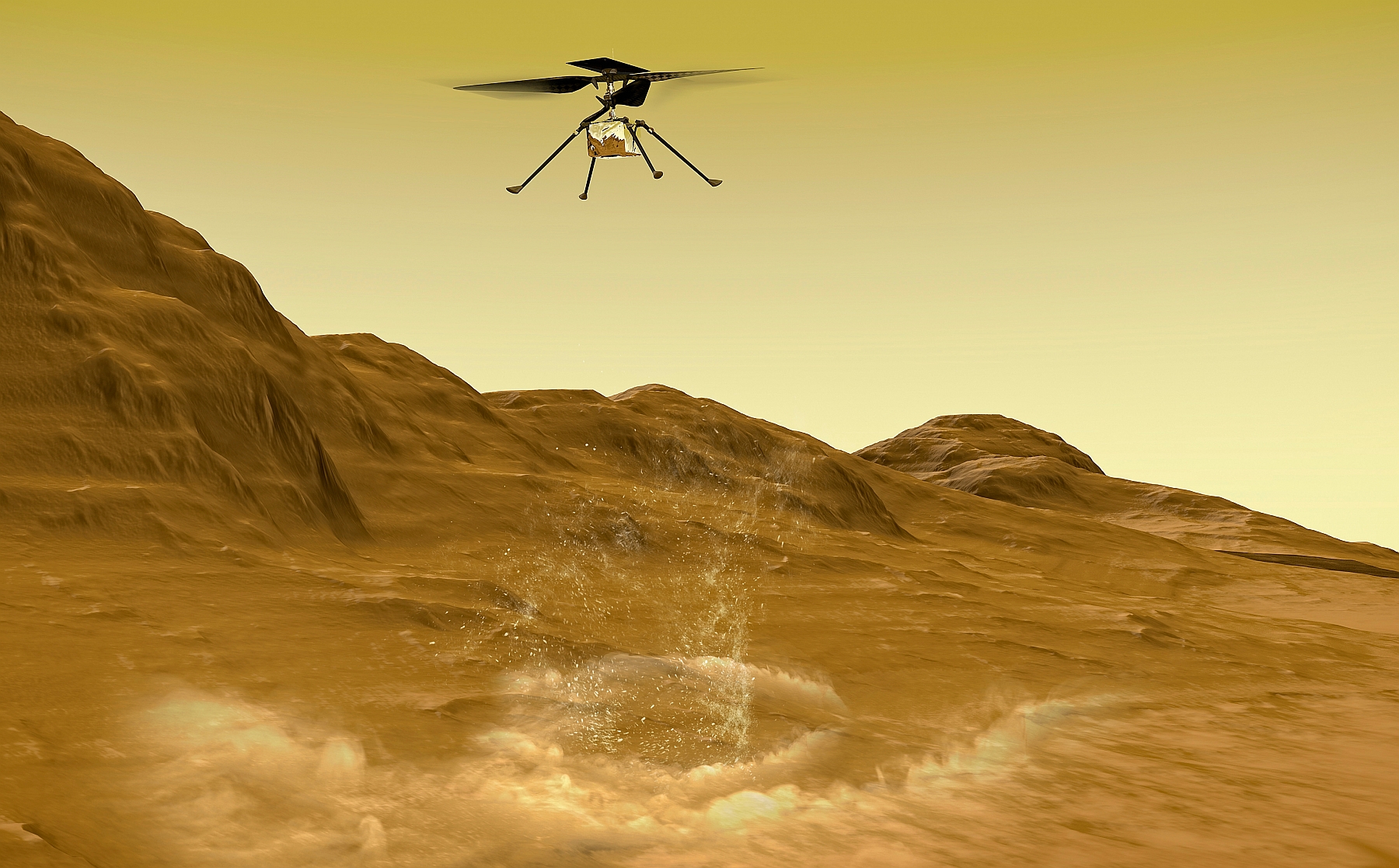

The popularity of astrobiology

You mentioned the pandemic we have all experienced: it has been a very tough period but at the same time one of the things that has been uplifting are ongoing advances in science: whether we are talking about the successful landing of the most advanced rover ever, Perseverance, on Mars, ot is helicopter. It is due to fly in what has been described as a “Wright Brothers moment” any day now. Then, there was the launch of Space X’s manned rocket to the ISS last year, and scientists are discovering more and more exoplanets all the time some of which could have theoretically have conditions appropriate for life. In that respect, advances are not only at the front of scientists’ minds but also on the minds of members of the public.

It is exactly those reasons that make astrobiology perfect for science outreach in general. It is something that draws public attention, asks questions that are very captivating such as whether we are alone in the universe, whether there was life previously on other planets in the solar system or whether it could exist somewhere else in the system even now. It is very interdisciplinary and it can be used to communicate more abstract concepts such as the science of spectroscopy that analyses the light from distant stars. Starlight that goes through the atmospheres of planets enables us to probe the chemical composition of those atmospheres.

In itself, it can seem very abstract, especially if we went into all the details, but when wrapped in the astrobiology label, it becomes more accessible and relevant. Knowing the atmospheric composition of exoplanets can help us ascertain whether they have conditions for life or even whether the activity of life has altered the composition of atmospheres such as released molecular oxygen the way photosynthesis does here on Earth.

That reminds me of a popular TV series that came out during the lockdown called Alien Worlds. Its depiction of what life could be like on a number of exoplanets annoyed some viewers I know. Personally, I didn’t have a problem with it, but in any case perhaps the most interesting thing was the flipside: life here on Earth. After all, there are places on our planet where conditions are so extreme they could arguably be described as alien and previously thought unable to support life, yet scientists have known for quite a while that is not the case. Areas that are scorching hot or at great depths in the ocean beyond the reach of light.

In terms of science outreach that [kind of documentary] can explain different effects of gravity, atmospheric pressure, and different starlight, and how they would alter life if it existed elsewhere. Here we know that conditions for life on high peaks or deep in the ocean are very varied and different in terms of how it adapted. Trying to imagine life on other planets is speculation, but if it is science-based speculation, it is also useful in outreach.

You mentioned extremely hot environments and that brings us back to the usefulness and need for pure research as well. Not only is it essential in itself, but it can bring use extremely useful applications: when the species of bacteria Thermus aquaticus was discovered at Yellowstone National Park, no one imagined that it would change the world as we know it. But today we are using its enzymes to sequence genomes much faster, and that enables us to test for the coronavirus, if we return to the topic of the pandemic. A discovery that may have been seen as very inconsequential at the beginning by the public ended up changing the world very much [Editor’s note: News of the discovery dates back to April 1969].

Science fiction meets hard science

That is of course the incredible thing about science and blue skies research, isn’t it: you never know where it may lead. If we turn to the book, how many authors are in the mix and, general speaking, how varied are the views when it comes to the question of life beyond our planet?

There are 22 stories and each story is accompanied by an essay by an EAI scientist, so in total there are 44 different authors. If we focus on the stories first, the views are very different also in terms of topics. We’ll have stories about life on Saturn’s moon Titan – an extremely interesting place – the only moon in our solar system with a substantial atmosphere that is even thicker than our own. There is lots of liquid on its surface but it’s not liquid water, but light hydrocarbons such as methane or ethane, and lots of interesting organic chemistry.

It has long been speculated that it might be a site for alien life, but of course not life as we know it, because it would have to be adapted to a different solvent. Light hydrocarbons are nonpolar as opposed to the water molecule, which is polar – has an unevenly distributed charge. So it would basically turn the chemistry of life on its head compared to what we know here on Earth. The temperatures are also extremely cold there. NASA will be sending the Dragonfly probe there in about 15 years’ time. Until then we can explore what potential life might be like there with science fiction.

We also have stories about SETI and how we are trying to listen for radio transmissions as a sign of alien civilisations and why it is not easy. There are even more exotic environments and lifeforms, stories about space colonisation gone wrong and planetary protection: trying not to contaminate other celestial objects, and also to avoid back contamination - bringing alien life back to Earth with potentially severe consequences. That doesn’t mean a new disease or parasite that would infect Earth life, which is unrealistic because an alien form would probably struggle to survive here and wouldn’t be adapted to an entirely different branch of life.

But even then it could have potentially disastrous consequences, producing metabolites which could be poisonous to Earth life, or outcompeting Earth life when drawing some biogenic element from the environment, such as sulphur or molybdenum, and that might impact whole ecosystems and the Earth’s biosphere. That’s why avoiding contamination is so important. There is a lot to explore there from the point of view of science fiction and areas to explore on how to prevent it. That is just a small snapshot of some of the things that will be in the book.

The accompanying essays are a very interesting and important aspect and I imagine a kind of anchor when it comes to science fiction and hard science.

They take the science even further and to explore it more in depth. A fiction story can only say so much about the science while focusing on the story, but the essay can go further. If we take Titan as an example again, it not only has the hydrocarbon seas and oceans and rivers, but it also very likely has a water and ammonia sea deep below its icy shell, which could also potentially host life or interact in interesting ways with the surface chemistry. It's not likely all of that would make it into the story, but the essay is there for the curious reader.

There are also stories about exoplanets with similar environments to Titan, but warm Titans or super Titans, so that is something that the essays can explore and that allows the book to be used in further outreach and education activities. We would also like to introduce some kind of accompanying game or use the text also in a non-formal educational environment.

Brand new stories from both established as well as up-and-coming authors

Are the stories that will feature in Life Beyond Us new, previously unpublished? And the big question: who are some of the authors?

All the stories are completely new, commissioned for Life Beyond Us and connected by the common theme of astrobiology. We have authors from all around the world, from Europe, Australia, Canada, the US and elsewhere, quite a broad cross-section. If the kickstarter goes well, we will also add stretch goals. All of the stories are written in English, but including translated stories from different languages are some of the stretch goals.

As far as the writers are concerned, Peter Watts is pretty famous and his novel Blindsight was also translated into Czech. It’s a brilliant novel using hard science. It is about a human encounter with an alien intelligence in a way most of us wouldn’t imagine it. Another well-known author is Gregory Benford, a veteran of science fiction who published many novels with Larry Niven, also frequently translated into Czech. Mary Robinette Kowal is famous for her Lady Astronaut series, an alternate history when an asteroid hits Earth in the 1950s and prompts people to jump-start space travel and establish colonies on the Moon and Mars, starting with 1950s technology, and the technology takes a different turn. She has just been nominated for the Hugo Award in two categories: Best Novel and Best Series. I love how the series reads almost like history novels, with very realistic technology inspired by actual spaceflight history, and at the same time creates a completely different world. Her story in the anthology will also be set in this alternate universe and it explores exoplanet detection. Stephen Baxter is also very internationally famous and there will be two Czech authors, Tomáš Petrásek – who is very active in astrobiology and science outreach besides writing SF – and Lucie Lukačovičová, who is very well known in Czech science fiction and fantasy circles.

Getting original stories from professional authors for a new anthology was the reason we went with a crowdfunding campaign, because that is one way of covering all of the associated costs, including potential translations. So we are trying to get the word out across different platforms and the campaign lasts 30 days. It is rewarding to see people getting involved. Backers can choose whether they want an e-book, a paperback or even a special limited edition with reprinted illustrations by the 19th century/early 20th century naturalist and nature illustrator Ernst Haeckel that are just fantastic in their depiction of life on Earth, and other rewards such as story critiques, a music and science show, astrobiology talks for classrooms and more. We are looking to deliver the book by September 2022.

I have to say the book looks fantastic and I am really excited about the special edition. Potential backers should have a look at the campaign. I’d like to finish along the lines of how we started: the future. You are a biologist yourself, finishing your PhD at Charles University and an established science fiction writer, so I’d like your view. Against the immense endeavour of future planetary exploration, we face massive problems at home on our own planet, from overpopulation and dwindling resources to global warming, plastics pollution, social upheaval and other dire problems. Should we be focusing on the stars when there is so much unsolved and unresolved at home?

I don’t think it is an either/or question. It takes us back to the topic of pure research already mentioned: if you imagine technology such as spaceflight, it allows us to devise many solutions even in other areas. If we go back to the Thermus aquaticus example, if that hadn’t happened, we wouldn’t be nearly as far along as we are today when it comes to real applications. We wouldn’t be able to do fast PCR tests for Covid-19, to sequence the genome as quickly and so on. To blame spaceflight for diverting resources is, I think, unfair and it is one of the smaller expenses by comparison to all the other things the EU or the US, for example, spend money on. We need space research for the pure knowledge and eventual applications it brings us, and for that we need spaceflight.

| Julie Nováková, PhD student |

| She is a scientist, educator and award-winning Czech author and editor. She published seven novels, one anthology, one story collection and over thirty short pieces in Czech. Her work in English appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, Clarkesworld and elsewhere, and has been reprinted e.g. in Rich Horton’s The Year’s Best Science Fiction & Fantasy 2019. She edited an anthology of Czech speculative fiction in translation, Dreams From Beyond, co-edited a book of European SF in Filipino translation, Haka, and created an outreach anthology of astrobiological SF, Strangest of All. Julie's newest book so far is a story collection titled The Ship Whisperer (Arbiter Press, 2020). She is a recipient of the European fandom’s Encouragement Award and multiple Czech national genre awards. She’s active in science outreach, education and nonfiction writing, co-leads the outreach group of the European Astrobiology Institute, and is a member of the XPRIZE Sci-fi Advisory Council. Her current project is editing an ambitious anthology of 22 SF stories and 22 accompanying astrobiology essays, Life Beyond Us. |