“Academics of the 20th century were celebrities. The current system, unfortunately, prefers more of the same: the same way of working and the same type of results. We should be inspired by them and encourage originality and finding one's own way, because it leads to knowledge and great ideas,” says Libuše Heczková from the Faculty of Arts of Charles University.

Thank you for the opportunity to take photos at the General Physics Teaching Cabinet of the Mathematics and Physics at Charles University.

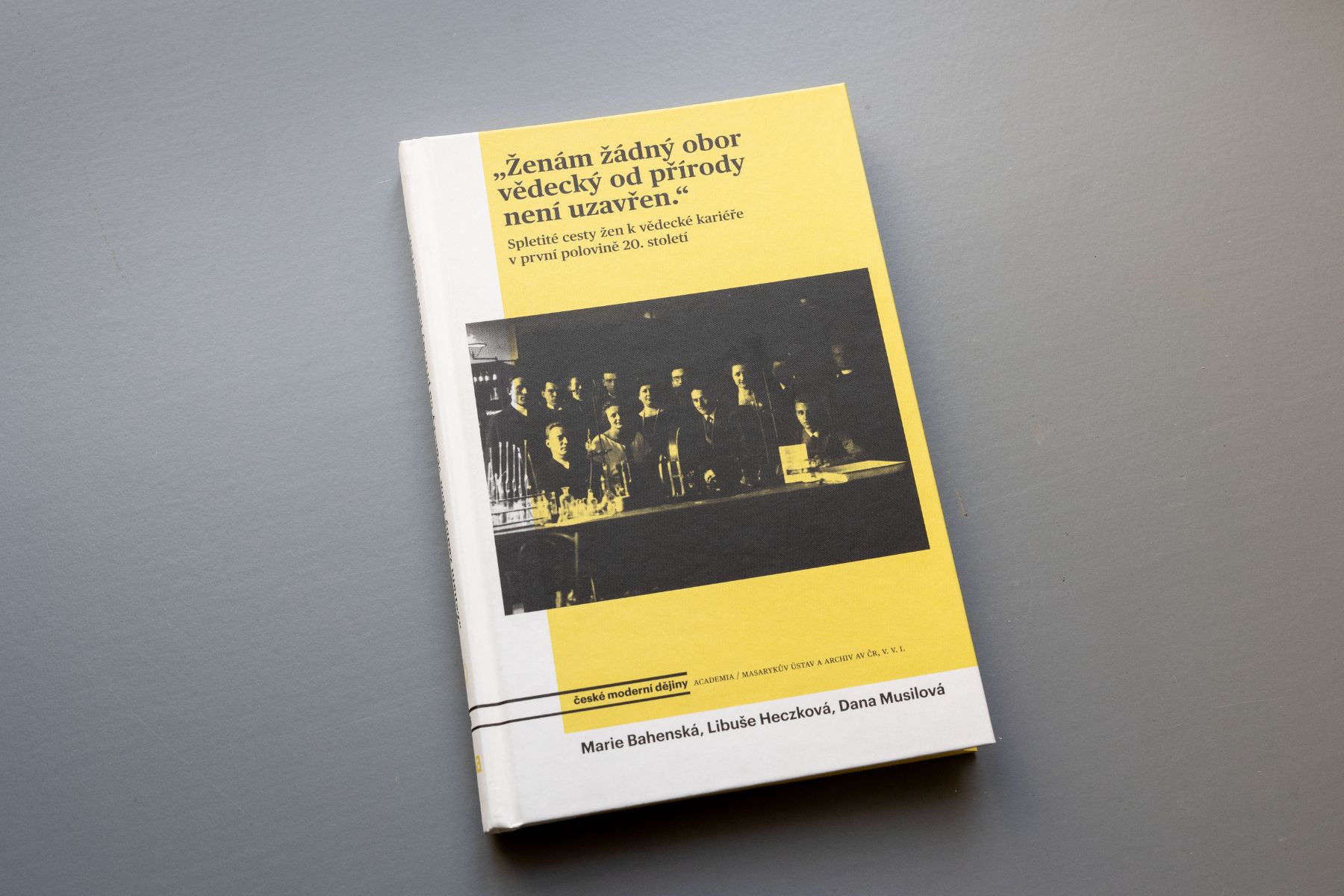

Together with your colleagues Maria Bahenska and Dana Musilová, you wrote a book called Ženám žádný obor vědecký od přírody není uzavřen (No Scientific Field is Inherently Closed to Women). What prompted you to do so?

I have been working on the historical status of women for the last 30 years. My colleagues and I had previously written a book on women's thinking and then women's work, which was a key topic for us because we had all experienced what it meant to reconcile academic careers and family. In doing so, we repeatedly came across stories of women academics that should be talked about more. It has been really exciting work, and although the book has now been published, we stress that this is only the beginning, there are still many interesting stories in the archives waiting to be processed.

What surprised you the most in the project?

That, paradoxically, we ourselves had many preconceptions. After all, a strong current of female academics in the first half of the 20th century can be found in the sciences and medicine. Perhaps this is because the natural sciences, and specially the new, interdisciplinary ones such as physical chemistry and biochemistry, were uncertain and did not provide a sufficient number of authoritative career paths. The men who worked in these fields were open not only to new topics but also to women working in the same spheres.

So, one of the most remarkable results of our work is that today's prejudices, which still somehow persist, that women are not suited to these fields, are wrong, and you can see that at the very beginning. On the contrary, in the traditional fields, especially in the humanities, it has actually been difficult for women to get a foothold.

In the book, you have charted many of the stories and fates of women scientists in the 20th century. What do they have in common?

In general, the women we write about were great personalities. They had to be very exceptional, courageous and determined to make it in their fields. And they had to be strong not only scientifically but also in their personal lives, many of them faced very difficult life vicissitudes after 1948.

At the same time, it must be stressed that they were no saints. They were women with all kinds of flaws, different types of ambitions and personal goals. We sometimes say that they were unpredictable "mavericks", in the sense that they did not conform to traditional ideas.

Can you give some specific examples?

That's always hard, every story is inspiring in its own way. But I definitely have to mention the art historian and archaeologist Růžena Vacková, who was a key figure for our Faculty of Arts. And in the field of philosophy I would like to mention Albína Dratva.

In the natural sciences, I will mention the eminent physical chemist Adéla Němejcová-Kochanovská or the later professor Julia Hamáčková, who even became the director of the newly built wastewater treatment plant in Prague.

Very remarkable is the story of pharmacist, forensic expert and one of the founders of forensic chemistry, Emilie Laubová-Kinská. It must have been difficult to get along with her, because she was a very strong personality. She took part in the investigation into the death of Foreign Minister Jan Masaryk and, as a forensic chemist, also in the investigation of the parish priest Josef Toufar, so you can guess how she ended up... But she also showed her strength and determination during her stay in the Pardubice prison, where she took part in a hunger strike despite her serious illness. Unfortunately, she died shortly after her release from prison.

Also important for me is the German Jewish intellectual and outstanding philologist Käthe Spiegel, who also did a fellowship in the United States. Her father was at one time rector of Charles University, yet because of her racial origin she was not allowed to become an associate professor and eventually ended up in a concentration camp.

For some women, however, Jewish ancestry was not so much of an obstacle, perhaps they followed their research obsessively. One of them was definitely Julia Moscheles, the founder of modern Czech geography, especially social geography, who, probably thanks to the intervention of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk, after not being able to work at the German University, got into Charles University and then, under very strange circumstances, into the Women's College in Melbourne, while at the same time working for the Dutch secret service during the war. On her return she had a hard time, although she was a top scientist who published in five world languages, living in a studio apartment in the Faculty of Science at Albertov in Prague.

A controversial figure was one of the founders of the Institute of Criminology, Associate Professor Jarmila Veselá, a lawyer who worked in criminal law and was one of the few to transfer to a German university during World War II. Her devotion to her field probably prompted a level of 'blindness' to what criminal law was all about.

As I read the book, I had the sense that contemporary scholars are still grappling with similar obstacles even today. Do you ever feel that we haven't moved on much since the first half of the 20th century?

The status of women in science is evolving, but it's true that for all the social emancipation and feminism, there hasn't been much reflection on what it really means to be a woman in academia. A woman academic is not just a part of the work force. Again, it comes back to the fact that she must be a someone who has something to pass on to her male and female students.

However, there are also opinions that we have moved too far and that we are feminising and therefore degrading the sciences in particular. Of course, the dual careers of married couples or even their scientific collaborations remain complex. A prime positive example is that of Gerty (Radnitz) Cori and Carl Ferdinand Cori, who won the Nobel Prize together in 1947, or the much less well-known couple Renate Junowitz-Kocholaty and Walter Kocholaty, biochemists whose careers are mainly linked to penicillin research at the University of Pennsylvania, where they went before the Second World War.

Did you discover anything in your work that we can take inspiration from today?

It's very hard to apply something from structures that were different. But we have one thing in common, and that is difficulties faced by PhD students. In the First Republic and today, there was a lot of talk about it, but the situation is still bad, we are closing the door on talented people.

But I will mention one difference that bothers me somewhat, and that is that the academics of the 20th century were personalities. Unfortunately, the current system prefers sameness, the same way of working and the same type of results. We, on the other hand, should encourage originality and the search for one's own way, because only that leads to knowledge and great ideas.

What are you working on now?

I am part of several large and long-term projects. But my own research, which I find very interesting and fulfilling at the moment, is about reflecting on women's thinking. What does it actually mean when a 19th century woman entered an intellectual milieu and brought with her themes like motherhood, caring, and relating to the other. I would therefore like to return to the thinking of figures such as the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas, who was intensely concerned with the question of the 'other'; the political philosopher Hannah Arendt is also important to me; and I want to focus on contemporary scholars who are working on the problems of contemporary democracy, such as Bonnie Honig. I'm interested in how to describe women's thinking and how to deal with it as an intellectual challenge, not to marginalize or exaggerate these concepts, but to put them at the centre of who we are and what we want.

| Associate Professor Libuše Heczková |

|

Libuše Heczková is the Director of the Institute of Czech Literature and Comparative Studies at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University. Her main areas of interest include 20th century literature and cultural history, gender studies, literary theory and didactics of literature. |