As a young man, he was fascinated by the starry sky and regularly visited an observatory, which led him from Brno to the University of Prague’s Faculty of Mathematics and Physics. This was followed by time spent in the US, including Princeton and receiving a NASA space agency fellowship, after which physicist Ondřej Pejcha returned to the Czech Republic. In 2018, he earned a prestigious European Research Council (ERC) grant at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics. That was a Starting Grant studying binary star interactions and just recently he clinched a follow up: a Consolidator Grant for more experienced researchers. The grant is worth €2.3 million for five years of research by his team.

Then there were two: Ondřej Pejcha clinched a second ERC grant - a rare, well-deserved success to power his research over the next five years.

In December 2024, Ondřej Pejcha has secured his second ERC grant. The likable astrophysicist and now associate professor is also one of the main “faces” of the successful CU Primus programme for young group leaders at Charles University; securing an ERC grant for the second time, is however, a rare success. “This time, I’ll focus on a project titled Dynamics of fluids in binary systems composed of stars and black holes. The goal is to perform previously unachievable magnetohydrodynamic simulations of binary systems consisting of stars, planets, neutron stars, and black holes,” Pejcha told Forum magazine, adding that advances in understanding will enable better interpretation of other observations from both ground-based and space observatories.

“Of course, I’m pleased that I succeeded; actually, I applied three times. Before applying for this grant, I consulted with Matyáš Fendrych at a Czexpats in Science event on how he approached his second application,” Pejcha says about the plant biologist, who also received a Starting Grant in 2018 and a Consolidator Grant in 2023 for the Faculty of Science at Charles University and the Czech Academy of Sciences.

If I’m not mistaken, for the second ERC grant, you couldn’t just "develop the same topic," but it had to be a new idea, a new concept. Can you compare both of your grants: the Starting grant and now the Consolidator Grant? When we spoke five years ago, you focused on binary stars. Are you building on what you discovered over the past years?

The ERC Starting grant was aimed at understanding just one specific phase in the development of binary stars, called common envelope evolution—it’s the most mysterious phase of binary star evolution, yet very dynamic. The stars move very close to each other, and a lot happens. However, there are still many unresolved issues even when the distance between the stars doesn’t change much. Interesting phenomena in such cases include mixing of material inside the stars, accretion disks around binary stars, and mass transfer between the two stars. We've known about these processes for decades, but we still don’t have precise knowledge of what happens and how.

So, you came across a situation where, in addition to the main problem, there are many other questions?

Of course, I knew that in advance - these are basic things in binary star astronomy. But let’s say I became more aware of the theoretical uncertainties connected with everything, because studying something for decades doesn’t mean we know some parameters in the theory better than we did thirty years ago.

Did the ERC review panel ask about your findings from the first grant?

During the interview, no one asked about that, but the results from the first ERC grant certainly played an important role in the application, as part of the “track record.” So, I think that was fine.

How do you evaluate the results of your Starting Grant? Are you satisfied with the outcomes?

Probably, in the end, yes. The grant runs until the end of June 2025, by which time we have to complete the final task, and the years of developing the method will culminate in its application to the problem we were interested in – the common envelope evolution. In some other aspects, what I originally envisioned didn’t exactly materialise. However, we completed a different set of simulations focused on another phase of common envelope evolution, one that hadn’t been specifically addressed before. So, I can say the spirit of my proposal was fulfilled, although the method ended up being somewhat different.

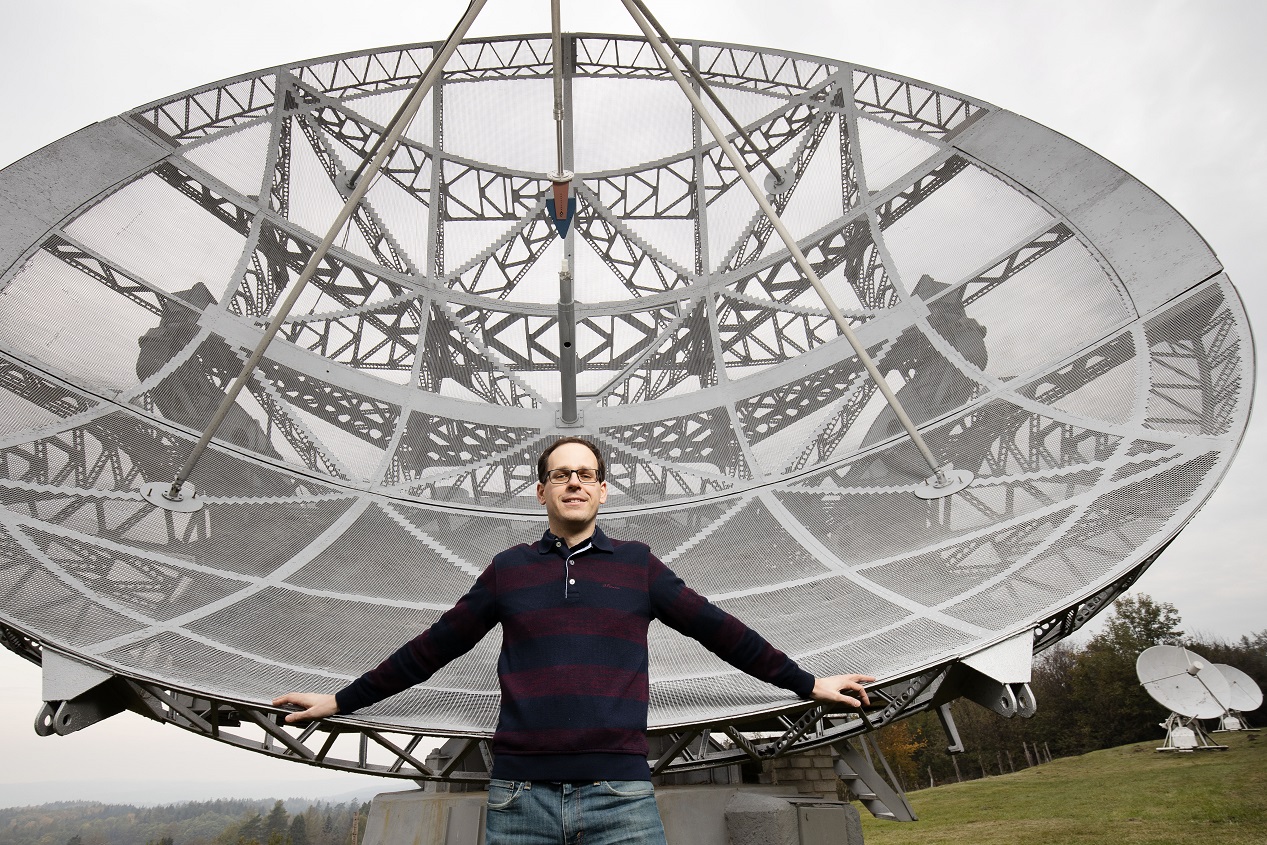

In 2021, astrophysicist Ondřej Pejcha was photographed by Michal Novotný in Ondřejov.

In 2021, astrophysicist Ondřej Pejcha was photographed by Michal Novotný in Ondřejov.

Who was part of the team during those five years?

The backbone of the team was made up of two postdocs. The first was Diego Calderón from Chile, who spent just over three years in Prague, and based on his work at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, he was offered a postdoc position in Hamburg with Professor Stephan Rosswog’s ERC Advanced grant and also a Humboldt Fellowship at the Max Planck Institute in Garching, Germany, where he is now. The second was Damien Gagnier, originally from France, who was also with us for over three years. Last September, he moved to Heidelberg to join Professor Friedrich Röpke’s group, who also holds an ERC Advanced grant and studies the same phase of binary star evolution as we do. Damien also had several postdoc offers to choose from.

And are they continuing with the work they learned from you, or are they working on entirely different topics?

Damien Gagnier delved deeply into the topic and became an expert on binary stars. In fact, he managed to combine his knowledge of solitary stars from his PhD with what he learned with us. I think his papers will be important. Diego Calderón has broader interests, so he’s also exploring topics like tidal disruption of stars by black holes and more.

So we will likely hear from them again.

I hope so! With the PhD students in our group, it was more complicated because they were transitioning from different grants—initially, we had the university Primus grant, then a Ministry of Education grant, and now I also have the GAČR grant. But I’d like to mention Camille Landri from France, who is the first PhD student to graduate with me. Since September, she’s continued at the Catholic University in Leuven, Belgium. The second PhD student who graduated is Milan Pešta, who, thanks to the "postdoc outgoing fellowship" from GAČR, is moving to Ohio State University in the USA.

You were there too, right?

Yes. I did my PhD there, but in this case, it’s really just a coincidence, because Milan is going to work on machine learning with Professor Yuan-Sen Ting, who recently moved there from Australia.

You returned to the Czech Republic and habilitated. You also teach here. What courses do you lead?

I teach a mandatory course for the master's programme Fundamentals of Plasma Theory, which is also relevant to my scientific work since I study plasma (the course is partially co-taught with Professor Radomír Pánek, who will become the future head of the Czech Academy of Sciences and is an expert in thermonuclear fusion in European organizations). In the spring semester, I’ll be co-teaching Principles of Physics IV for the new BSc Science programme run jointly by the Faculty of Science and the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics. Besides that, I also lead a selective course Astrophysics of Gravitational Wave Sources and a seminar called "Science Coffee."

Do you enjoy teaching?

Yes, I really like being in the university environment, especially because of the contact with students; it’s important to me, and it helps me find a balance between teaching and research.

At 40, people are already asking when you'll become a professor?

Yes, they do (smiles). I’m thinking about it, but I haven’t taken any concrete steps yet.

Is astrophysics at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics a standalone field, or a specialisation within physics?

Students have astronomy as a separate field in the master’s programme. Astrophysics, however, also overlaps with theoretical physics.

If someone reads our interview in Forum and says, “I want to be like Ondřej Pejcha, I want to study stars and I really enjoy it,” what can they do?

They should come to us at. In the bachelor’s programme, they study general physics, and then they specialise in a specific field during the follow-up master’s. Or they can come directly to me.

Even as a first-year student?

Yes! Just last autumn, a student came to me at the beginning of their second year and said exactly what you mentioned—that they’re interested in astronomy and want to pursue it. We agreed on it. They’re really smart.

| ERC doubles |

| Securing an ERC grant twice is an extraordinary achievement, demonstrating both continuity in global research and the diversity of scientific ideas, as the new proposal cannot just "develop" the previous one; it has to be innovative again. In the Czech Republic, Professor Tomáš Jungwirth has received two ERC grants for spintronics (even in the most advanced Advanced category, in 2010 and 2023), economist Filip Matějka from the CERGE-EI institute (Starting 2015, Consolidator 2020), plant biologist Matyáš Fendrych at the Faculty of Science at Charles University/Czech Academy of Sciences (Starting 2018, Consolidator 2023), and mathematician Libor Barto from the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics (Consolidator 2017, Advanced 2023). Source: Forum, ERC, archive |

Let’s talk about the current ERC Consolidator Grant. When you compare the first and the more advanced one, was it more difficult? Did the commission ask you tougher questions?

Well, I’ve actually been to three ERC interviews – the first one wasn’t successful – but each of the three was completely different. This time, I didn’t even know what to prepare for... I had practice interviews, like the ones organised by Professor Zdeněk Strakoš at the Technology Centre in Prague, and a trial presentation in front of several foreign colleagues. Associate Professor Václav Kučera from the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics at Charles University helped me with the preparation, with whom I consulted the numerical method and who is also a member of my team.

When comparing your two successful interviews, in 2018 and 2024, how did they differ?

At the first ERC Starting Grant interview, there were mostly questions about scientific aspects, while the ERC Consolidator interview included a lot of technical questions, such as why this particular method, why not others, and why it didn’t work for people before me. I was surprised that they didn’t ask anything about the budget, even though I had presented a request for an increase in the grant limit beyond two million euros due to access to large infrastructure. They asked more about how I would look for and hire postdocs, and finally, there was a question about what scientific achievement I would show off to my elementary school teacher in ten years.

What did you tell them?

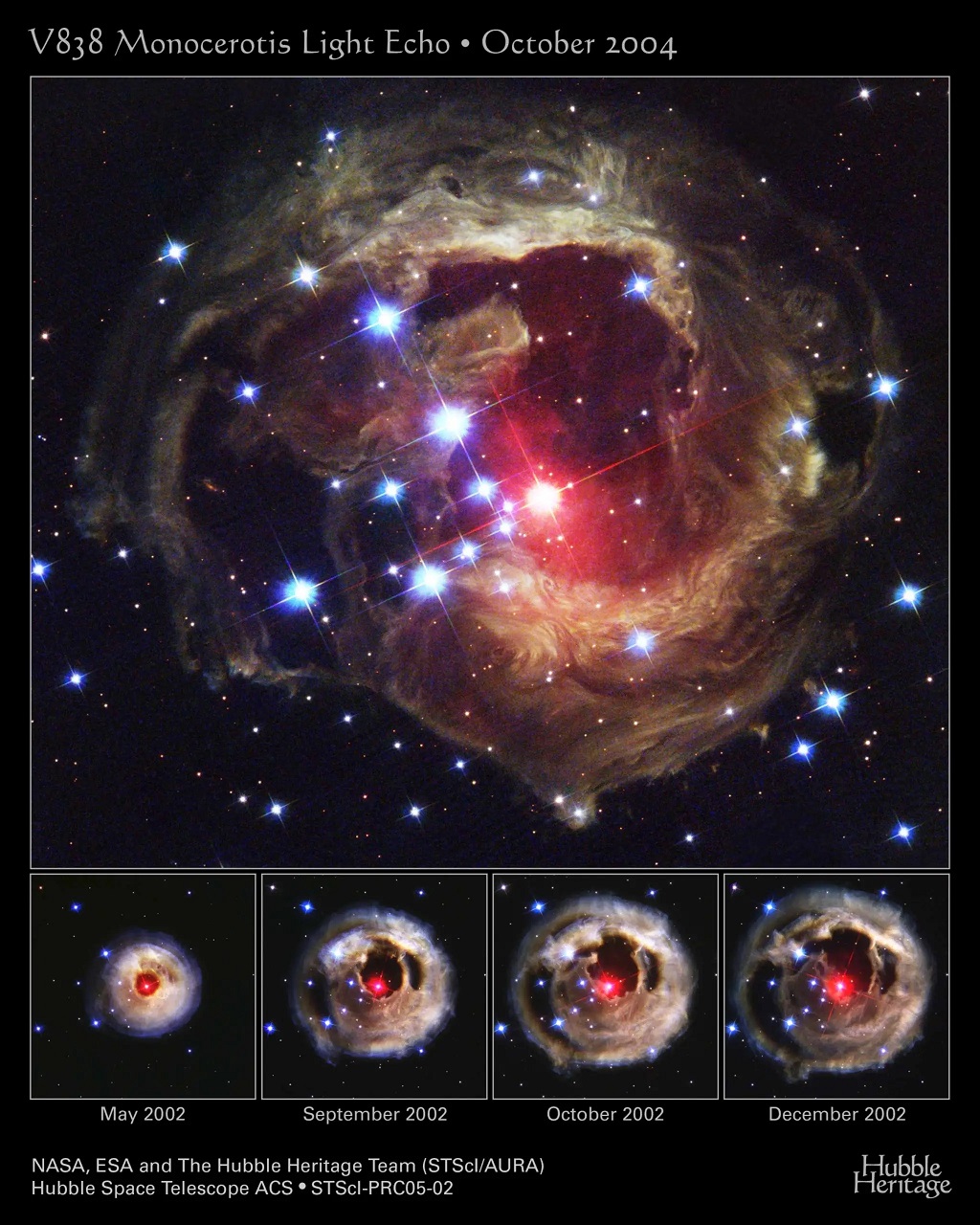

That I hope to discover something truly new (the image on the right is probably the most famous merger of binary stars V838 Monocerotis captured by the Hubble Space Telescope).

German institutions and names appear in our conversation. Could it be said that the Germans play a leading role in your field?

Germany is certainly historically strong in stellar astrophysics, with two main centres: Garching near Munich, and Heidelberg, where there are also Max Planck Institutes focusing on stellar astrophysics. But it’s also the Netherlands: Radboud, Amsterdam... And of course, England – Cambridge, Oxford.

I remember that years ago you had a lot of praise for Ohio in the US as well.

From the perspective of the doctoral program in astronomy, Ohio State University ranked seventh in the nationwide U.S. ranking. However, for example, they don’t do much theoretical work on binary stars, and I personally started working more on this area only during my postdoc at Princeton.

How is the situation in the Czech Republic?

There are many people who observe binary stars. But there is also a long tradition in theory, which goes back to Professor Miroslav Plavec, who ultimately ended up at the University of California Los Angeles, or to Zdeněk Kopal, who spent most of his career in Manchester. These were people who had a global impact on binary star astrophysics in their time. Another such person was the recently deceased Luboš Kohoutek, who worked in Hamburg for a long time, where he studied planetary nebulae. Many planetary nebulae today are believed to be the result of binary star evolution in a common envelope.

Let’s return to the latest developments. You mentioned that you need to pay extra for access to some large infrastructure – do you need it for a telescope, or is it about computational power?

I am a theoretician, so I need a computational cluster. In the Czech Republic, we have the national IT4Innovations infrastructure (IT4I, a supercomputing centre in Ostrava worth two billion CZK, which was created from the OP VaVpI – editor’s note), which we generously used during the ERC Starting grant and thanks to which we had a competitive advantage over colleagues abroad because we were able to do larger computations than they could. However, this infrastructure is shared, and sometimes it takes a while to start tasks. For code development and debugging, we need immediate execution, which is best achieved through exclusive access to a small local cluster. From the grant, we will purchase several dedicated computational nodes directly in the cluster here at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics.

How much time do you need to compute your stellar tasks?

For production tasks, like the ones Damien Gagnier had in 3D, he needed about ten million computational hours per year on IT4Innovations.

Ten million computational hours... How much actual time and processors did that take?

Professional codes are capable of running on several hundred nodes, meaning thousands of processors, and computations take several weeks.

The Nobel Prize in 2017 confirmatinggravitational waves was a huge motivation and boost for our entire field, says astrophysicist Ondřej Pejcha.

Part of your five-year budget of 2.3 million euros (58 million CZK) – besides salaries for all the researchers and similar expenses – will go to this. What is the main scientific theme and focus of your new ERC?

The theme of the new grant is best compared with the first grant when we were interested in a specific phase of binary star evolution. Now, however, we are more interested in developing a computational method to study the structure of binary stars, which has potentially much broader applications for many problems across astrophysics. Our focus will be on both binary stars made of “ordinary” stars similar to our Sun, as well as stars orbiting compact objects (white dwarf, neutron star, black hole), but also on the dynamics of gas around binary supermassive black holes at the centres of galaxies.

It’s not entirely possible to say that we will answer one specific question, but each type of binary star has its open questions, and we will contribute to their solution. The specific choice of topics depends on the interests of future team members, but personally, I am particularly interested in material mixing inside stars, which can lead to chemically homogeneous star evolution, which is important for the formation of gravitational wave sources. Another area that interests me is circumbinary disks, which are rotating gas structures around binary stars, where these three bodies interact in complex ways. The third area involves explosions, such as classical novae, where one of the stars in a binary system undergoes an explosion that affects the binary companion.

You mentioned the 2017 Nobel Prize for gravitational waves. Are you touching on this major phenomenon?

It’s certainly a huge motivation and boost for our entire field. Previously unanswered problems suddenly have much higher urgency due to the detection of gravitational waves; we now have new objects, interests, and methods for studying this complex area.

How many people will be on your team this time?

I plan to have two postdocs plus three PhD students. This has proven to be the ideal size for a scientific team, allowing me to still interact with everyone, go deeper into the work, and at the same time, the team is large enough that members can interact among themselves.

When will your project start?

The new ERC Consolidator grant can begin only after the previous one ends, so it will be from 1 July 2025. I will be selecting team members in the coming months, but they will realistically start in the fall, according to the academic year cycle, i.e., at the start pf the semester. I am looking for team members from all over the world, and the application deadline is the end of this January.

| Associate Professor Ondřej Pejcha |

| Ondřej Pejcha received an ERC Starting Grant in 2018 and now the higher category ERC Consolidator Grant in late 2024. He studied theoretical physics at the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics at Charles University (2008), then continued his astronomy studies at Ohio State University, where he earned his PhD in 2013. He later worked as a postdoc at Princeton University in the USA, where he also received a prestigious NASA fellowship. In September 2017, he returned to the Faculty of Mathematics and Physics at Charles University in Prague through the university's CU Primus program for new groups of promising researchers. He also habilitated here. He is the author of about 50 studies with approximately 2,500 citations; with his wife Eva – also a scientist – they are raising two daughters. |