He first glimpsed the ancient world through the viewfinder as a teenager on a family holiday in Tunisia and for David Rafael Moulis it was a turning point. His camera eventually led him to Israel, as a member of a team from the Protestant Theological Faculty at Charles University. Moulis fell in love with archaeology and this year published his first monograph: Religious Cult in Ancient Israel through the Archaeological Perspective.

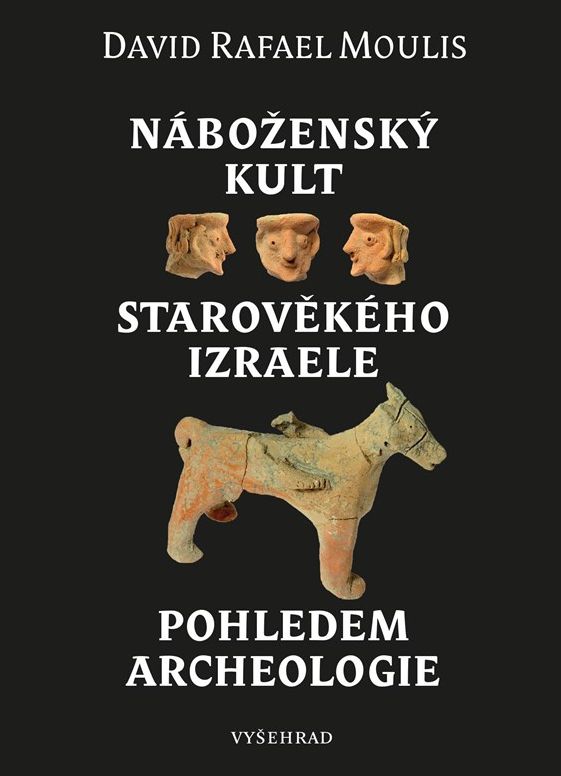

Ten years ago, the discovery of a settlement and an almost three thousand year old temple at Tel Moza during the construction of a highway between Jerusalem and Tel Aviv, caused a sensation. It is easy to see why. The temple’s parameters in many ways echoed the description of the legendary First Temple thought to have stood on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem in Biblical times. Evidence of which has never been found. When scientists began to uncover the remains of the site six kilometres from Jerusalem so strikingly resembling the mythical Temple of Solomon, it naturally raised many questions. Some were answered quickly: no, there was no way it was the legendary First Temple. That was refuted almost immediately by scientists, but many other questions remained. David Rafael Moulis tried to answer many of them in his 240-page book published by Vyšehrad.

Iron Age II

The focus of Moulis's interest is the Kingdom of Judah and the religious cult practiced by its inhabitants during the Iron Age II period (from approximately 1000 to 586 BC). In his book, the author takes the reader to particular archaeological sites, most notably an Israelite temple found at the mound at Tel Arad discovered in the 1960s in the Negev Desert, as well as to Tel Moza. Indeed, Tel Arad was the only such sanctuary from the time of the Kingdom of Judah until the discovery of Moza. Moulis also discusses individual altars, incense burners, cult pottery, and various Iron Age figurines that were discovered at other archaeological sites in present-day Israel.

He does not have a clear answer to the question of which cult people actually followed in the Kingdom of Judah during centuries, as there was almost certainly an overlap of old practices and new, official and otherwise. “We can't say for certain who was worshipped in every cultic place. There was a main cult dominant in Jerusalem and another entirely in households where older practices probably persisted. The state cult provided for the running of the state as such, but the people had quite different needs. They saw to these themselves - at local shrines or in domestic rituals. I believe that people not only worshipped the official deity, Yahweh, but that for a time the old Canaanite traditions lived on. People at the time still addressed deities they had worshipped before,” he notes.

Excavation

Moulis describes the archaeological work he does as part of a team from CU's Protestant Theological Faculty led by Professor Filip Čapek as a kind of “mosaic” that scientists have tried to piece together. The drawback? No one knows with certainty how broad the mosaic is or how detailed… To fit the pieces together correctly, to build a better approximation or model, experts combine all available sources, from biblical texts to extra-biblical records and archaeological finds. “Reading my work, it might appear at a glance that we can now close the book on what the Kingdom of Judah cult was like. But we still know very little about it. We’re working only with what has been found. We don’t know what was lost, what did not survive, what may have been destroyed deliberately or removed. We don’t have a preserved moment of what life was really like back then, something that archaeologists were able to capture at Pompeii. In making interpretations, we work with our knowledge – we apply our perception of our world to Antiquity – but there is always a little room for error. We can only wait for the next find that will bring us closer to what life then was really like. The fragments we have are tiny, yet the mosaic was enormous,” Moulis explains.

The researcher and photographer points out that the approach of the first biblical archaeologists who dug “with Bible in hand”, so to speak, has now been overcome. Trying to fit finds along with what was written in the Old Testament did not always work and distorted their meaning. “Today, we approach archaeology independently of the biblical text, because we know that it took quite a long time before those texts were completed in their final form. Biblical texts were intended as a lesson, not as a direct historical account. However, it is of course interesting for us to look into the Bible to see what it says about different localities. We can thus get a better picture of, for example, what the relationships between the Judeans and the Philistines were,” the archaeologist continues.

Therefore, what can we read in the “book of books”? It is interesting that Tel Moza is mentioned only once in the Bible. The temple, which must have been truly significant in its heyday, is never mentioned: that is a mystery that archaeologists – working together with theologians and other specialists are trying to unravel.

A decade of commitment

David Rafael Moulis has been going on expeditions to Israel for over a decade but his path was not always clear-cut. His profession as an archaeologist and official photographer at Tel Moza was not always obvious although today the 38-year-old Plzeň native is glad with how things turned out. As a student, he had also been attracted by the field of cybernetics and could have easily opted for the former instead of cultural anthropology and archaeology. However, he says, the allure of the Middle East proved stronger. Perhaps that is why he earlier began to guide tourists around the synagogue in Plzeň and to learn Hebrew. When he was thinking about continuing studies at university, he applied to several faculties at the University of West Bohemia including the Faculty of Applied Sciences, where he was accepted. He had also applied at the Faculty of Arts, with the aim of majoring in Middle Eastern studies. “I thought I might regret it later if I didn’t at least try. When I was accepted, I was surprised… but I didn’t hesitate,” he says.

Moulis was completely absorbed by his studies that included contemporary Middle Eastern history, literature and art. He increasingly felt drawn to the roots of early civilisation – aspects that had appealed to him once upon a time in Tunisia but also later, during his studies, on trips to Israel, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon and the great museums of Europe. “When I arrived at the Louvre and went to the exhibit on Mesopotamia, where I saw in person the artefacts I knew from lectures, I knew this was what I was looking for. I didn’t just want to know things from books, I wanted hands-on experience,” Moulis recalls.

A Czech in Jerusalem

He had begun to focus on antiquity and was looking for an opportunity to pursue archaeology in Israel, which led Moulis to the Protestant Theological Faculty at Charles University, where he continued his doctoral studies under the guidance of Professor Filip Čapek. The latter had long included students in fieldwork at sites in Israel, where they were making a difference alongside teams from other universities from around the world. Moulis then spent a year in Jerusalem at Hebrew University, which he describes as a life experience that he still draws on today. “It changed the way I look at the world and the ordinary difficulties in our lives, which we often give far more importance than they deserve. Here in Czechia we complain too often. Sometimes I feel like we’re afraid to say we’re doing well. When you live in an area where there are problems, and people are surrounded by conflict, you see things differently. It interferes or affects their lives at times, yet they don’t stress about it, but rather try to be positive and move on. It’s inspiring and Israel is an amazingly diverse country,” he says.

David Moulis wanted in expeerience in the field. He foiund ample opportunitz at Tel Moya under the guidance of Professor Filip Čapek..

When in Israel, Moulis captured that extraordinary cultural depth in his photographs. “I was attracted to Israel because there is an incredible variety of subjects and situations that can be photographed well: religious celebrations, concerts, there are always performances in the streets and people of different cultures in traditional costume everywhere. I found it incredibly engaging.”

During the year he spent in Jerusalem, Moulis helped once a week to excavate at a site in the City of David. “Part of the site is an archaeological park that is open to the public. It’s interesting when you dig in the beating heart of the city. You have buses driving by, crowds of tourists walking here and there. But when you work there, you get locked into a bubble, concentrating on what you’re digging.” He would notice his broader surroundings again only when it was time to go home for the day. Looking around, he would spot the Temple Mount, the Mount of Olives… “It’s fascinating that you’re uncovering a city that has existed for millennia. You just go deeper and deeper into history,” he says.

In free moments, Moulis hit the streets with his camera, wasting not a minute. Over the years, he captured many scenes in Jerusalem, both periods of intense tourism but also Covid lulls. “I enjoy photographing places where cultures meet. The Church of the Holy Sepulchre is a great place to shoot, where the sun’s rays hit at different angles at different times of the day and people from all corners of the world take turns coming in. It’s quite a sight. These places were far emptier during the pandemic.” the archaeologist recalls.

Working with a pickaxe in hand

Although the archaeologist returned to Prague for good, he still travels to Israel with the Protestant Theological Faculty on a regular basis. He still travels with colleagues to Tel Moza, where he became the official photographer for the project last year. This expanded his tasks, balancing between taking photos and digging. “Every morning there I have time to photograph the previous day’s finds: once I finish taking photos I grab a pick and wheelbarrow and begin digging like everyone else. If there is something during the day that needs to be photographed right away, my colleagues call me over, I drop my tools, dust myself off, and grab my camera. And then, in a little while, pick up the pickaxe again,” he laughs.

He documents more than artefacts but something equally valuable: the comradery and commitment of all those involved in the dig. “An important part of the job is showing that we enjoy what we do. When someone brings me a find they want to show and want to photograph, and are grinning from ear to ear, it’s such an authentic, genuine thing… That’s what excavations are all about: it is about more than digging in a hole in the sweltering heat. Expeditions bring together people from all over the world who are passionate about what they do. I love photographing them,” David Moulis explains.

| David Rafael Moulis, Ph. D. |

| David Rafael Moulis completed Middle Eastern Studies and Cultural Anthropology of the Ancient East at the University of West Bohemia in Plzeň, and his Ph. D. at the Protestant Theological Faculty at Charles University, where he works at the Department of the Old Testament. He specialises in biblical archaeology – with a focus on the cult in the Kingdom of Judah. Since 2011, he has regularly participated in fieldwork in Israel, not only at the sites of Khirbet Qeiyafa, Jerusalem, Tel Azekah and Tel Moza. He is an avid photographer and his work has been shown at exhibitions in Prague, Plzeň and other parts of the Czech Republic. |