Associate Professor Jan Sýkora from the Institute of Asian Studies at the Faculty of Arts at Charles University has been to Japan on countless occasions. The most influential stay was at Saga University on the island of Kyushu, where he studied between 1991 and 1994. What was it like? “My supervisor, Professor Susumu Nagano – a leading expert on the economic history of the Tokugawa period – gave me a proper lesson at our first meeting. He called me in to ask what I wanted to do professionally under his tutelage. I began outlining my plans with the utmost confidence. He listened for a while, said nothing, then reached behind, threw a stack of archive material in front of him on the table and said ‘Read!’ in a curt voice. I shuddered and began to explain that I had never encountered anything like this before… When I faltered, he pointed to the door and just said ‘Out!’” Sýkora explains. That was the moment 30 years ago when he began to immerse himself fully in a different mentality and in the Japanese culture of “suggestion”.

The Japanese version of Ad Fontes

The sensei’s decisiveness struck a chord: “I stumbled out of the study as white as a sheet and was ready to start packing my bags… The next day, I met Professor Nagano in the hallway. He was grinning from ear to ear, and said ‘So that was the first lesson. If you want to do history, whether general, economic or intellectual, you have to be able to work with primary sources. If you show up at an archive and you can’t read basic documents, you’ll never bring anything original to your research – you’ll just be copying the work of others.’ Then he suggested once a week spending the whole morning with me and teaching me the basics of diplomatics and working with documents of official provenance. And that’s how we met week after week for three years,” Sýkora says.

In 1994, he returned from Saga to Prague, to the newly independent Czech Republic. In the autumn, he began teaching Japanese palaeography and diplomatics as a separate subject, and he still teaches it at Charles University today. “At that time, almost no one in Europe was devoted to Japanese diplomatics (komonjogaku) as an auxiliary historical science, so I began giving lectures to Ph. D. students and historians at many universities: for example, in Heidelberg, Zurich, Bochum, Vilnius and Krakow.” The formative experience of Saga not only led him to an interest in Japanese primary sources, but also instilled in him the necessity of mastering the language fully – a requirement he insists on in his own students of Japanese studies. “You really can’t do anything without perfect Japanese, no original work can come into being,” the associate professor says. Over his career, he has now taught several generations of young Japanologists, following in the footsteps of distinguished predecessors Věna Hrdličková, Vlasta Wikelhöferová and Zdenka Švarcová, who, like Sýkora, also received what is one of Japan’s highest honours: the Order of the Rising Sun.

What was your reaction when you found out you were going to receive the honour?

It’s a fairly drawn-out process: first the Japanese notify you that you have been nominated. And the first question is whether or not you’ll accept it. When I was approached by a former student who now works at the Japanese Embassy in Prague, I at first thought she was joking. Even if it were true, I felt I couldn’t accept it. Indeed, I was determined not to accept the honour because I questioned why I should be eligible. Then I realised that it was an award meant not only for me personally, but also for my teachers, my colleagues and the university where I work and in the end I decided to accept the order with humility.

Do you receive a certificate signed by the emperor along with the order?

Yes, the order includes a certificate bearing the imperial seal (tennó gyôji). The honour is conferred by the Emperor, but the administration is carried out by a special office headed by the country’s prime minister. Therefore, the certificate also bears the signature and seal of the prime minister. The actual presentation is overseen by the Japanese ambassador in the country in question. There is therefore a lag in time between the announcement and the official bestowing of the order, which in my case extended to almost two years. It was impossible to meet certain protocolar requirements during the Covid pandemic. Of course, immediately after hearing back in 2020 that I had been given the order, I received personal congratulations from the Japanese foreign minister and other officials.

On one of your many trips to Japan, you took part in an official visit and met the Emperor, did you not?

I did. It was in 2007 with President Václav Klaus. Part of the state visit to Japan included a meeting and lunch with the emperor, the empress and the crown prince – that is, today’s Emperor Naruhito. There, I had the honour of acting as protocol interpreter.

How stressful was it?

I have to admit I don’t find interpreting stressful. At least, not until the actual interpreting begins! But I digress: when I went to Japan for the first time in 1986, thanks to the Japan Foundation, you know, the first time I had ever been ‘to the West’ but ironically it was to the East – I felt very small. Professor Švarcová, who taught me at a well-known language school on Národní třída in Prague, told me a memorable phrase: “Just wait, when you find yourself in need, you will remember things you didn’t even know you knew!” If you prepare thoroughly, there are things that are hidden deep in your mind that will pop into your head when you need them in real life.

Was the audience with Emperor Akihito a “once-in-a-lifetime” experience?

You don’t realise it at the time. When you’re interpreting here in the Czech Republic, even at the highest level, you’re only focused on your work for a limited amount of time. But when you are abroad you’re basically an interpreter 24 hours a day. So it’s a kind of permanent tension. It’s only when it’s all over and you get back home that you realise where you’ve been.

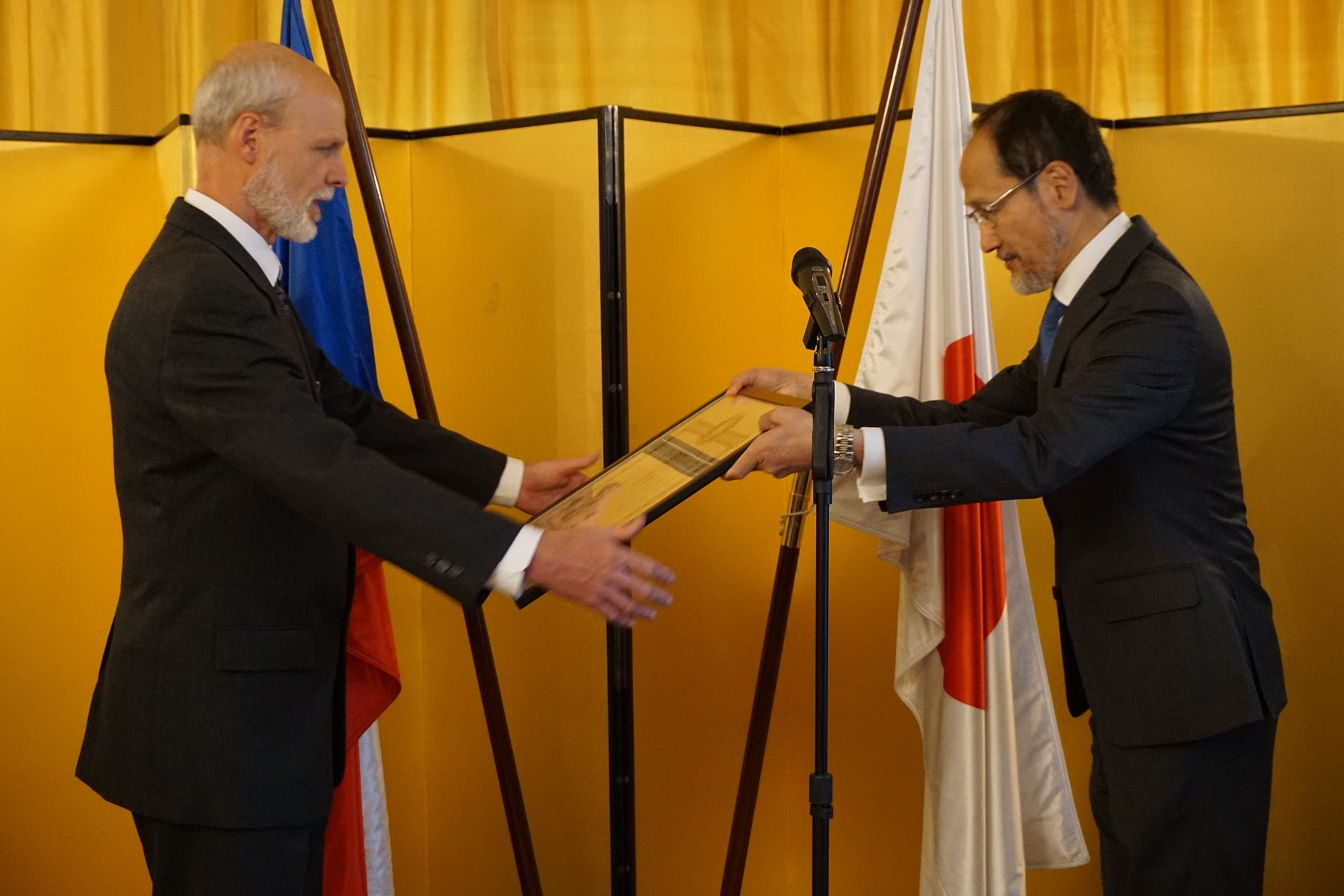

Associate Professor Jan Sýkora received the order from the Japanese ambassador to Prague Hideo Suzuki on 27 May 2022.

There must be a lot of customs and rules to follow at such a meeting. You weren’t afraid of a faux pas?

As far as interpreting for the emperor went, it was not my first experience: I had been approached by the Imperial Household Agency (Kunaichó) back in 2002. Back then, a few days before devastating floods hit Czechia, the imperial couple visited Prague at the official invitation of President Václav Havel, and the office in question asked me to help translate press releases and other documents. The first thing they gave me at the time was a booklet of about 30 pages of Imperial Japanese, because Japanese is a socially oriented language that distinguishes several levels of politeness – and one of those relates directly to the emperor.

How did you – as a kid from Jihlava in the Bohemian-Moravian Highlands – get interested in Japan in the first place?

I was studying at a high school focusing on economics, but truth be told – I didn’t really expect to go to university. When I was about 17, I happened to get my hands on a book called The Youth who was Late by Kenzaburō Ōe who went on to win the Nobel Prize for literature. It is the story of a boy who grows up during WWII and is determined to defend his country to the last breath. And that boy’s world completely collapses with the surrender in 1945; he wants to sacrifice himself for Japan, but is “betrayed”. And that sense of social betrayal marks him for life. The second half of the story takes place in the 1960s, during his college years; he’s an adult, but that sense of failure still lingers in him – he feels uprooted and unable to make social or personal, intimate connections… This book absolutely turned my world upside down! It was a revelation and made me want to understand more about this mysterious country.

What followed?

Gradually I got hold of almost all the Japanese literature available in Czech translation. But it still wasn’t enough; so I bought the only Japanese textbook available here in those days and started to teach myself in Jihlava. And there were wonderful [typical Socialist-era textbook] sentences like “Poppies are red” or “Brother, someone stole the hoe.” It was material taught at language schools, but it was definitely not for self-study.

Later you applied for and were accepted at the University of Economics in Prague…

… and I also started going to a language school in 1980. At that time, there were not many people interested in learning Japanese and the school conditioned the start of the course on a minimum number of students, which was not met that year. The quota was five, but only two of us enrolled! That’s why, before my first year at university, I convinced four future classmates that when it came to work placement Japanese was fantastic and that they had to start learning the language (laughs). Most of them dropped out at some point.

Not you. You graduated from the University of Economics and in 1985, an exceptional student, continued in Japanology, doing a postgraduate course at the Institute of Economics of the Czechoslovak Academy of Sciences. How do you remember the days following the Velvet Revolution?

In the days after November 1989, I was contacted by a crew from the Japanese public broadcaster NHK. They asked if I would interpret for them in interviews with key personalities of the Velvet Revolution as well as help with translation. That was a wonderful crash course. I spent the entire turbulent period with their team and got to go places I would normally never have gone otherwise. I saw how reports were filed and sent to Japan and got a look at how the whole media machine operated. Then, in 1991, another chance of a lifetime came my way: a former classmate of mine worked at the Czech embassy in Tokyo and wrote to me that a Japanese university was looking to accept a student from Eastern Europe at their Faculty of Economics. They had one basic condition: the person had to be fluent in Japanese. The combination was ideal. I replied and that was how I got accepted.

Your life must have changed. It did, also because just a few days later, we found out we were expecting twins. And because my brother-in-law is an obstetrician-gynaecologist, he refused to even discuss the possibility of us leaving. So it was with a heavy heart that I returned the scholarship, saying I couldn’t come for family reasons. They weren’t offended. They did something else. At Christmas, ‘my’ Japanese professor called me and explained that if I didn’t come, my scholarship would be forfeited and the university might have trouble allocating additional funds in the future. He promised us all the care of their medical faculty… In the end, we agreed that I would come alone first and, when the children were born, I would bring my whole family. Then, together with our three children, we had perhaps the most wonderful time of our lives in Saga.

After your return, as of the autumn of 1994, you became the head of Japanese studies at Charles University. What was your game plan?

I’ve always been driven by a kind of intellectual curiosity: how things work, uncovering their true nature; the Japanese call it kókishin. My colleagues and I tried to add to the field of Japanese studies at the Faculty of Arts as a basic part of human knowledge that was largely missing at that time: the social science aspect. Most similar courses are accredited philologically, but despite this basic anchoring, the whole field of study ultimately comes down to understanding the country and culture in the broadest sense. If you ask students today what they want to study, they are interested in linguistics or classical poetry, but also in issues of minorities, the crisis of the family in postmodern Japan, pop culture, and economic thought. We therefore rely on the four pillars of our field: language, history, literature and society.

Fortunately, interest in our field remains high: around 150 applicants apply for the Bachelor’s programme each year, of which, unfortunately, we can only accept a maximum of 20. I regret that we cannot take all those who meet the demanding requirements of the entrance exam, and to some extent we are "wasting talent", but I also understand that the university has limits.

You talked about the field. What are your plans?

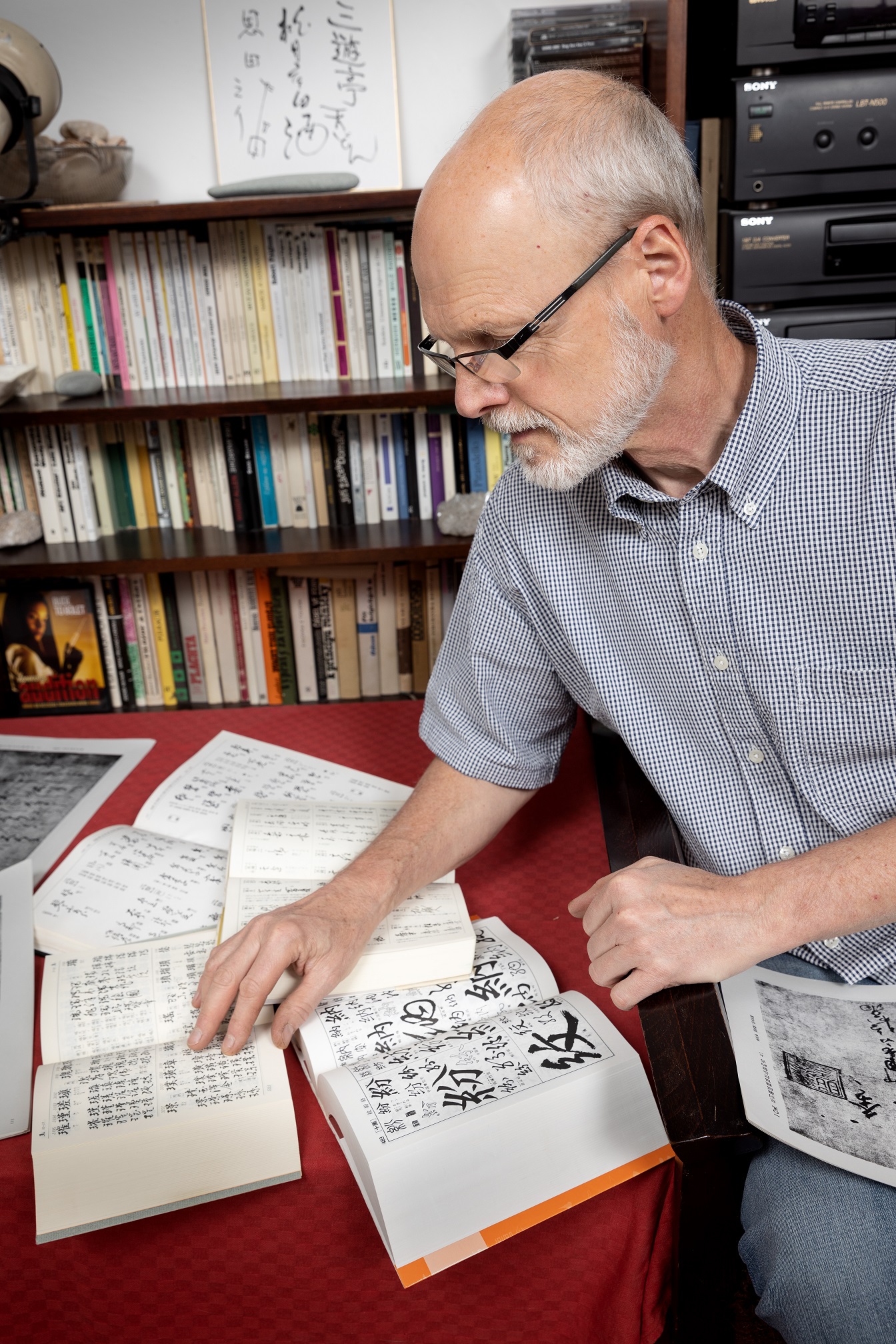

I am preparing the second volume of The History of Economic Thought in Japan, and I have been working for a number of years on An Introduction to Japanese Paleography and Diplomatics. I have collected more than ten thousand photocopies of texts stored in various Japanese archives and am processing them for the purposes of the forthcoming publication.

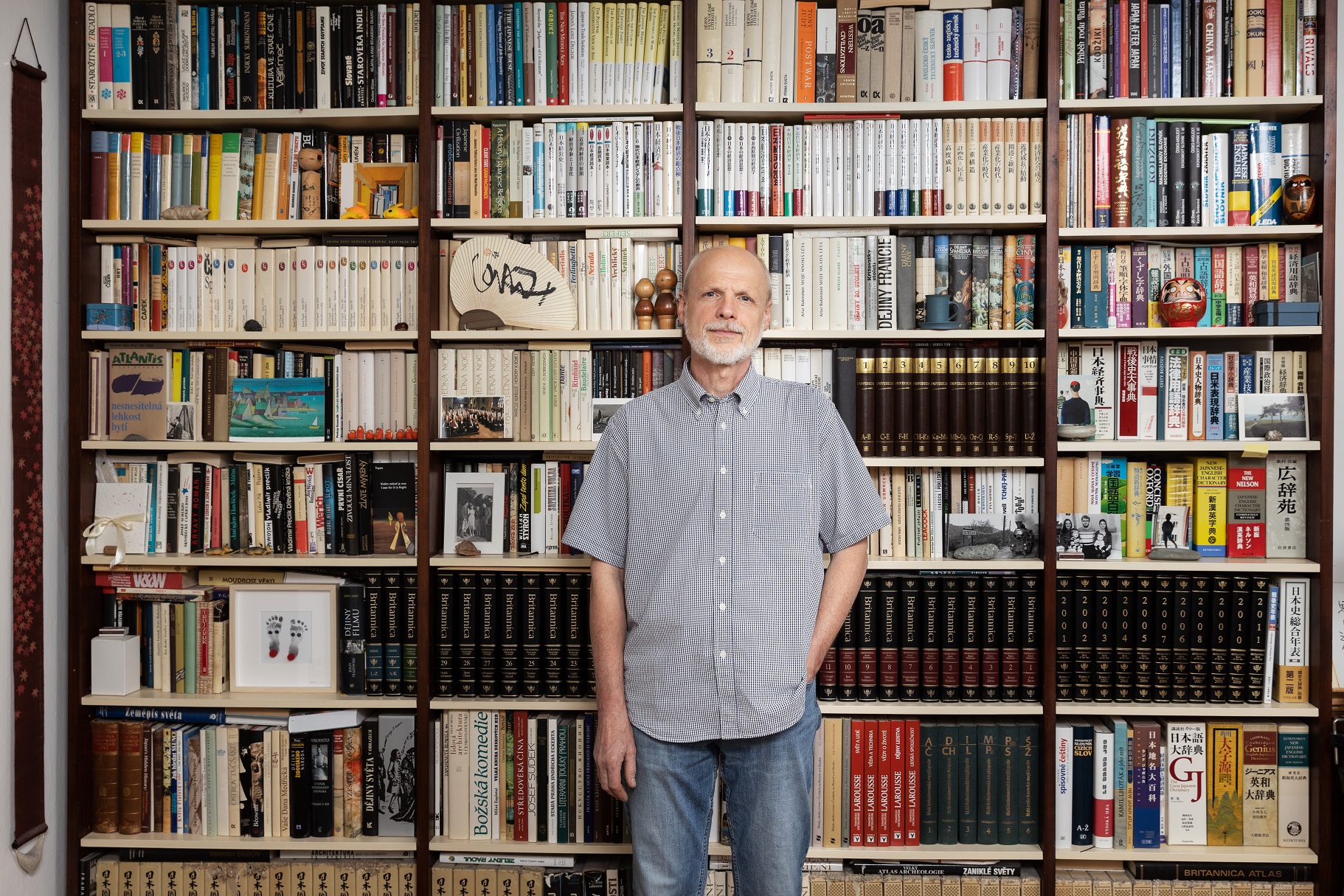

| Associate Professor Jan Sýkora |

| Jan Sýkora comes from Jihlava. He studied at a state language school in Prague taking Japanese language classes taught by Zdenka Švarcová. After the Velvet Revolution, he graduated from Saga University in Japan (1994), completed his doctoral studies at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University in History and Cultures of Asia and Africa (2002) and habilitated in the same field in 2011. From 1994 to 2000 and subsequently from 2006 to 2019, he was the head of Japanese Studies at the Institute of Far Eastern Studies at the Faculty of Arts of Charles University. His research focuses on the socio-economic and intellectual history of Japan as well as on current issues of contemporary Japanese society. He has been a visiting professor at universities in Europe (Oxford University, Universität Heidelberg, Universität Zürich, Lunds Universitet, Vilniaus Universitetas, Jagiellonian University in Krakow) and in Japan (Nichibunken, Osaka University, Kansai University etc.). He is the author of numerous publications and scholarly articles, including the first Japanese-Czech Character Dictionary (2000, co-authored with David Labus) and the monograph Economic Thought in Japan (2010). He has translated and interpreted – twice even directly for the Japanese emperor himself (2002, 2007). |