At present, the Faculty of Science of Charles University boasts a herbarium containing almost 2.5 million items. “Such herbaria (or collections of pressed and dried plant or flower samples) are living archives of plant biodiversity,” says botanist Patrik Mráz – responsible for the collection.

It probably won't come as a suprise that when he goes on holiday, the associate professor usually takes a plant press along to flatten and dry field samples for easy storage. Mráz displayed an interest in botany at an early age and to this day still has his first book of pressed specimens from grade three, remembering where each item was found on walks with his father. Today, his office at CU is stacked from floor to ceiling with files, many housing unique contents. The herbarium he oversees is among the largest and oldest in the world. The rarest samples in the collection date as far back as the late 18th century!

Larvae: The bane of all herbaria

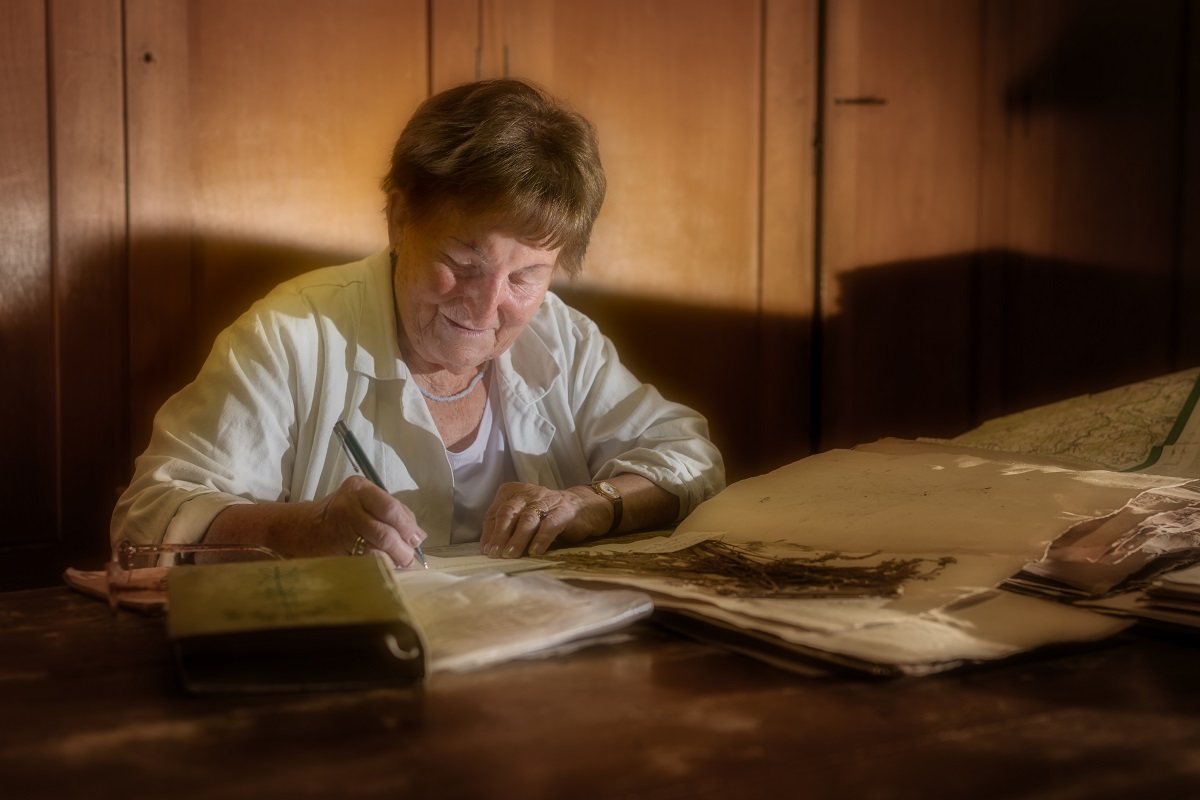

“Yes, it's a paradox. Although the plants are dried, the archive is brought to life by people who keep studying them and need them for their scientific work,” the botanist tells Forum, confirming that there is extensive interest from well beyond the Czech Republic or neighbouring Slovakia, but from all over the world. “We can enrich each other with information on a given herbarium item. Often individual items are described by someone other than the person who collected the plant. In this way, we often discover new connections,” the botanist explains.

Before the individual plant samples become part of the university collection, they are pressed, dried, glued and labelled, indicating the time and place they were found. The complete drying and pressing process takes five to six days, carried out at a temperature of approximately 40 degrees Celsius for a period of two hours, during which the drying equipment is switched on at regular intervals. This allows the plants to retain important characteristics. These can survive even 200 years! That is, if the plants are not attacked by the greatest enemy of herbarium collections: larvae. To prevent infestation, botanists freeze items at minus eighteen degrees for two weeks before they are stored.

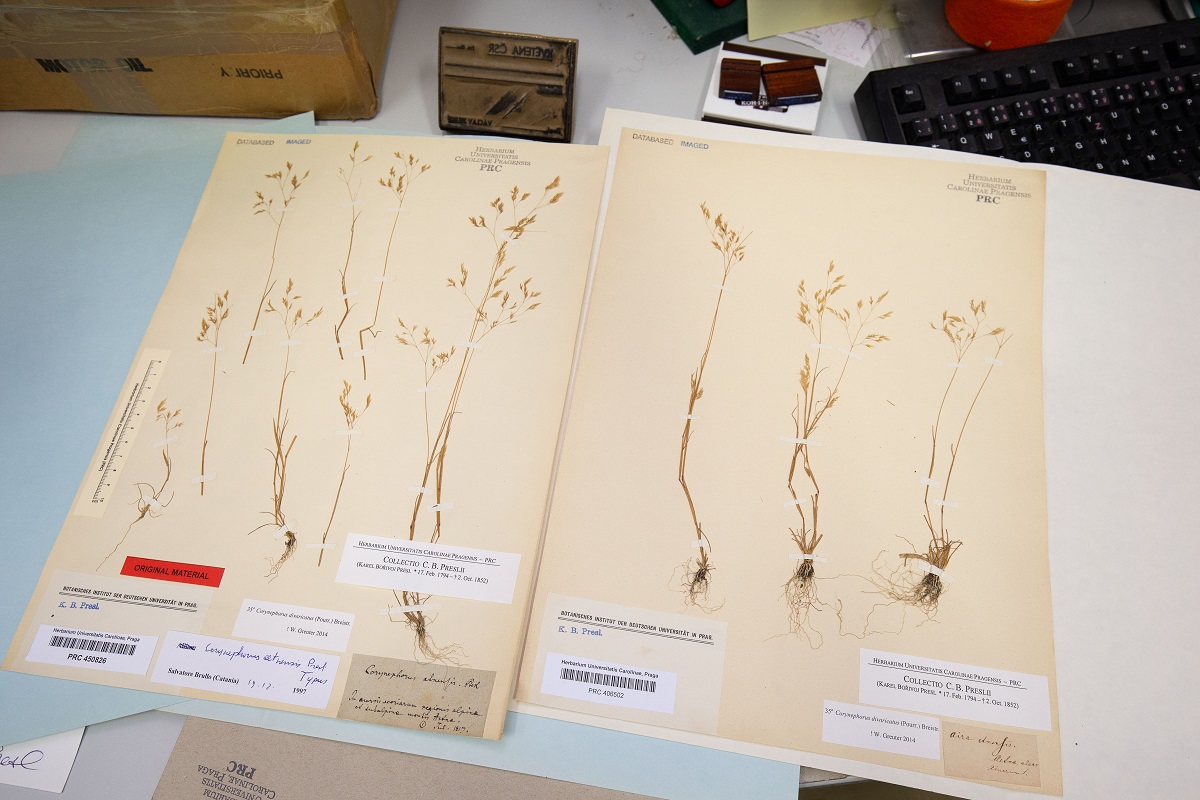

Pressed plants are next glued, often by temp workers helping out in the botany department. Their task is to assemble the items: glue them onto a sheet, attach a barcode under which the item is loaded into a database and thus becomes part of the herbarium. The international acronym of the herbarium is also part of the barcode. In the case of university collections, this is the acronym PRC, which is registered in the international Index Herbariorum, bringing together about three thousand herbaria, of which 54 are in the Czech Republic. The individual items are also scanned digitally.

The ordering of samples follows the same procedure as the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew. The herbarium collection there was founded in 1853 and remain one of the most important centres of botanical research in the world, currently containing over seven million items, including the personal collections of famous British naturalists including Charles Darwin, Joseph D. Hooker and David Livingstone.

Part of the collection is liquid-preserved

Currently, the collection of the Faculty of Science of Charles University boasts almost 2.5 million items, with vascular plants being the most numerous - approximately two million. Another large group consists of non-vascular plants (bryophytes), but also fungi and lichens, and there is also a collection of algae. In terms of size and age, the local herbarium is one of the ten most important in the world, which are managed by university departments. Perhaps surprisingly to the layperson, some five thousand plant samples are liquid preserved.

As a purely scientific collection, access to it is only open to the professional public. “If you come to us with a specific goal in mind and request access, or if a student is interested, then you will receive the necessary training. We often let school groups see the collections as well,” says botanist Mráz. The only limiting factor is the more cramped space; the construction of a new campus at Albertov in Prague, home to the Faculty of Science, would be a welcome relief for the Herbarium, it is clear.

“We boast that ours is the oldest and largest herbarium collection in the Czech Republic,” says Patrik Mráz with a wry smile. The jewel of the collection is that of Thaddeus Haenke (botanist, physician, ethnographer, cartographer, geologist, traveller and explorer; lived from 1761 to 1816) from both American continents and the Philippines. “The twists and turns in his life would make a great Hollywood movie! He travelled then with an imperial recommendation and a promise to return and further research on the material he had obtained. In the end, he stayed in America and died there under unexplained circumstances," Mráz explains the fate of the prominent German-speaking botanist, a native of Bohemia. In America, Haenke joined the expedition of the Italian seafarer Alessandro Malaspina and collected an enormous amount of material. It was he who first documented the world's largest aquatic plant, the Victoria - and also the world's largest tree: the giant sequoia.

| Associate Professor Patrik Mráz |

| As a boy, he spent a lot of time in nature with his brother and father, enjoying botany and zoology. He graduated from the Faculty of Science of the Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice. He completed his doctoral studies in botany at the Slovak Academy of Sciences (SAV) under the supervision of Professor Karol Marhold. As a postdoc, he obtained a two-year position at the University of Grenoble in France. After five years in Fribourg, Switzerland, he was offered by his former supervisor a vacant position in the Herbarium Collection of the Faculty of Science of Charles University. He has been working there since 2013. |