Czechs last week who followed the outcome of the election at iRozhlas.cz as the results came in, benefitted from a predictive model designed by Associate Professor Marek Omelka and Ondřej Týbl from Charles University. With a little over 20 percent of districts counted, the scientists were already fairly certain who had gained a majority in the lower house.

This year’s elections to the Czech Parliament were dramatic. Polls days ahead of the actual vote showed billionaire Prime Minister Andrej Babiš's ANO coming first. But in what was described by domestic as well as international media as a surprise upset ANO - the largest single party grouping in the Chamber of Deputies - came in second in addition to missing a viable path to forming a majority in the 200-member house. The majority was clinched by two coalitions that had formed ahead of the election: SPOLU (Together, a coalition of the centre-right Civic Democrats, TOP 09 and Christian Democrats) and PirSTAN (The Pirate Party and Mayors’ Party).

The results came down to the wire but Associate Professor Marek Omelka and Ondřej Týbl from Charles University’s Faculty of Mathematics and Physics, Department of Probability and Mathematical Statistics, created a unique predictive model for tabulating results, reacting to the latest data as it came in. While other media could rely only on updates from the Czech statistics office throughout the day, the CU model allowed Czech Radio to predict early on the unexpected result. “With just 20 percent of districts counted,” says Ondřej Týbl, “we were pretty sure that SPOLU and PirSTAN would win a majority.”

Forum spoke to Týbl and Omelka to find out more about their model and its success.

What went into the development of your predictive model?

Omelka: First, we had to gain an overview of how votes are counted and to understand that the results from smaller districts come in first, and larger ones, such as town districts, later. That means that the results in smaller districts are known sooner [Editor’s note: in this year’s election that meant ANO, the populist SPD, the Communist Party and the Social Democrats]. As the hours passed, the results improved for parties with greater support in towns and cities, in this case the Civic Democrats, Pirates and TOP 09. Our job was to estimate accurately how much the gains by the latter group of parties would cut into the results of the first.

How did you resolve this disproportion?

Omelka: We relied on a method commonly used when estimating polling, but also elsewhere in sample surveys, where you try to estimate the proportional representation in a much larger population – for example, in the whole of the Czech Republic – from quite a small sample of people, of the order of thousands.

Agencies involved in such surveys compare the known demographic structure of a large population with that of their sample and give different weights to the different respondents in the sample, accordingly. Simply put, if, for example, they find that men are over-represented in their sample, they give them less weight, and in turn they increase the weight for women. We decided to try to do it similarly.

The mathematicans behind this year's highly successful predictive model used by iRozhlas, speaking to the author.

Can you explain this in greater detail?

Omelka: With the help of voter preferences from the last parliamentary elections, we divided the districts into several homogeneous groups - in statistical theory they are called strata. We determined the predictions as a weighted average of the votes already observed, with the weightings chosen to match the actual representation of each strata of districts with that of the stratum across the Czech Republic. This is the so-called ascendancy method. Thus, for example, if a strata's districts make up 10 percent of the voter population, but only five percent in the those counted so far, we will give votes from those districts double weight.

So you had to come up with this before actual voting began.

Týbl: We defined the groups before the election started. During their course, only the weights mentioned were recalculated. As new districts were added, the representation of individual strata changed in the sample already counted, and our model had to be able to respond to that.

How did your predictive model at iRozhlas.cz compare to the running results reported by other media?

Omelka: Most of the media reported the current state of affairs. iRohlas was interested in a predictive model, knowing that the picture as the votes came in at the beginning would be distorted. The districts, as they are slowly counted, do not provide an accurate picture of voting in the Czech Republic. Thanks to us, Czech Radio was able to get a more accurate estimate of how the election would finish. And that estimate was significantly better than the latest results provided to the media by the Czech Statistical Office (CSO).

What specifically was the biggest added value of your model?

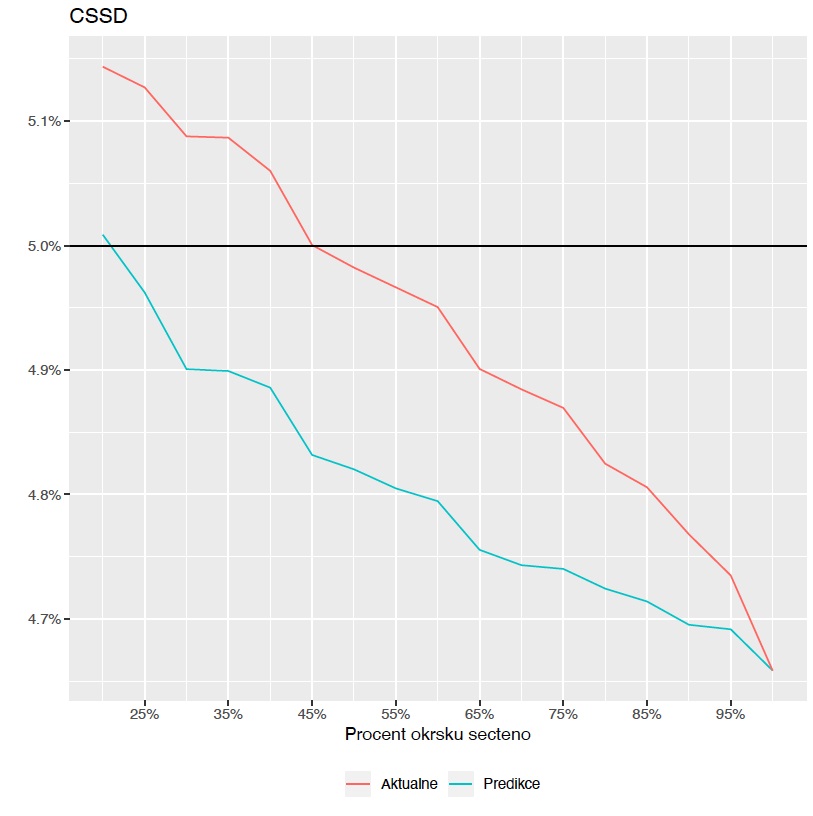

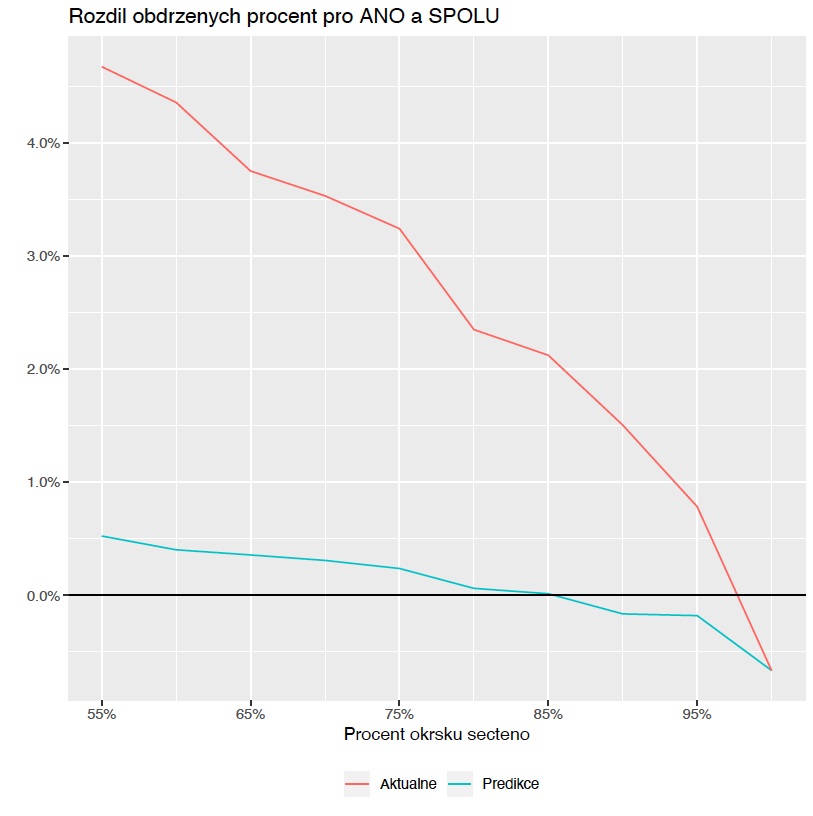

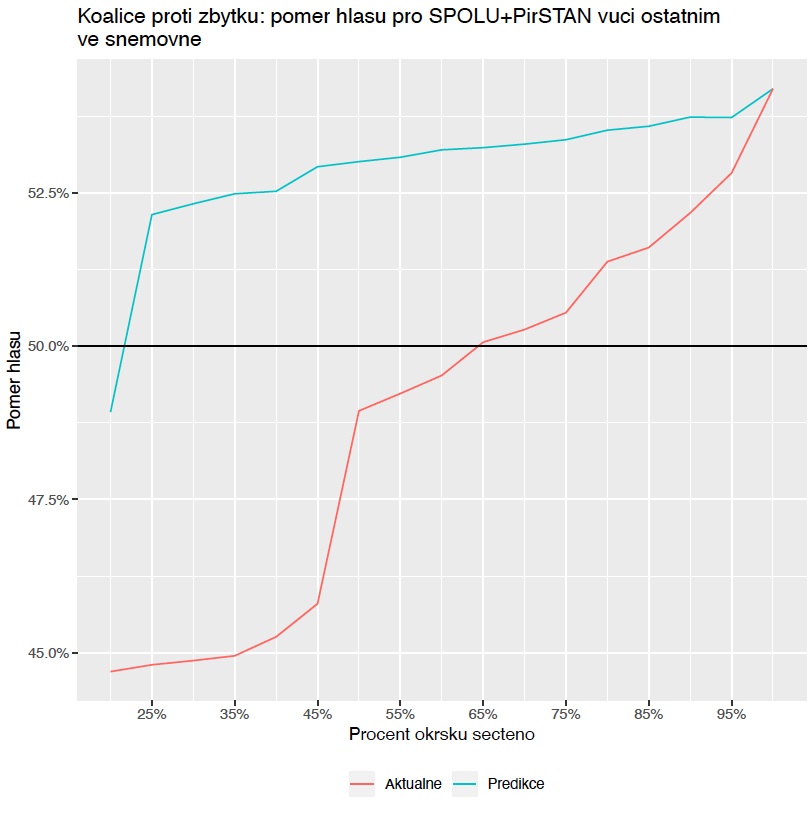

Týbl: I'd mention three points. The first: by the time 25 percent of the electoral districts were counted, we were fairly certain that the resulting coalitions, Together and PirSTAN, would have a majority in the lower house of Parliament. Which was something that was not readily apparent if you were going only by the latest numbers. A lot still depended on whether the Social Democrats and the Communist Party would make it into the lower house [Editor’s note: both failed, with neither party reaching the five percent threshold] and SPOLU had to pick up additional votes before that could be confirmed.

Was it clear to you from your model that neither the Communists nor the Social Democrats would succeed?

Týbl: That's the second point. For the Communists, it was soon apparent even from the actual results, but for the Social Democrats it was evident only after some 45 percent of the districts had been counted. And we saw it a lot sooner. Third, the contest between ANO and SPLOU was also closely watched. At first glance, it was unclear how this would play out even with just three percent of districts remaining. Meanwhile, our predictions rightly began to lean in favour of the surprising winner just after some 85 percent of districts were counted.

The iRozhlas website describes how your model works. Does that mean other mathematicians could use this as know-how to create their own competing model?

Týbl: Key mathematical concepts are given in this description and at the very least it is a good guide for those who understand how they work. They probably wouldn't be able to process it in quite the same way, but would still be well on their way.

Omelka: The method of predominance is well known in statistics theory and is used by experts who do population surveys. What is most difficult in our model is to find homogeneous groups – that strata – electoral districts in which people vote similarly. And then you have to think about how many strata to use. In theory, the process is pretty clear, but, as they say, the devil is in the details of implementation. And I'm so glad Ondřej went along with it. He really tinkered with it and took his time.

Týbl: I implanted ideas that Associate Professor Omelka brought in and made them into a code, or a mathematical model.

Omelka: It's certainly not that Ondřej just programmed something I told him – it's not that simple. During the programming, he came in and raised a number of issues, such as changes in the size of voting districts. He produced a series of ongoing analyses, on the basis of which we gradually worked out the essential details.

Do you plan to prepare predictive models for other uses?

Omelka: We would probably do so again; if there is interest from Czech Radio. We both like this collaboration between Charles University and public media, which does serious reporting, plus quality data journalism. But of course it's a big commitment and responsibility for us because, especially with this kind of real-time prediction, one mistake could cast a bad light on our faculty or Charles University. And we'd hate it if that happened.