Kateřina Chládková is one of the few researchers in the world who study the earliest stages of language acquisition, which means she is often in contact with babies – even in the maternity ward. Her aim is to find out how we learn to speak from the very first moments of life. Thanks to CU Primus programme funding, she and her team discovered that babies learn to differentiate vowels and their length even before birth. In other words, while still in the womb.

Researching the “language of babies” sounds like an oxymoron. A contradiction.

It’s true, babies can’t tell us very much by speaking (laughs). What we do, is research their brain activity, their EEG signals, or monitor how they respond to different sound sequences by looking or moving their heads. This is only a small part of the project, however: our research goes much further, incorporating computer modelling, programming and statistics.

How did this project get off the ground?

I had worked on speech processing and learning in adults and older children since my master’s degree in the Netherlands, but I was very attracted to how we acquire language at the earliest age. Only a few labs are focusing on this subject, yet it is crucial: language differentiates us from others and defines us as human beings. Having a better understanding of early mother tongue acquisition could even help with how we learn foreign languages in the future. Back when I was doing my doctorate, my advisor and mentor asked me where I saw myself in five years. I automatically replied that I wanted to set up BabyLab in Prague. I was able to do it two years ago because we got Primus funding from CU.

What is it like working with babies?

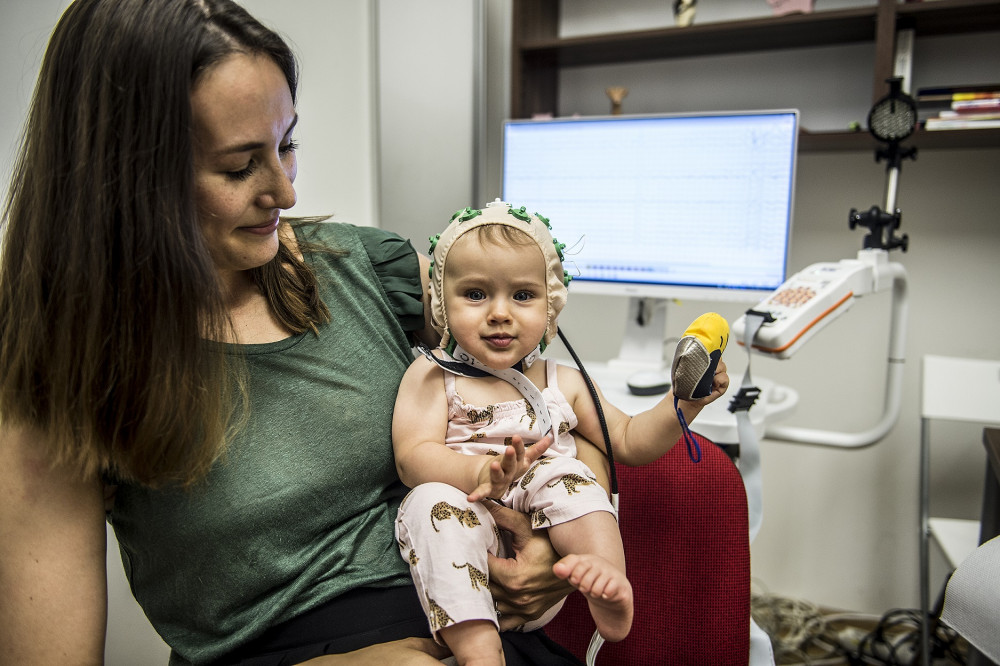

It depends on their age. In one project, we focus on newborns in maternity wards. We take the babies and their mothers to a quiet room, where they get a cap with electrodes and special headphones. We then play various sound sequences and measure their brain activity. Newborns sleep through the whole experiment while their mums read or do something else. Older children, who no longer sleep as much and are much more active, are invited to our laboratory, where we play them various sounds and pictures, and watch how they react, looking and moving their heads.

Generally speaking, what do we know about early language acquisition?

So far, relatively little. There aren’t very many research teams looking at acquisition from an early age. We are also the only ones studying the acquisition of Czech in such small children. Previously it was thought that babies were born as “universal listeners”, tuned only to the native rhythm and intonation and that they acquired the specifics of their native speech sounds, recognising the vowels A, E, I, O, U in Czech, a bit later, during the first six months to one year after birth. What we learned in our project is that they actually start to learn them in the womb. It is also known that newborns can distinguish the voice of their mother from an- other woman’s voice. Babies can also distinguish the mother tongue from foreign languages or other sounds. Newborns even cry in the melody of their mother tongue: French babies cry with a rising intonation, while German babies have a declining one.

Are there any elements that are specific to Czech?

Compared to other languages, Czech is different in that it distinguishes vowel length: the words rada and ráda have completely different meanings [Editor’s note: rada means advice while ráda means to like or love]. And that then makes it hard for Greeks or Spaniards to learn Czech. In Spanish, casa and cása have the same meaning. What we learned is that Czech children start to distinguish not only vowels, but also this length difference, even before birth.

It’s amazing that you are able to map this; could you describe it more?

We play the babies various sequences – non-specific sounds, phrases, syllables, but also whole words and sentences – and from the EEG signals we evaluate in retrospect whether their brains reacted differently. We also model and simulate many things on computers. Not everything can be measured directly. In addition to linguists, neuroscientists, pediatricians and psychologists, our team includes physicists and computer scientists.

Are there languages that are actually “harder” to learn?

Not one’s first language. Of course when learning other languages, it depends on how similar the native language is to the new one. Czech is “into- nation monotonous”, which is why it’s more work for us to come across well in English. At the same time, it shows how important it is to sound good. For example, children prefer to play with children of the same dialect. According to other research, it also turns out that people trust those with a foreign accent less… This would be a huge disadvantage in the context of the coronavirus pandemic and online scientific conferences, where body language isn’t visible and you only rely on sound. After all, wartime spies focused particularly on the flaw- less pronunciation and prosody – the melody and rhythm – of foreign languages in order to blend in.

Can you give some advice on how to best learn a foreign language?

Like a baby does – listen, observe and try to understand a foreign language situation in a real context. And ideally you won’t even speak for the first six months, and definitely not read and write. Then you pick up the accent and a feel for the language like a native speaker. But I understand that that is a highly impractical way to do it: there aren’t many people who have that kind of patience or time. Of course, an accent can be re-learned but it takes much more effort.

Is there such a thing as “being wired” for foreign languages?

A musical ear helps when learning languages. But one doesn’t have to be a trained musician at all. It’s enough to have an ability to perceive rhythm and melody. Correct intonation is more important for listeners than flawless grammar. That’s why Dutch people sound like native English speakers even if they make grammatical mistakes: both languages are rhythmically and melodically similar.

What about bilingual families? How does speech acquisition work in those cases?

There had long been a belief among pediatricians and speech therapists that children should not speak two languages because it was said to cause delayed development. Fortunately, this has been refuted. Bilingual children may have a seemingly slower start because their vocabulary is divided into two languages. But they soon catch up and they have lifelong benefits from it.

Would listening to foreign language recordings during pregnancy help?

This is exactly what we plan on focusing on in one of our upcoming research projects. It may help if a woman regularly speaks two languages during pregnancy. Theoretically, listening to recordings in foreign languages every day could also have an influence, but scientists still have to verify this empirically. But if a child is really going to acquire more languages, they must be exposed to them after birth as well, and in a social context, which means in communication and interaction with a real per- son. Mere recordings will not be enough.

What are your next plans?

We’re getting ready to study the influence of dialects. In the case of premature babies, we will research when exactly in perinatal development humans start to learn about the individual sounds of their mother tongue.

What do you see as the limits of your research? What are some limitations?

Not having enough babies (laughs). This was one of the tricky parts in the Netherlands, for example. In the Netherlands or Great Britain, you go home a couple of hours after giving birth, so almost no research into speech in newborns takes place there. In the Czech Republic, parents have so far been quite passionate about this local and new research and we’ve had no lack of volunteers so far (well until the epidemic locked everything down of course). That was a very nice surprise for me. It’s also an advantage for us that it’s common in the Czech Republic to stay in the maternity ward a couple of days after giving birth, which gives us room to conduct research.

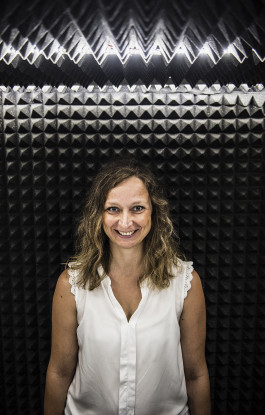

| Kateřina Chládková, Ph. D. |

| Kateřina Chládková works at the Faculty of Arts and at the Institute of Psychology of the Czech Academy of Sciences. She spent many years abroad at universities in Amsterdam and Leipzig. Thanks to internal support from the CU Primus programme, she leads a multidisciplinary and unique team studying the acquisition of language from the earliest age. |