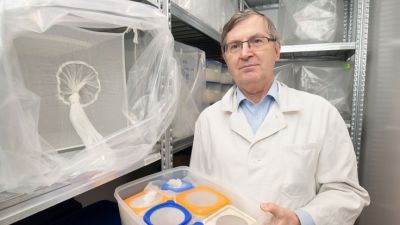

Sleep is Karel Blahna’s focus of research. At the Biomedical Center at Charles University’s Faculty of Medicine in Plzeň, he looks into how the brain’s sleep activity changes in sickness and health. He was able to put together a team and conduct research thanks to support from CU’s Primus programme.

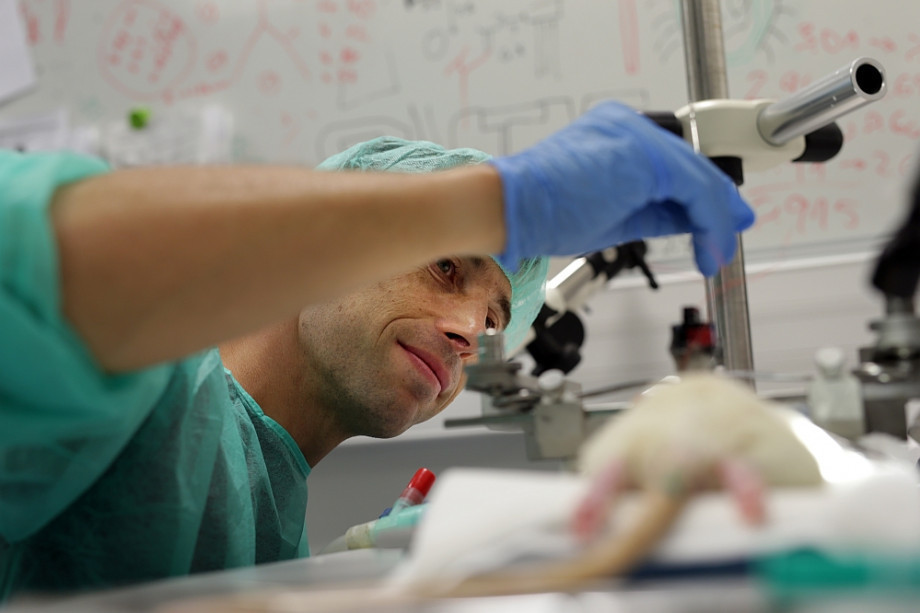

Karel Blahna in the lab in 2020.

Even as a medical student, Blahna was fascinated by sleep – not as a state of rest but as a state of neuronal activity, in which certain parts of the brain, such as sensory inputs, are turned off. “In sleep, the brain works in a different mode, and there can be various pathologies and differences between a healthy brain and a sick brain,” he says. A correct understanding of the mechanism of diseases is key to a better understanding of the illness and possible treatment.

Alzheimer’s disease

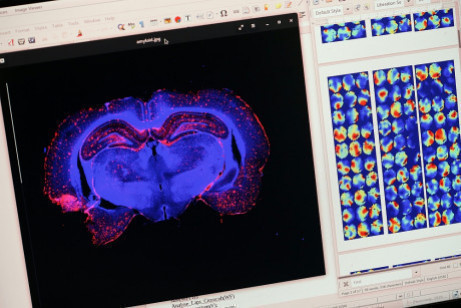

In his research, Blahna focuses primarily on the study of Alzheimer’s disease and schizophrenia. “We measure brain activity at the level of individual neurons in the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex in laboratory rats,” he explains. The hippocampus plays a key role in learning – especially in episodic memory – meaning for events in the context of place and time. During sleep, information from short-term memory in the hippocampus is then stored in long-term memory in the cortex.

“In animals with Alzheimer’s, we expected a disruption of activity of place cells during their actual movement in the environment. Instead, what we found was that significant changes did not occur until playback during sleep. In healthy specimens, the entire trajectory of the run was played back – the complete information was stored. But in sick animals, only short fragments were played back,” the scientist confirms. The Pilsen team focuses on a certain type of cells – hippocampal pyramidal neurons called place cells – that specifically activate depending on the environment. The place cells’ activity then forms a special cognitive map (a map of one’s environment stored in the brain), according to which it is possible to determine retroactively where and how the animal moved during waking hours.

“Animals play back information about how they moved in their environment in their sleep: you could say they ‘dream’ about it – and that’s what we measure,” the neuroscientist says. “When animals are in a new environment, the new information is played back more intensely. We also know this from everyday life: a new environment is a much stronger stimulus for all of us than our everyday commute to work,” he explains. In experiments, scientists first monitor the activity of animals’ brains when moving in a new or already familiar environment, and then compare this record in samples of animals that are healthy and sick. In their sleep, they observe how this spatial memory, encoded by the activity of the place cells, is reactivated and replayed.

Gaining experience abroad

Blahna describes himself as a neuroscientist-physiologist who enjoys learning how the brain works, but at the same time wants the new knowledge to be useful. Which is why, in addition to basic research, he works together with his colleagues, Karel Ježek and Petr Telenský, to research new drugs. How he spends the day in the laboratory varies depending on the phases of experiments. “Our experiments include training animals before and after they are operated on for study, the measurements themselves and then the subsequent processing and analysis of data, which often takes considerably longer than the experiment itself,” he says.

Working with laboratory animals – especially sick specimens – requires a fair amount of patience: “The measurements themselves are technically demanding and require a lot of time. In addition, we study older rats that suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, so they remember poorly, have difficulty learning and sometimes just don’t feel like exploring their surrounding environment,” he says about the sometimes humorous woes of laboratory work. But he wouldn’t trade lab work and conducting experiments for anything: “I enjoy being able to discover all sorts of things and I learn something new every day.”One recommendation for any student considering a scientific career? Hands- down, experience abroad. He himself spent five years as a post-doc at IST Austria. Eventually, an offer from his former teacher, Karel Ježek, now his friend, was too interesting to turn down, so he returned to the Czech Republic.

Sleep is beneficial for the scientist, too

Another recommendation? Changing majors during one’s studies, or at least getting interested in other fields, in order to gain a broader overview beyond one’s “bubble.”“I didn’t need long to decide. The Biomedical Center is a modern institution. It has excellent equipment, there are a lot of great students and scientists there, and they speak English because there are also a lot of foreign colleagues,” he says. “Thanks to Primus, I can continue research I started abroad,” he adds.

According to Blahna, it is important to have other activities beyond science: “You don’t get innovative ideas or find solutions to complex problems only in the lab: they also come when I’m out in nature, when I’m riding my scooter or doing artistic work.” Art is his passion: he is a photographer and is learning to do drypoint printmaking. A few years ago, he started learning piano – just for fun. “I used to write short stories, but I no longer have the time. Now I spend my free time with my family and children,” he says. Interestingly, he sometimes sorts out outstanding problems in his sleep. “I think I somehow programmed myself to do that, thanks to my research,” he says, laughing. He adds that he has to write down new solutions immediately after waking up otherwise the idea would dissipate and be lost. He also has plans in his head for new scientific publications he has to figure out. “Getting Primus internal support was a major commitment and until I’ve completed all the publications, I won’t sleep easily,” he says with a laugh.

| Karel Blahna, Ph. D. |

|

Karel Blahna works at the Biomedical Center at the Faculty of Medicine in Plzeň. He spent five years as a postdoctorate researcher at IST Austria. He received internal CU Primus support for his research into the sleep dynamics of neural networks in sickness and health. |