Next month it will be a year that Czechs first went into lockdown because of Covid-19. According to one non-scientific study, alcohol consumption rose slightly among some 20 percent of Czechs and six percent significantly, as they grappled with the effects of the pandemic including financial instability, the loss of jobs and fear of catching the virus.

Not this month: organisers involved in Dry February hope Czechs give alcohol a pass over the next 28 days.

Not this month: organisers involved in Dry February hope Czechs give alcohol a pass over the next 28 days.

This month also sees the return of the Dry February campaign that challenges participants to abstain for 28 days. I discussed the campaign, alcohol abuse and the pandemic with Dr. Miroslav Barták of the Department of Addictology, First Faculty of Medicine, Charles University in Prague and General Faculty Hospital in Prague.

Dry February, an NGO-run operation, is in its ninth year - how important a campaign is it?

Many people know Dry February quite well now and it has been quite a successful campaign, which has sunk in and even become a part of popular culture, used, for example, in unrelated advertisements. The aim, above all, is to raise awareness and it’s a challenge: a positive social challenge asking people to give up alcohol for a single month a year. To not drink at all and see how one feels afterwards: it gives you room to reflect on occasions when you drink and to consider the pros and cons.

There are many benefits to not drinking for a month: you can save a bit of money (perhaps more important in the year of the pandemic than ever), you can gain a better outlook or perspective on your life, problems related to the pandemic and otherwise may be more manageable without alcohol. In terms of health, you may sleep better, skin quality improves and finally there is social recognition: accepting a positive challenge at a time when most challenges we face are negative.

More and more people, at least before the pandemic, were becoming more careful about their health – from what they ate to being physically active: the running boom is one example. So it makes sense that there is room for this kind of challenge. What about the next step? Is there a bump in the number of people who contact the addictology clinic who, after having taken a break, re-evaluate their life situation?

This is not an easy question to answer because while awareness campaigns highlight issues, the journey whereby individuals recognise they have a problem requiring them to seek treatment is a long one. There are many people who have drinking problems but at the end of the day who are not clients of any addiction services. What we can offer is this: at our website https://www.adiktologie.cz/en there is a famous and internally acknowledged screening questionnaire called Audit (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test) that helps determine whether someone has a problem or not.

Normally, about 4,000 people a year take it; but in February that number jumps significantly – February has the highest number. Additionally, interest in getting more information goes up as does interest in counselling at the website as well as the number of calls to the national helpline. So Suchej únor or Dry February helps: it can help people who don’t have a problem yet re-evaluate their situation and to make adjustments on their own, or it can be a contributing factor helping other realise their problem is more serious and to begin looking for solutions.

Are campaigns like this common in neighbouring counties or further abroad?

Other countries have similar campaigns but many of them can’t be compared directly because of different variables: the great thing about the Czech version is that it is in no way related to the alcohol industry or any competing interests: it’s purely an NGO campaign supported by public funds. As far as similar initiatives in other countries, the UK, for example, has Dry January, Australia has Ocsober, we have followers in Slovakia and definitely there are sobriety campaigns mentioned among other states of the OECD; but each is different – there is no set common methodology or variables which would make it possible to measure and compare the campaigns. It’s all still very much a grass roots effort built from the ground up, which is generally a great thing.

If we talk about alcohol as a serious problem, most will be aware that alcohol consumption is quite high in the Czech Republic, among the highest in Europe. What are some of the signs – for individuals or their families – that someone’s drinking is getting out of control?

That isn’t an easy question but in a clinical setting it takes up to one year to determine whether there is an addiction. But certainly there are warning signs: one of them is craving and an uncontrollable seeking of alcohol and desire to consume. That overrides negative effects in one’s life. If you neglect or lose interest in everyday activities, and the only important interest becomes drink. If your relationships are suffering and relatives or people close to you begin telling you that you have a problem. If you become unable to fulfil regular social roles that were not hard before. If you lose the ability to resist even though it leads to problems. If you need more and more of the substance to reach the same level of short-term positive experiences that alcohol provides.

Others signs include whether you need a drink already in the morning, if you don’t remember the next morning the events of the night before, if you drink alone (although that is harder to evaluate in the middle of a pandemic). A serious evaluation is always needed: a single one of these factors, on its own, does not necessarily mean a person is alcohol addicted.

Once someone learns that they have a problem, quitting isn’t as easy as just throwing out bottles and having a dry household, and thinking one has made it, correct? It’s a multi-layered process where there are many steps along the way and I suppose clients who have sought help need support and positive reinforcement and also to find things to replace drinking in their lives. Is that the case?

It is good when people who realise they need help to look for addiction services to help: it is not possible to overcome this problem by one’s own will alone. Motivation is important during the treatment or healing process of course but after 90 days of treatment, there is still a danger of relapse and generally speaking the first year after treatment is very important. The main thing is that people have to want to really change. There is not much you can do if the person is unwilling to change and there is a definitely a gap between those who really need help and those who actively seek it.

What was the situation before the pandemic struck? Were there positive signs, if we look at underage drinking for example?

There have been a number of positive changes, not least among youth, even during the pandemic. Underage consumption has been going down; on the other hand, other addictions, such as internet addiction has gone up. But we have to take into account that this positive trend has been seen in the data before the pandemic. But in terms of general drinking, according to international data, there has been a stagnation or just very small growth let by unrecorded alcohol consumption estimation, however the data also reflect much more about the situation before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Many good things have been taking place in terms of alcohol policy, including recent efforts in limiting alcohol advertising. Covid-19 of course changed public health priorities a great deal but alcohol abuse is still high. There are several thousand alcohol-related deaths annually but even there you have to distinguish between fractions: alcohol can be the 100 percent reason someone dies from alcohol liver cirrhosis, but there are also many cases where alcohol is a contributing factor. It is a complicated question to answer.

One thing that has gained increased attention in recent years are links between alcohol and cancer. Cancer is not the first thing people think of when they think of alcohol and many underestimate the possible long-term consequences. It is important to highlight these issues over and over again. If we talk about treating alcohol addiction, the step of quitting is not easy: there are withdrawal symptoms, clients don’t feel well. But the long-term benefits come to the fore eventually. Treatment is the reverse of alcohol use: if you drink you feel good in the short-term but eventually long-term consequences come into play; if you quit, you don’t feel healthy at first and it is hard to get through it, but you feel much better eventually.

It is well known that you do not drink. Given that drinking is a part of Czech life, in everything from socialising to even business dealings on occasion or at least upon the completion of a project, I find sometimes people have a hard time understanding when someone says “No thanks” and there is some push back, although I think the situation has improved a great deal.

It has changed a little; certainly, there are countless situations where saying “No” can be complicated. If friends fail to understand, the question, the elephant in the room becomes, are they good friends at all? The number one best thing you can say, if you want to keep things simple, is that you are driving. If someone insists on handing you a drink, there is another alternative: just set it down soon after, as people rarely notice afterwards what you do. That is if you need a strategy or want to avoid just telling someone or discussing it. If there is an alcohol incompatibility, as I call it, you can also just drink an alcohol-free alternative. It’s “monkey business” sometimes, for sure and for example people previously treated with alcohol addiction are advised not to drink at all - even for example non-alcoholic beer (up to 0,5% alcohol volume).

From my perspective, not drinking does not disqualify me from anything. If you drink, it seems that “everyone drinks”. If you don’t, you see things differently. For example, I was at a conference where there was a wine tasting after where there was a sommelier who was curious why someone wouldn’t drink at all. We talked about that more than how she felt about the wine and we had a good conversation.

If you ask me why I don’t drink, I never had any problems or issues with alcohol, however I am definitely not a lifetime abstainer, I dramatically reduced alcohol consumption when I was 30 and in the last five years I did not drink at all. There were multiple reasons for it, I had become a father and my children were a priority. Last but not least I am also a passionate car driver and drink and driving don’t go together at all, obviously. I also try to be authentic in my work and it would also be hard for me to professionally advocate not drinking and to warn about the dangers of alcohol… and then drink myself.

We having been living through the pandemic for a year now: has drinking increased? Because, on the one hand, pubs have been closed for much of that time, but on the other, people are suffering from isolation and loneliness at home, which can be a trigger.

Different studies using various methodologies have been undertaken, but what I did was have us take part in an international survey of 21 European countries, with around 1,500 respondents from the Czech Republic. It is a non-representative study for the Czech Republic, but 1,500 is not a bad number. In the spring we didn’t see any major changes in the volume of consumption but people definitely changed their habits: they shifted from drinking at pubs or restaurants, which were closed, to drinking at home.

If you have a look at recycling containers in Prague or even small villages, you will notice that the containers for glass are often full. So when we begin to get more information from 2020, I think it will bear out that people have certainly continued drinking and some of them began drinking more. We will also get clearer numbers: national statistics for alcohol consumption will not include many foreigners this year because of the restrictions.

In the event that the numbers have gone up and more people will need help, we are ready to meet the challenge. I think there will be many who need help, after the tough period it has been. If someone works in academia they may have a steady pay check and can work from home that is one thing, but that certainly isn’t the case for many professions and sectors of the economy where people have suffered. Some in the medical profession have been working very long workweeks and have suffered a lot of negative stress. Along with negative stress, a second factor is financial instability in many professions and then, families are not always supportive. All kinds of factors can lead to an increase and I think there will be an impact in the coming years where more people will need our help.

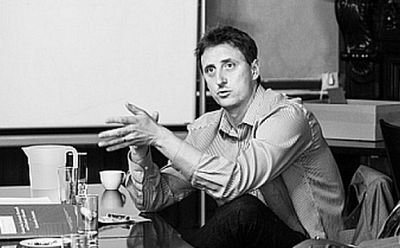

| Miroslav Barták, Ph. D. |

| Miroslav Barták studied at FSE UJEP in Ústí nad Labem and later at the Faculty of Social Sciences of Charles University. He has been working at Charles University’s First Faculty of Medicine and General Teaching Hospital in Prague, in the Department of Addictology since 2010. Dr. Barták is a research fellow there and the head of Public Health Centre for Alcohol Related Harm since its establishment in 2017. He regularly publishes papers dealing with different aspects of alcohol use, is an investigator and team member of multiple research and public health project in the field of alcohol. He cooperates with international organizations like WHO or the OECD. He is now involved in developing a prototype of an Animated Alcohol Assessment Tool (AAA) for facilitating screening and brief interventions for the WHO European Region or on the implementation of the Second Standard EU Alcohol Survey in the frame of the DEEP SEAS project. |