Students interested in space technology and research in the space industry recently had a rare opportunity to attend a lecture by Czech-born scientist Aria Vítková, who completed her PhD in instrumentation for space research at the University of Southampton, following a master’s in Aeronautics and Astronautics/Spacecraft Engineering. Now working at NASA’s renowned Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Vítková has contributed to numerous major projects, including JUICE (ESA) and Lunar Gateway (ESA, NASA). Currently, she is developing instruments capable of detecting signs of life for the Europa Lander, which may one day explore one of the most famous of Jupiter’s icy moons.

Scientist Aria Vítková at Didaktikon in Prague in December. She is designing instrumentation capable of detecting organic molecules on icy worlds.

Students at the Didaktikon Centre at Kampus Hybernská had the unique opportunity to hear first-hand what it takes to study and succeed in Spacecraft Engineering from someone who has excelled in the field. Aria Vítková chose to pursue her dream abroad after finishing high school, leading her to the UK and eventually NASA. Her insights on preparing, applying, and navigating hurdles in the competitive space industry are invaluable for students and aspiring professionals. Opportunities in this field, she noted, are only expected to go up.

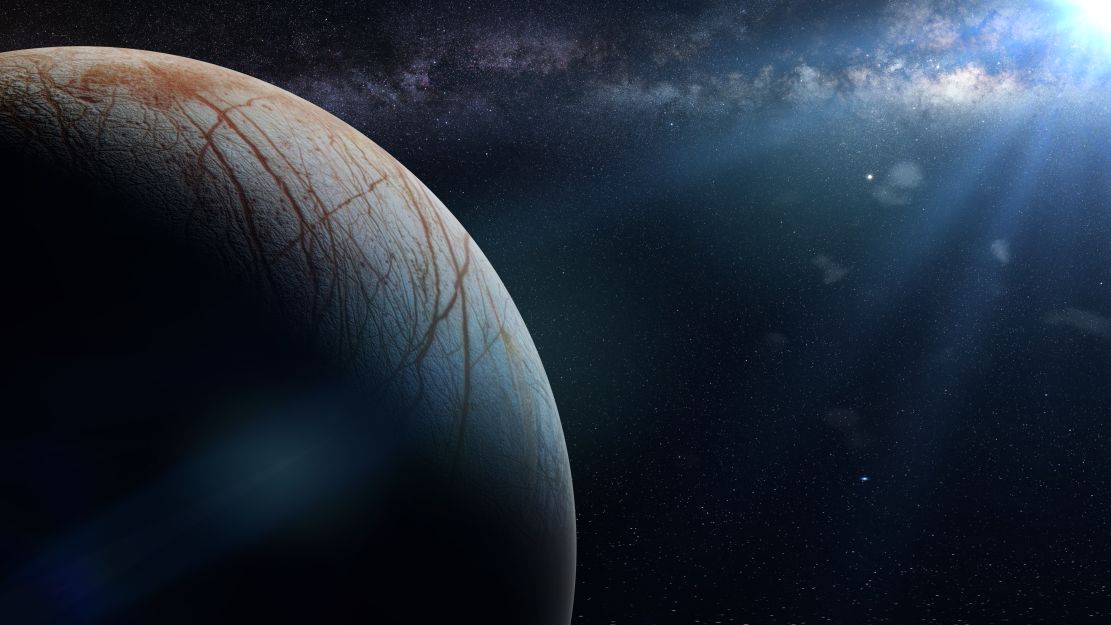

Opening her lecture, Vítková discussed the instrumentation she has been involved in designing and testing—magnetometers, radiometers, and Raman spectrometers—for both mineralogical missions to the Moon and detection missions to icy worlds like Europa, Titan, and Enceladus, moons of Jupiter and Saturn. These celestial bodies are considered candidates in the search for precursors to biological life, including basic organic molecules like amino acids, or even microbial or bacterial life itself, which could exist in subsurface oceans kilometres below the ice. The big question is whether any of these could be detected much further up: the ice on Europa could be more than 30 kilometres thick. Any detection of a biosignature or microbial life would be a major discovery. Secondary data, as well, could be hugely significant, especially given the extreme conditions, revealing more about the icy moon.

Dr Vítková described the immense challenge of developing and testing reliable, sensitive instruments capable of surviving and meeting the task at hand:

“A lot of instrumentation is useless on a world that is ‘only’ ice or water… the thickest ice on Earth is three kilometres, while on Europa it’s estimated to be between 10 and 35 kilometres deep. If there are any amino acids, they will likely be in the subsurface ocean, which means they somehow have to reach the surface. The concentration of biomolecules there would be minuscule… identifying that kind of concentration is a problem for most instruments.”

If the Europa Lander descends without a hitch, it will have just 22 days to operate before succumbing to surrounding radiation from Jupiter or the volcanically active moon, Io. The lander’s task includes drilling 10 centimetres into the ice sheet to search for molecular concentrations. Vítková explained that she and colleagues had had to enhance existing Raman spectroscopy to meet this challenge:

“Regular Raman spectroscopy wouldn’t be sufficient in this case, which is where I come in: I am working with technology called Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (SERS).”

Europa is an icy moon similar in size to our own. Scientists hope to try to detect organic molecules by drilling ten centimetres into the ice.

Europa is an icy moon similar in size to our own. Scientists hope to try to detect organic molecules by drilling ten centimetres into the ice.

For icy moons, even SERS requires modification. Vítková described developing a highly sensitive in-situ Raman spectroscopy method capable of withstanding harsh conditions to detect trace organics in salty ice. The scientist again:

“We came across a glass slide of silver chloride that had been sitting in a drawer at NASA for 40 years. Testing showed this material could be used effectively as a simple and inexpensive means of detecting molecules in extreme conditions. You could combine it with regular instrumentation without adding complexity to detect molecules in very low concentrations. That is my job and the goal of my research: to detect relevant molecules on icy worlds.”

Meeting such challenges is a core part of Vítková’s work: preparing instruments that can survive a landing, function on inhospitable surfaces, and deliver sensitive readings, all within crushing constraints. She showed graphs demonstrating how less advanced instrumentation would miss evidence in the ice entirely. Such projects also require patience and perseverance. The Europa Lander, currently in the concept phase and relying on data from the Europa Clipper, is expected to launch between 2025 and 2035 and will take about six years to reach its destination. If the project goes ahead at the bottom of the decade, it is conceivable raw data would be compiled and reach scientists at some point in 2041.

Attendees were able to ask questions about how to prepare for exams, which literature to read, and how to start a career in space engineering.

Many will recall the risks of space exploration which came to a fore just four years ago during the Mars Perseverance rover mission in 2020, where the rover and its helicopter, Ingenuity, not only landed safely but exceeded expectations and timelines. A similar success on Europa would be very positive and potentially a gamechanger, to say the least.

Reflecting on her work and creating reliable and robust instruments for such a pursuit, Vítková agreed along with rigorius scientific testing, creativity was also essential:

“Creativity is part of the equation. Engineering means being creative within a set of limitations, with a final product that is not a piece of art but must be functional —it doesn’t need to be pretty, but it needs to work. I know many engineers who are also very creative on the side: musicians, artists. I like to draw, I’ve been doing ballet since I was three, and I play violin.”

Keep an eye out for future lectures from Aria Vítková and her return visits to Prague or other cities. She is very pleased by programmes now available at technical universities in Czechia and expressed interest in further cooperation.

“A number of universities asked me to let them know when I’ll be back, and I’d be very happy to do something. It’s wonderful that there are so many opportunities now. [As a student], I didn’t have the same chance—I had to go study in England. Because of that, I’d be very happy to participate.”