"One of the panel members made everybody chuckle during the interview when he said that I had cleverly designed a project on the joys of what most of us do most of the day - and what everyone would like their children to find pleasure in as well," says Anežka Kuzmičová. She has won a prestigious ERC Starting Grant of one and a half million Euro for a five-year research project exploring children's affective engagements with facts and nonfiction, making her the first ever recipient of an ERC grant in the Social Sciences and Humanities at Charles University.

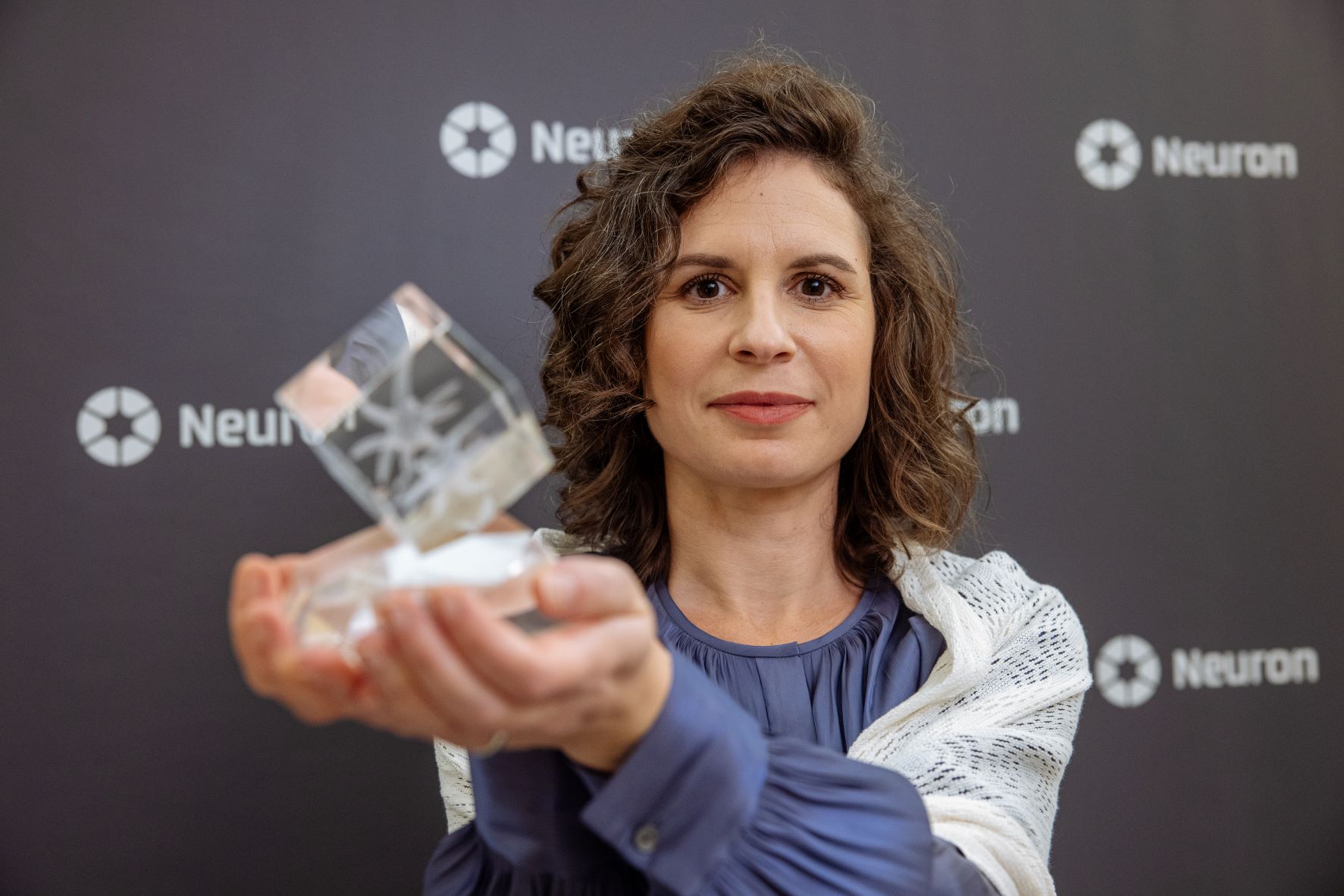

What makes some children indulge in reading space encyclopaedias or football player biographies? And how can we best incorporate nonfiction reading in school-based learning and open it up for children who cannot access such books elsewhere? These are just some of the questions that Anežka Kuzmičová from the Faculty of Arts of Charles University, also recipient of last year’s Neuron Prize, will address in a five-year project that has just received funding from the European Research Council (ERC). "In our previous research, my team and I looked into how children experience fictional stories. Now we will focus on how they experience facts and nonfiction," says Kuzmičová, who will thus continue her collaboration with Markéta Supa, expert on children's media experience from the Faculty of Social Sciences at Charles University, and other colleagues across disciplines.

Why did she decide to work on this particular subject? "Children's leisure reading about facts is overlooked in research, and those who prefer, say, encyclopaedias to other reading materials tend to fall outside accepted notions of being a reader - so we don't know much about them. Existing work on nonfiction examines acquired knowledge rather than experience. At the same time, the book market has seen a huge growth in children’s nonfiction in recent years. There is a direct link with the rise of the internet, where information is available in unlimited quantities. In response, nonfiction authors have begun experimenting with new genres that cater to these enormous information needs in ways other than the internet, offering for example deeper context or sheer visual beauty," says Kuzmičová.

"But in the ERC project we will go much further - our primary goal is to find out what it actually means when a child becomes personally invested in a topic, what it gives them in terms of pleasures and lived experiences. The main focus will be on books and reading, but we will look at this in relation to other ways of engaging with facts, such as conversation, free play or listening," says the researcher, who is concerned that nonfiction is often put on the back burner as something that doesn't "count" as reading, and is even frowned upon in literacy classes. "Yet factual information makes up the vast majority of what we read as adults, it’s how we navigate the world. So it is perfectly logical that many children want to read facts too, and that their experiences of nonfiction can be no less rich than those afforded, say, by Harry Potter," the researcher explains.

Anežka Kuzmičová works closely with Markéta Supa and others at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University.

More encyclopaedias in schools

The problem is that many children don't have access to nonfiction. "Unlike fiction, these books are missing from the curriculum and even parents often perceive that 'proper reading' means fictional stories. And even if parents do want to encourage the reading of nonfiction, a big limitation for them may be that they cannot afford it, because children’s nonfiction tends to be more expensive than other books," says Kuzmičová, stressing that although this is primarily a project of fundamental research, the ambition is to provide insights for practice. "For example, our data will show how best to work with nonfiction in formal education. In the longer term, I hope that we will contribute to a more general shift in how reading overall is understood, and that even those who indulge in encyclopaedias, stock exchange tables or guideline documents will be acknowledged in their reader identities and specific affective competences. Such a shift is needed in literacy internationally, differences between countries are relatively small in this regard, which is also why I decided to seek an international mandate for my idea," shares the researcher.

Children will again be co-creators of research

Anežka Kuzmičová and Markéta Supa's research is remarkable in that it examines lived experience from children’s own perspectives. Such work requires creative props and methodologies and the upcoming project will be no exception. "We are currently looking at data from a smaller project where we did in-depth interviews with kids, at home and in children's homes. For example, the children made collages of real-world topics they were interested in and then told us more about them. This work will give us a great start and help us come up with the best possible props for the big project," the researcher says, adding: "It is incredibly encouraging that the ERC has decided to fund research based on a participatory approach, where children are given quite a lot of autonomy and decision-making roles - they are actually co-creators of the research process, which is still not fully respected in some research communities. In addition, in this project, we will include parents and authors, bringing together the perspectives of all three main groups involved in the circulation of nonfiction."

The fieldwork with children will have a purely Czech focus so that data can be easily linked and the cultural context is not lost. However, the aim is to create a model for work elsewhere. "International transferability was one of the most frequent questions during the evaluation interview. Of course, it would be nice to include children from more than one country, but this is beyond our means financially and also with regard to the linguistic sensitivity of the methodology and research ethics more generally," says Kuzmičová. Children living in Czechia, however, are in various ways representative of young readers in Europe, judging from international surveys such as PIRLS. There are also two favourable specifics. Firstly, our country has a large book market for its population, and secondly, Czech schools rely relatively heavily on textbooks, so children are familiar with traditional expository writing and will have a fairly good sense of what is different about leisure nonfiction.

British inspiration

The ERC recognises innovative, 'out of the box' projects that have the potential to significantly advance our knowledge - what was the inspiration for this one? "The biggest source of inspiration were of course children who are interested in facts. I have two such kids at home and I have repeatedly come across the topic of nonfiction in my previous work. There were always groups of children who read encyclopaedias when they had the choice, or footballer biographies, and who described their experiences no less vividly than those who preferred fiction," says Kuzmičová, for whom her international research experience has been formative.

"I studied and worked abroad for nearly a decade and a half, mainly in Scandinavia, but nothing changed my life and my thinking as radically as my two years in England, where, by the way, there are plenty of football books at every turn. England taught me a great many things, including that for good research it is not enough to have a neat idea and a sophisticated methodology, but that it is absolutely essential to keep seeing in front of me the specific groups that will be helped."

She was awarded the Neuron Prize for Promising Scientists in the Social Sciences last year.

It was surprisingly nice

But for a successful ERC project, it is not enough to have a brilliant idea. Formal preparations are just as important - how did they go? "First of all, I cannot stress enough the help of Martin Pehal, Vice Dean for Project Management and Grants at the Faculty of Arts, who got me support from outside the faculty and organised my mock interview and was my biggest fan. The Expert Group for Supporting Applicants in ERC Calls, which operates nationally in Czechia, also gave me useful comments. My closest collaborator, Markéta Supa, helped me remain focused toward the end. Markéta is a great optimist compared to me. Together, we also went through answers to some of the possible questions on my list," shares Anežka Kuzmičová.

"And many others pitched in, close colleagues and friends from all over the world. At times it was touching. I mostly didn’t want people to know that I’d made it to the second round, but some previous ERC holders heard anyway - I still have no idea how - and rang me up to offer advice which proved incredibly helpful," recalls the researcher, who admits that the preparation period was quite challenging for her. "For example, someone told me they’d rehearsed every day for their interview. I couldn't do this because I was immersed in fieldwork during those months, which I simply couldn't postpone," says Kuzmičová, adding with a smile that the interview itself was actually quite different from what she had imagined.

"I was surprised at how nice it felt. No one had described such experiences to me, rather I heard from people that the interview can be intimidating, that panel members can be tired," says the fresh ERC grantee, who was pleased by the interest of the evaluation panel. "Sure, they asked challenging, critical questions, but there was a collegial spirit. I sensed a genuine interest in my research. During the interview, one of the panel members made everybody chuckle when he said that I had cleverly designed a project on the joys of what most of us do most of the day - and what everyone would like their children to find pleasure in as well," says Anežka Kuzmičová.

| Anežka Kuzmičová, Ph.D. |

| She studied languages and literature at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University, and received her PhD in 2013 from Stockholm University, where she then continued as a postdoctoral fellow. In addition, she has worked in England, Denmark or Canada. In her interdisciplinary research on reading, she has collaborated with colleagues from over fifteen countries and countless disciplines ranging from pedagogy to neuroscience, mostly as lead author on joint publications. Since 2020, she has worked at the Faculty of Arts, CU, where she leads the cross-faculty Integrating Text & Literacy Research group, established thanks to a Primus grant from the university. She works closely with Markéta Supa and others at the Faculty of Social Sciences, Charles University. Last year she was awarded the Neuron Prize for Promising Scientists in the Social Sciences. |